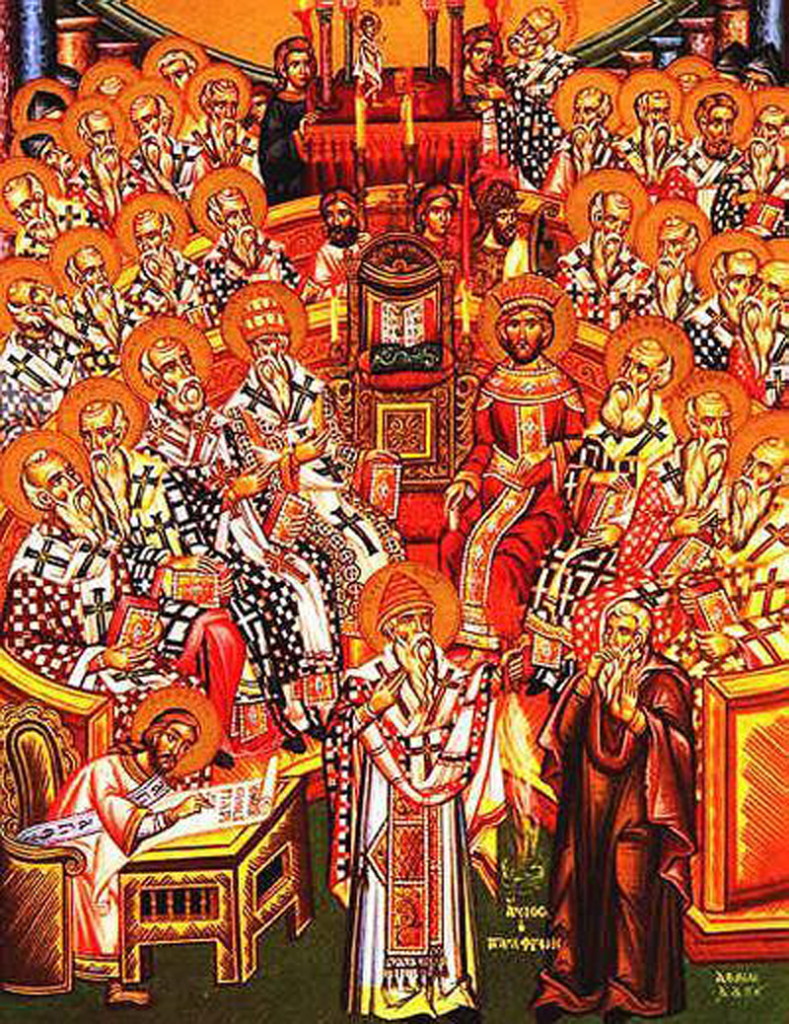

One thing that makes disputes about the Trinity intractable is the fact that different Christians have different views about just where authoritative Christian tradition is to be found. For Roman Catholics and the Eastern Orthodox, the Church, the organization run by bishops, is the earthly font of authoritative teaching. It is the Church, they argue, which gave us the Bible, and which has always taught us how to interpret it. In contrast, for Protestants (at least in theory and in rhetoric) the Bible alone is authoritative, and other traditions are to be accepted or rejected as they fit or misfit the teachings and practices mandated by the Bible. In practice, though, many Protestant theologians consider the decisions of the ancient “ecumenical” councils (the first seven recognized by Catholic and Orthodox traditions) to be inviolable. One suspects that Protestant reliance on the Bible hides a deeper disagreement about it. Is our New Testament, only first fully assembled, so far as we know, in the fourth century, authoritative because the bishops, or more widely, mainstream tradition told us that it is? Or is it authoritative because, and only to the extent that it represents the teaching of Jesus and his apostles, and those in their circles?

About the Trinity, matters can be clarified using an inconsistent triad of claims. By “the Trinity” here we mean whatever the traditional sentences are supposed to teach, imagining for the moment that there is such a determinate set of claims.

- The Trinity is taught by authoritative tradition.

- The Bible is the only authoritative tradition.

- The Bible doesn’t teach the Trinity.

Which should you deny? On the face of it, the one which you have the least reason to believe. Orthodox Christians and Catholics: deny 2, affirming 1 and (generally) 3. Protestants: deny 3, affirming 1 and (generally) 2. Christians who hold to a unitarian theology affirm 2 and 3, and deny 1. But who is correct? We know that only one can be, as 1-3 are an inconsistent triad; from the truth of any two of them, it follows that the remaining one is false.

