|

Listen to this post:

|

Charismatic Calvinist Sam Storms, in a post at the Parchment and Pen blog:

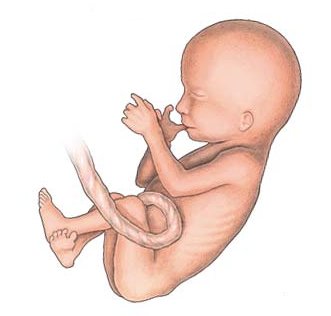

Conception: God became a fertilized egg! An embryo. A fetus. God kicked Mary from within her womb!

Birth: God entered the world as a baby, amid the stench of manure and cobwebs and prickly hay in a stable. Mary cradled the Creator in her arms. “I never imagined God would look like that,” she says to herself.

…Some are bothered when I speak of Jesus like this. They think it is irreverent and shocking!

But his purpose is not to shock, but to amaze.

The Word became flesh! Amazing! Merry Christmas!

It certainly is shocking and amazing, this claim that God (or a divine person within God) became a man. But why?

- Not just because it is unusual. (It certainly is – I haven’t met any human claiming to be a god, although claims like this are found in various religions.)

- Not just because it involves a miracle (i.e. the miraculous conception of Jesus without a human father).

- Not just because it involves a change in God (i.e. not being human, to being human).

- Not just because it involves God having surprising qualities.

No, the reason the claim shocks is that it seems incoherent, and for that reason, it seems false. But it takes some effort to see this. Storms simply bombards us with claims that sound surprising. e.g.

…the invisible became visible!

the untouchable became touchable!

…the unlimited became limited! the infinite became finite!

the immutable became mutable!

…spirit became matter!

…the almighty became weak!

He wishes to produce amazement, but not disbelief (which would result from straightforwardly asserting one of the contradiction lying nearby). Thus, the reader is left to discern – and be amazed by – the contradiction which is always just out of view.

Take the last one – the omnipotent God becomes a weak fetus or baby. That’s just a change – no contradiction there. But, most careful, reflective Christian theists think that God is essentially omnipotent. It is a contradiction to say that a being which is essentially omnipotent became weak, for what is to any degree weak is not omnipotent. Again, the ancient, classical view of God has him being essentially immutable – not something which happens to be immutable, but might have been mutable. It is a contradiction to say that something which is essentially immutable changes.

I humbly suggest that we ought not indulge in amazement that a contradiction is true, for we all know that no contradiction can be true. No, not even on Christmas.

There are orthodox/catholic theories which attempt to solve these problems – kenosis theory in particular, and unitarian Christians have their own solutions. But apparently “Reclaiming the Mind” is put on hold this time of year. Kenosis theory, as developed by recent Christian philosophers, holds that what are usually thought of as essential divine features – e.g. omnipotence, omniscience – are not essential to a divine being after all. Thus, the divine Word can at least temporarily be, e.g. to some degree ignorant and weak.

Interestingly, this move – demoting a traditional divine attribute from essential to non-essential doesn’t work in the case of immutability. The concept of any being changing from being immutable (unchangeable) to being mutable (changeable) is a contradiction – even if at the start it was only contingently (non-essentially) immutable. It looks like if something’s unchangeable, it must be essentially unchangeable. (Don’t get it? Suppose that a thing changes from being unchangeable to being changeable. That’s a change, right? So, it wasn’t, at the start, unchangeable. And yet, we stipulated that it was. The scenario as a whole is contradictory.)

This is why sophisticated contemporary proponents of kenosis theory like Stephen T. Davis simply deny that God is immutable in the classical sense. In their view, God can and does change – not in his character, but in some of his other features. In patristic times, they would have dismissed this out of hand, but I think theists are on strong grounds to think that God changes in some respects. Any real response, any free action on God’s part, is going to involve him changing, is it not? e.g. His creating the cosmos from nothing. To many reflective Christians, trinitarian and unitarian, divine immutability seems dispensible.

But this is not true of several other divine attributes, ones which it seems Jesus could not have had. For instance, the man Jesus was tempted, but you can’t tempt God. Jesus died, but God is essentially immortal. Jesus is under a god, but God can’t be. If you think that Jesus is God, or that he is divine in the way the one God is divine, you should lay aside amazement and try to deal with the contradictions your christology seems to imply!

