For a few of the most serious and clever among us, mystery-mongering dies hard. They will stubbornly resist my previous attack on positive mysterianism about the Trinity, kicking back hard.

For a few of the most serious and clever among us, mystery-mongering dies hard. They will stubbornly resist my previous attack on positive mysterianism about the Trinity, kicking back hard.

I knew all along that the Trinity was going to be mysterious. And so now that I’ve discovered one way in which it is mysterious, well, I do celebrate it. You can rub my face in the apparent contradictions all you want, but it smells just fine to me. I celebrate the mystery of God; I don’t try to explain it away. You want to know: in the New Testament, is Jesus numerically identical with his Father, or are they numerically distinct? The scriptural answer is: yes! I mean, yes to both. Not my fault if you don’t like the scriptural answer.

What this last part ignores is that it is uncharitable to any author, human or divine, to attribute a contradiction to him. Incoherent readings of a text should be a last resort, and the less likely we think it is that an author is confused, the more reluctant we should be to attribute a contradiction to him. We must be sure we’ve really discovered “the scriptural answer,” rather than foisting our own confusion onto the text.

Some will reply that because God is so great, God will have to speak in apparently contradictory ways, if he’s to self-reveal to any significant degree.

Any theist, of course, thinks that God is too great to be fully understood by humans. But it is by no means obvious that if God self-reveals, God will be forced into saying apparently contradictory things to humans. The idea is that our conceptual scheme is too crude; we’re unable to make certain distinctions, and if we made them, then pairs of statements like “It is not the case that Jesus just is the Father” and “Jesus just is the Father” would turn out to be consistent with one another after all.

But for all we know, God has purposely avoided overwhelming us with information about him, revealing only what will seem coherent to our limited minds, like a parent who explains to his toddler that babies are made when “Mommies and daddies love each other very much and kiss and snuggle.” Witnessing sexual intercourse, or having it described to him in detail may well overwhelm the little tot, both emotionally and conceptually. (“Daddy’s hurting mommy… but he’s not!”) Thus, he gets the kiddie-explanation, and it’s good enough for the time being.

But for all we know, God has purposely avoided overwhelming us with information about him, revealing only what will seem coherent to our limited minds, like a parent who explains to his toddler that babies are made when “Mommies and daddies love each other very much and kiss and snuggle.” Witnessing sexual intercourse, or having it described to him in detail may well overwhelm the little tot, both emotionally and conceptually. (“Daddy’s hurting mommy… but he’s not!”) Thus, he gets the kiddie-explanation, and it’s good enough for the time being.

Some will object that surely God loves to humble us. He assaults our pride by revealing what can’t be understood, forcing us to trust in him, and to walk away from the demands of our sinful, damaged minds.

I reply that inevitably, with things as they are, there will be plenty of God’s actions and omissions that “can’t be understood” in the sense that we can’t explain them, because we don’t know or even can’t grasp some of his relevant motives. The child doesn’t understand much of what the parents do and say. But revealing what can’t be understood in the sense of telling the child something which for all the child can tell is incoherent… that seems rather cruel, and so seems wrong. I’d like the mysterian to tell us just where scripture tells us that God actually does this, and it seems like something a perfect being wouldn’t do. (And no, Isaiah 55:8-9 will not do; it does not say that.)

“OK, never mind why,” the mysterian may reply. “Perhaps we can’t know God’s motives here. But in fact, God has revealed paradoxes to us.”

But this just ignores that for every single paradox which the mysterian claims that the texts force on us, other Christians – serious, dedicated, honest, well-trained, and fully informed ones – think those texts admit of various non-paradoxical (i.e. seemingly coherent) readings. These will enjoy a great advantage over the mysterian’s apparently incoherent reading, which is that they don’t strongly appear to be false! Of course, there’s no simple formula for discovering the best interpretation of a text, and it is conceivable that we’re forced to a seemingly incoherent reading.