A triune god is taught by official council statements, arguably starting with the second council, the one at Constantinople (381). It’s clearer in later ones, such as Constantinople II (533), which pronounces an anathema on “anyone [who] will not confess that the Father, Son, and holy Spirit have one nature or substance, that they have one power and authority, that there is a consubstantial Trinity, one Deity to be adored in three subsistences or persons” (Tanner 114) And Constantinople IV (869-70), recognized by Catholics but not by the Orthodox, confesses “belief in one God, in three persons consubstantial.” (Tanner 160) By the time of the Catholic Lateran IV council (1215), the older confession of the Father as the one God has given way to the confession of “only one true God… Father, Son, and holy Spirit… [the] holy Trinity…” (Tanner 231) These assemblies of bishops teach trinitarian theology. But are the all authoritative (Catholic), or only the first two (Orthodox), or none of them as such, but only if and to the extent that they’re expressing biblical teaching (Protestant).

A triune god is taught by official council statements, arguably starting with the second council, the one at Constantinople (381). It’s clearer in later ones, such as Constantinople II (533), which pronounces an anathema on “anyone [who] will not confess that the Father, Son, and holy Spirit have one nature or substance, that they have one power and authority, that there is a consubstantial Trinity, one Deity to be adored in three subsistences or persons” (Tanner 114) And Constantinople IV (869-70), recognized by Catholics but not by the Orthodox, confesses “belief in one God, in three persons consubstantial.” (Tanner 160) By the time of the Catholic Lateran IV council (1215), the older confession of the Father as the one God has given way to the confession of “only one true God… Father, Son, and holy Spirit… [the] holy Trinity…” (Tanner 231) These assemblies of bishops teach trinitarian theology. But are the all authoritative (Catholic), or only the first two (Orthodox), or none of them as such, but only if and to the extent that they’re expressing biblical teaching (Protestant).

Whatever we say about 1, what shall we say about 3? It depends on what it takes for the Bible to “teach” a doctrine. Does the Bible explicitly assert the Trinity? Absolutely not. There’s no term in the Bible which the author meant to refer to a tripersonal deity, to a truine god. And the idea of three hypostaseis or “Persons” sharing a common ousia (“essence”) just doesn’t belong to first century Christian thought. As best we can tell, no one in that century explicitly asserted such a teaching.

But theologically educated Protestants readily admit this. While they concede that the term “Trinity” isn’t in the Bible, they urge that the idea of it is. Some argue that various pre-Christian, extrabiblical, Jewish sources believed in some sort of plurality in or around or involving God. But of course, not just any plurality will do; multiple divine properties, actions, manifestations, or lesser divine servants will not support or provide any real parallel with Trinity doctrines. Others hint-hunt in the Old Testament. Isn’t God called “Holy” three times? (Isaiah 6:3; Revelation 4:8) Doesn’t God appear as there (human) persons to Abraham? (Genesis 18) Doesn’t the Bible speak of two who are called “Yahweh”? (Genesis 19:24) And isn’t this “angel of Yahweh” in fact the pre-human Jesus? (e.g. Judges 2:1) Frankly, zealous trinitarians will tell you one thing, and sober commenters will tell you another. Reader beware. The hint-hunters generally disregard the thousands of singular pronouns and verbs applied to Yahweh all over the Old Testament.

Correctly, most Protestant scholars who think that the Bible teaches the Trinity focus on the New Testament. The alleged hints simply did not suffice for anyone to “get it” in B.C. times. If the Trinity is revealed anywhere in the Bible, surely it must be in the New Testament writings written in the wake of Jesus’s life, ministry, death, resurrection, and exaltation.

But is it?

Yes. Indeed, the Trinity was revealed in the NT. Jesus himself speaks God’s words (John 3:24). Jesus said that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are God’s one name (Matthew 28:19). Therefore, God’s inspired words itself tells us that God is a Trinity.

However, we do not need to dismiss the fact that a plethora of OT passages points to the Trinity. How do we know this? It is by interpreting the OT through the NT since the latter is the fulfillment of the former.

Comments are closed.