So this Christmas, do be amazed that God sent his one and only Son to redeem sinners like us. But, don’t be amazed that God makes contradictions true, ’cause he doesn’t. And if you agree that Jesus is the most important and interesting man in history, and indeed the unique Lord under the unique God, make it your project in this new year to find for yourself a consistent and biblical christology.

Pingback: trinities - God the baby – Rama / Ram, avatar of Vishnu (Dale)

Scott:

Here’s the problem: if God generated Jesus (in whatever way you care to name or define) then Jesus’ existence has a commencement in time, and he is not eternal, which means he cannot be deity.

If God did not generate Jesus in some way, then Jesus is not His son (unless by adoption, which both you and I deny).

Additionally, if you insist that Jesus can truly be called God’s Son on the basis of the fact that he is “the same type of being”, you must concede the Holy Spirit is also God’s Son, since “he” also meets that criterion.

This is yet another reason why the title of “Son” can only ever be an honorific when applied to the Trinitarian Jesus. It clearly does not refer to literal sonship, whether by procreation (e.g. Adam + Eve = Abel) or special creation (e.g. God created Adam, “the son of God”, as Luke refers to him in 3:38).

Well, this seems to be a case of special pleading. If there is no causal relation, there can be no sonship except by adoption – which again relegates Jesus’ sonship to a mere honorific.

Dale, thank you for your answers to my questions. I truly appreciate this!

I’m not a trained philosopher, so I will obviously not be able to properly articulate my objections. To me, experiencing something “at once” seems language that is inherently connected to a temporal context. (Just like “doing something”.) So I think God might say that this statement of yours just doesn’t make sense.

I understand divine timelessness entails that God himself lives in an eternity of time (since there is time.) God by necessity exists now.

Does this mean that you believe that by the act of creation, God may have changed from a timeless, unchanging condition (who “has its life all at once, with no flow”), into a temporal being? That seems to be an impossible possibility.

Isn’t this just an argument that for a temporal God foreknowledge and freedom would be incompatibile? And isn’t this exactly the kind of circular reasoning that Hasker employs?

And I believe Scripture makes clear that this is the case. To me, divine timelessnes isn’t equal to eternally foreknowing everything at all. Selective foreknowledge means that God can choose not to foreknow indiscriminately all the future acts of his creatures and God can, with all sincerity, respond to, and freely interact, with creatures.

I think we cannot truly understand timelessness. And so, we cannot truly say that divine timelessness entails that God cannot change (do things) within a temporal context/be a historical God, knowing which moment is nowfor all of us creatures whom he has set in the stream of time. (Which, by the way, is actually relative, as time appears to slow down when it is exposed to gravity.)

This is crucial to me. Do you say that God kind of “caused” Jesus being pierced through and being betrayed by some intimate acquaintance, because he was the one who ‘made it inevitable.’ He ‘set it up’? Did Judas act freely?

There is a big difference between foreknowing specific things will happen (with no injustice and no violation of man’s free moral agency) and setting things up/making them inevitable. (Compare Job 34:10-12.) I believe that at the time Jesus selected his 12 apostles, Judas’ heart presented no definite evidence of a treasonous attitude. Otherwise there would have been inconsistency in God’s direction and guidance, which would make him, according to 1Ti 5:22, a sharer in the sins that Judas committed. Judas allowed a ‘poisonous root to spring up’ and defile him, (Heb 12:14, 15) resulting in his deviation. Next, it was the Devil, not God’s direction, leading him in a course of thievery and treachery. (Joh 13:2; Ac 1:24, 25; Jas 1:14, 15)

To me it seems that Scripture shows that God is able to foreknow certain things without predestinating or foreordaining them. This is one of the major reasons why I believe God must be timeless.

Logically, there should be no conflict between God’s foreknowledge (as well as his foreordaining) and the free moral agency of his intelligent creatures. But any understanding of God’s use of the powers of foreknowledge and foreordination must also harmonize with God’s own moral standards and qualities, including his justice, honesty, impartiality, love, mercy, and kindness.

Yes, I am. Yet, I disagree with open theists about the incompatibility of libertarian free will and divine timelessness. Or, rather, I disagree with certain assumptions about divine timelessness.

This statement only makes sense within a temporal context and as such is not related to divine timelessness. It’s not been true that I will lie tomorrow. But it evidently will or will not be true. Nevertheless, God will not know what I will freely do tomorrow. Like he doesn’t (cannot) lie. (Titus 1:2)

It’s a fascinating and difficult subject, and I have more reading and thinking to do. Thank you for your help.