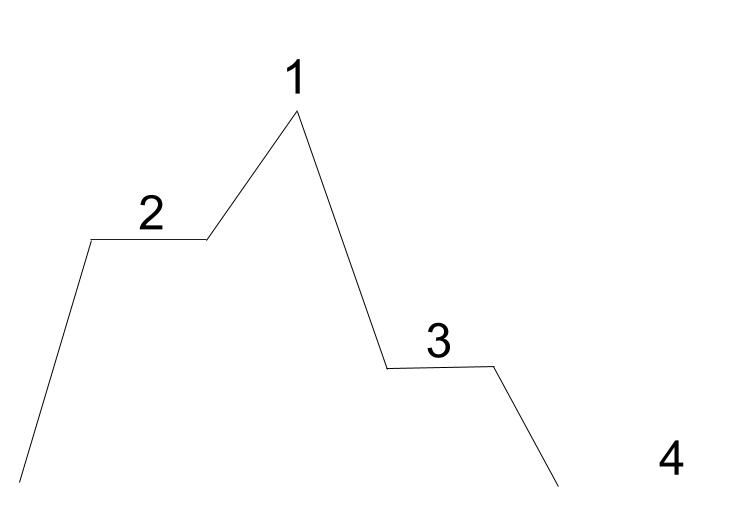

My parting shot against positive mysterianism takes the form of simply pointing out what it takes, practically speaking, to be a mysterian. Positive mysterians ought to consider how their views work in practice. Consider any the paradox or mystery of the form P and not-P. At any point in your thought life, you’re in one of four mental positions, when it comes to this particular paradox.

- thinking that P and thinking that not-P – (This is the stance the mysterian thinks God demands of you.)

- thinking that P (and not thinking that not-P)

- thinking that not-P (and not thinking that P)

- not thinking that P and not thinking that not-P (Either you’re thinking about something else, or you’re not thinking at all.)

Position 1 is a difficult trick. Some can do it, but it is unnatural, and it hurts. Soon, one half gives out, and one slides back down to 2 or 3. But if you arrive at 2 or 3, you’re disobeying God’s demands. Thus, you must push back up to 1. But it’s too hard to stay there. Repeat a few times, and you’re exhausted. You must retreat to 4, and spend most of your time there.

Many, taught mysterian theology, will simply camp out at 4, hardly ever trying to climb. But the theologically-inclined will choose to think about God. Getting up a head of steam, they ascend to 1. But every time, they soon find themselves back on 2 or 3. But 2 or 3 are an embarrassing place to be. 2 and 3 go against each other, and each goes against 1; standing at either 2 or 3 is a double failure. Eventually, one slides back down to 4.

Self-deception is an option now. Actively assure yourself that you’re at 1 (that’s where you mean to be, after all) though you are in fact almost always at either 2 or 3. But this too is hard for most to maintain. Thinking as a mysterian, then, is painful and ever-shifting, and always tends to poop out in defeat, settling into 4.

What about believing? There are four parallel positions, which we can represent like this, using “B:__” for “believing that __”.

- B:P and B:not-P

- B:P (and not-B:not-P)

- B:not-P (and not-B:P)

- not-B:P and not-B:not-P

But the case of believing is interestingly different. Unlike thinking, believing is not directly voluntary; one’s beliefs are determined by one’s perceived evidence. So long as the evidence seems both strong and evenly balanced, one will believe that P and not-P. But this strongly seems false, as it seems to be a contradiction, and it seems that all contradictions are false! Something must give. Soon, one’s belief is pushed out of 1, down to either 2 or 3. Here’s the interesting thing. Given that you have significant evidence, you will have a settled belief about this subject, even when you’re not actively thinking about it. 4 is not an option for the theologically tutored. But 1 can’t be sustained for long. So generally, your belief will be at 2 or 3. Which? One may alternate. But at any given time, one will find oneself whichever generally seems to have the stronger evidence. And that may shift depending on which scripture you’re reading at the moment, or what you’re thinking about then.

Speaking is different than believing and thinking, and speaking can hide these mental agonies from others. A mysterian can put up a good front, consistently saying both P and not-P. Granted, this will sound ridiculous to many Christians, and she may not be able to get away with it in some Christian settings, depending on just what P is. But at least in the mysterian crowd, she can consistently say P and not-P, thereby displaying her (apparent) obedience to the Word of God, which (she thinks) demands the paradoxical belief. But her speech most often masks that her belief-state is 2 or 3, with her thoughts cycling through all of 1-4, as described above.

This is what you sign up for, if you decide to be a mysterian about the Trinity. In brief, your mind has nowhere to rest.

What’s the alternative? One breaks out of these agonies by re-examining the matter until one’s view of the evidence shifts, making either P or not-P stand out as the true one; then, you deny the other. In this way, speaking, believing, and thinking are restored to unity, and the mountain shrinks down to a friendly plain. The mysterian will tell you that this can’t or shouldn’t happen, but a great number of Christians will tell you that to the contrary, the plain is quite nice.

My take on this is that a paradox cannot be truly believed, only asserted.

We have been conditioned to believe in the Trinity because it is what everyone else says, and extremely few people ever take the time to look into it or even think much about it. Nobody would believe me if I said I had a pet that was 100% goldfish and 100% parrot. But Christians have been taught to assert something similar without giving it much thought.