In a sense, yes. It’s existing, and being such that no temporal predicate applies to one. A timeless being has its life “all at once”, with no flow. It doesn’t exist “at” any time, past, present, or future. Thus, it would have to be unchangeable – because change presupposes a before and an after. This is all clear enough from early medieval philosophy. My view is that nothing that exists can be like this given that there is time. Time isn’t the sort of thing anything can be “outside of”. It may be, though, that if God hadn’t created, there would be not time, yet God would nonetheless exist in a timeless, unchanging condition. At least, I don’t see any way to rule this out.

For the above reason, I wouldn’t quite say that God is “exclusively temporal”. But I think there are good arguments for the incompatibility of foreknowledge and freedom. In brief, the past can’t be changed. But some past fact logically entails that you’ll, say, tell a lie tomorrow. Thus, that lie-telling too is unchangeable – it’s logically implied by something which is. Thus, it’s unavoidable – right now, you *will* do that, and given the past, there’s no chance that you won’t. And yes, I think Hasker’s arguments are plausible – see his book for the whole story.

If I understand the question, yes. A historical God must respond to, freely interact act with creatures. Compare: Moses’s arguments with God.

Yes – an omnipotent and omniscient being can infallibly foreknow any fact which he makes inevitable. Facts like those, circa 500 BCE, could have set up to possibly play out in umpteen different ways.

Helez, you’re actually a sort of open theist despite yourself, because you believe that God lacks what is called “comprehensive foreknowledge”. See pp. 1-6, and footnote 17 here. In my view, it’s not enough to say that one’s future action isn’t foreknown. It’s simply being inevitable is the problem, and if God could but chooses not to know this truth, we have the same problem as above. (It’s been true that you’ll lie tomorrow. That this is so, implies that you’ll lie tomorrow. It’s impossible to change any past fact. Ergo, it’s inevitable that you’ll lie tomorrow. Therefore, there is no option open to you of not lying tomorrow, therefore your lie will not be free.)

@Dave. This takes us deep into metaphysics and the like, and I don’t think this comment area is the best way to address it; or at least, for me to address it. Suffice it to say, your response doesn’t convince me. E.g., in the case of God, I wouldn’t expect ‘procreation’ to be entirely like material generation of a creature. Since it’s supposedly an immaterial generation, I’d expect things to be different. One might think along the lines of an asymmetrical ontological dependence relation, and no causal relation whatsoever. In this case, no temporal sequence is required (contra Arius).

Indeed. God is called a Father because he is the Creator. Jesus is called God’s Son for the same reasons angels and even the man Adam are called sons of God. (Job 1:6; Luke 3:38)

Scott,

I am familiar with this argument, but it fails to satisfy.

You are human because you were physically procreated by humans, and you are your father’s son by virtue of your procreation.

But the Trinitarian Christ cannot be “Son” by virtue of his procreation, since this would imply he has not always existed (a la Arius). Nor is he “Son” by virtue of his Father’s nature, since this would imply that his deity is derived from the Father (a la Justin Martyr).

You are your father’s son because he is responsible for bringing you into the world, which is what fatherhood naturally entails (note that Adam was also God’s son in this way), and you share your father’s nature because you are his son (not the other way around). But this cannot be said of the Trinitarian Christ, and thus your analogy breaks down.

It is not enough to say that the Trinitarian Jesus is “Son” because he is the same type of being, since this is not what the word “son” means. Using that logic, I could call you my son because we are “the same type of being.”

The Trinitarian application of “Son” to Christ can only ever be honorific, since it is not in any way equivalent to any process or relationship to which the basic meaning of the word “son” corresponds.

Whoops– that’s “@Dave”

@Dale. This is half true. For Trinitarians, the second person’s being ‘the Son’ implies being the same kind of being (divine). Just as my own father is human, so too am I human. But you are right to suggest(?) that ‘being generated’ doesn’t express (all of) what the Son’s essential powers are.

Most Trinitarians, if they respect the catholic tradition (e.g., Origen, Hilary of Poitiers, Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine), say that the second person is eternally generated by the Father.

So, I don’t think Arius and Trinitarians are in the same boat here (and one might say, ‘obviously’ given the Nicene Creed in 325 and Constantinople in 381).

Scott:

Interestingly, this is equally true of Trinitarnianism.