Another reason I say this is that the Trinity has not been, and cannot be, defended intellectually. The argument for it is that we can never understand it, but it just “is.” What other area of life would we accept such an argument? Basically, the argument is to stop arguing and get with the program. That doesn’t indicate any confidence in the actual belief, but a means of pressuring others to assert the same thing so as not to feel silly.

do you understand the god existing in 3 different modes argument?

Hi Dale. I’ve just had a look at your “Challenge” argument. I’d like to comment on the first premise: “God and Jesus differ.” You need to clarify this statement. If they differ, then you should be able to say how they differ. Do you mean: “God and Jesus are different beings” or “God and Jesus are different persons” or something else? For my part, I would deny that God and Jesus are different beings. Your fourth premise, “For any x and y, x and y are the same god only if x and y are not two,” only follows if x and y each denote some being.

That said, I agree with you that mysterianism is a totally inadequate defense of the Trinity. If Christians insist that the doctrine of the Trinity is an essential dogma of faith, then they should be able to say what it is that they believe in. On that point, I believe you are entirely correct.

Torley;

I would simply reply that if you are a different being you are also a different person. Unless you are going to redefine person or being. That, I believe is the language of the Bible. Hebrews 1.3 ” He is the ‘carakter’ of his being. A copy, an imprint, of his being, not the being himself. ‘Homoousios’,(same substance) would be a Greek term that was used later to try and define the oneness between Christ and God.’Heteroousios’, (another being) would be more appropriate in describing the relationship between the Father and the Son. Or even Homoiousios, (like substance). I could accept these definitions for I see them falling within the parameters as set forth in the Bible. But really I do not need to go outside the Bible to find simple terms that describe a distinction between the Father and Son. i.e. Son, Father, Messiah, Only true God;

mediator, my God (used by Jesus) etc. 1 Peter 1.3 says, “Praised be the God and Father of our Lord Christ Jesus.” Also Rom. 15.6

dokimazo,

I would agree that if you are a different being then you are a different person. However, the converse does not hold.

Regarding Hebrews 1:3, you might like to read what the Pulpit Commentary says about the passage you quote, here: http://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/hebrews/1.htm (scroll down to verse 3, which it translates as “express Image of his substance.” An image is of course distinct from what it is an image of, but the question is: distinct in what manner? Scripture itself answers this question when it speaks of the Son as the Word of God. (Hebrews 1:3 also speaks of Him as sustaining all things by His powerful Word – something He could only do if He were God.) A word or thought is distinct from the mind it proceeds from, but it is not a distinct being in its own right.

Finally, it is Christian doctrine that there is a distinction between God the Father and God the Son, but distinction does not imply that they are separate beings.

Torley;

Good comment. I have the pulpit commentary. It’s interesting that the Greek word used for ‘word’ is not Logos but remati. Perhaps jumping a little to fast. Who is the, ‘he’ mentioned in vs. 3? It is by his word (remati) that he sustains all things. I have no problem with him sustaining all things. He does not have to be God if he was given the authority to do so. Matt. 28.18 Also note the conclusion of the verse, “That he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty in lofty places. He was not the ‘Majesty’ but he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty. He had an assignment, he accomplished that assignment and he the sat down at the right hand of the Majesty. The point still remains. He was not the being (Trinity or God) that he was an image of. When we speak of the logos in context, it is a separate being even though some Unitarians may disagree with me on this point. They would agree with you to some point but then quickly define it as the spoken word of the Creator. I guess that is, a good question you raise, ‘distinct in what manner? I do not see that this distinction that is brought forth carries any weight in regard to Trinitarian or binarian viewpoint.

Hi dokimazo,

I’m impressed with your knowledge of Greek. I hadn’t realized that the Greek term for “word” in Hebrews 1:3 is “remati,” not “logos.” Re your objection that the image of God cannot be God, I would reply that the Son is the image of God “in Himself” (i.e. the Father), and is only called God because He is inseparable from the Father, as God’s understanding [or idea] of Himself is inseparable from God’s Mind. Ditto for the Holy Spirit (God’s love of Himself). (I might also add that God’s love is inseparable from His understanding.) Thus the Father occupies a pre-eminent role in the Trinity, as the Ultimate Source from which the Son and the Spirit (God’s understanding and love of Himself) are generated. That’s about all I can say, really.

Great points Dale.

Speaking of Mystery in terms of Gods essence or ontologically, I do believe there will be mystery due to the fact that even in the final state- we will never know God as God knows himself. Because of this gap, there will always be a sense of mystery pertaining to God even when in a direct, non-mediated relatioship.

Comments are closed.