@Dale: Whether or not Arius had a concept of libertarian free will, etc., there’s a more general point that I was raising. Namely, for Arius, this super-awesome first creature is only called ‘Son’ because ‘God’ knows that this creature will do great stuff when incarnate in Jesus Christ. This illustrates just how different Arius is from tri-theism. It’s only ‘God’s’ foreknowledge of what this creature will do that God calls this creature His ‘Son’. The name ‘Son’ is merely an honorific title, and has nothing to do with what kind of being this creature is.

To avoid misunderstandings: I obviously agree that there’s a huge problem with the idea of God eternally foreknowing what we’ll freely do, but it cannot be the incompatibility of libertarian free will and divine timelessness. Harper only shows that his assumptions about divine timelessness are false/incompatibility with libertarian free will.

Besides, doing something in general only seems to makes sense within a temporal context.

Dale, do you think you understand divine timelessness? (As you seem to be quite confident about the necessity of God himself being exclusively temporal to be compatible with creatures having the gift of a genuine libertarian free will.) I do not.

Do you believe “the problem” is accurately explained by Hasker here? (–> http://www.opentheism.info/pages/information/hasker/incompatibility_timelessness.php), and the arguments advanced by him for the supposed incompatibility of libertarian free will and divine timelessness are actually sound???

Do you believe God’s timelessness would prevent him from being preeminently a historical God?

Another question: How do you think a temporal God could know that Jesus would be pierced through? (Isa 53:5; Zec 12:10; Mt 27:49; Joh 19:34) Or how could a temporal God know that some intimate acquaintance of Jesus would be his betrayer? (Ps 41:9; 55:12, 13; 109:8; Ac 1:16-20) Do you think God predestinated or foreordained such things? Or do you think a temporal God could predict these events with 100% certainty without foreordaining them?

I would be honored if you respond.

P.S. If, in certain respects, a timeless God chooses to exercise his infinite ability of foreknowledge in a selective way and to the degree that pleases him, who can rightly say to him: “What are you doing?” (Job 9:12; Isa 45:9; Da 4:35)

Right. Good point.

If the Son just is the divine nature, yes. But if the Son is a composite of the divine nature and something else, maybe not.

If the divine nature is just the essential properties of the Son, then one could say that his non-essential properties are changeable, while his essential ones are unchangeable. This, though, is almost a trivial point – everything’s essential features are unchangeable, so long as that thing exists. Of course, if the Son exists at all times, then so would his nature (essence).

Some theists, I think with good reason, hold that God is changeable, and in a sense “in time”. They point out that what’s important is that God’s character is unchangeable – he’s not a capricious god.

Hey Scott – your (1) and (2) are plausible, but I from what I remember in this period, when they ever did think about the compatibility of foreknowledge and freedom, they just said that God eternally foreknows what you’ll freely do – which is a way of just not seeing the problem. I don’t think this issue was a big one in Platonists’ minds – not sure why. But I’d expect someone like Arius to assume their compatibility, but not have any developed views about the means of God’s knowing this, or on how to defend the compatibility.

Hi Dale!

Thank you for helping me piece together what the early formulators of the Trinity believed regarding immutability. When someone says that God is immutable, does that apply only to the Divine Essense or to the persons also? The anathemas of Nicea affirm the immutability of the SON so it would appear that the Nicenes believed the Divine attributes apply to the entities of the F,S & HS and not just the Divine nature in itself. I accept that the Divine nature is immutable but does that prove the SON is immutable? The incarnation Doctrine doesn’t appear to allow it. The very act of assumption (to take to oneself) appears to me to entail change. why?According to logical procession of thought the SON never BEFORE the incarnation had a physical component, AFTERWARD he did. The SON now had parts subject to change. As an entity The Son changed BY assuming a second nature. He was not the same as he was before he assumed – hence the Incarnation necessitates these three attributes -Mutability, Complexity and Temporality. 3 attributes not considered identifiers of Deity in classic theism.

^^ BTW, thanks for explaining your rationale. I can see where you’re coming from, though I still don’t agree.

Scott, what’s your view on the knowledge/determinism question? Are you an open theist? A Calvinist? Something a little less exotic?

@Dave: Fair enough. I’m not *committed* to attributing to Arius some nascent version of Middle-Knowledge. How I got here was from such premises

1. Arius seems to think that the ‘Son’ could have done otherwise (= libertarian freedom) when incarnate in Jesus Christ.

2. Arius seems to think that ‘God’ knows what the ‘Son’ would freely do.

3. Arius seems to think that ‘God’s’ knowing what the ‘Son’ would freely do is the basis on which ‘God’ calls this person his ‘Son’–‘by anticipation’.

4. I recall that Clement of Alexandria endorses a version of libertarian freedom. So, this notion of freedom is not new, it was already in the air in Alexandria.

Scott,

Thanks for posting this. I’ll take a look and think it over. At first reading it doesn’t appear to suggest middle-knowledge. I presume your interpretation is based upon the following clause:

Arius says a number of things here, but none of them correspond to Molinism as far as I can see.

Yeah, I guess that’s true. But Arius was never criticised for his views on God’s knowledge (whatever those might have been). He was attacked exclusively for his Christology.

Dale said, “Maybe the idea is that it’s only intrinsic changes which are impossible. Then, the Logos would at that time enter a new relationship with a complete human nature. Intrinsically, it’d be unchanged, but it would have undergone a merely relational change.”

This is my view.

@Dave: Here is the passage from Arius’s _Thalia_ that could be read to be attributing Middle Knowledge to (the unchangeable) God (who becomes ‘Father’–ironically). Of course, there are other ways to read this; I found it an interesting interpretive possibility.

If one doesn’t like Middle Knowledge for philosophical reasons, and Arius seems to posit it, then you’ve got a nice ad hominem attack–‘if Arius likes Middle Knowledge, then you shouldn’t’. This is only a rhetorical point, of course.

Section 8 The Divinization of the Son

“By nature, as are all others, so the Word Himself is changeable,

And remains good by His own free will while He chooses;

When, however, He wills, He can change as we can,

Being of a changeable nature.

The Apostle writes, ‘Therefore God has highly exalted Him,

And given Him a Name which is above every name;

That in the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

Of things in heaven and things in earth and things under the earth.’

And David writes, ‘Therefore, God, your God, has anointed you

With the oil of gladness above your fellows.’

If He ‘therefore’ was exalted, received grace and was anointed,

Accordingly He received the reward of His will. But if he acted out of will, obviously

He is of a changeable nature.

Because indeed God also foreknew Him to be good,

For this reason He gave Him by anticipation

This glory which, as man, He afterwards

Attained from virtue; so from His works,

being foreknown.

God caused Him thus to come to be.

Christ then is not true God; but the Father

Has adopted Him as His own Son,

Engodding Him by participation through grace.”

To be more precise: I disagree with open theists about the incompatibility of libertarian free will and divine timelessness.

So, let’s say I’m something like an open theist, but not exactly… 🙂

Hi Dave, no, I believe God exercises His powers of foreknowledge selectively or discretionary (in contrast with open theism and predestinarianism). This is in harmony with God’s own righteous standards and is consistent with what he reveals of himself in his Word. It is not a question of ability, what God can foresee, foreknow, and foreordain, for “with God all things are possible.” (Mt 19:26) The question is what God sees fit to foresee, foreknow, and foreordain, for “everything that he delighted to do he has done.” (Ps 115:3)

Oho! Helez, are you an open theist?

Denying the prehuman existence of the person known as Jesus (a.k.a. “the beginning of the creation by God” -Rev 3:14) means that when the Bible says that all thing are created “through” and “for” Jesus, (Col 1:16; Heb 1:2) God must have created everything ‘with Jesus in mind,’ or something similar to that, i.e. God must have known in advance that it would be necessary for someone perfect like Jesus to play the sacrificial role in human history even before He actually started to create anything at all. Right? This is what I believe to be an unbiblical and gross misunderstanding of Jehovah God; who he is and what he is like. It would imply that God is at least partly responsible for all the evil and suffering in our earthly vale of tears.

(Some have such an arbitrary view of God’s perfection and powers. God’s almightiness really doesn’t conflict with God not foreknowing all future events and circumstances in full detail. All history from creation onward is much more than a mere rerun of what had already been foreseen and foreordained, as Biblical evidence shows.)

Peace to all.

Reposting this because I messed up the formatting… sorry about that.

Scott:

No, it’s entirely consistent with Arius’ personal Christology.

I don’t see this in Thalia. As Dale has observed, middle-knowledge was a much later concept. The Arians had a far more simplistic rationale.

OK, but I’m not sure how this is relevant to our discussion.

I agree Arius believed the Son to be originated. I agree Arius believed the Son was not true deity (though Arians were still comfortable applying “theos” to Christ). I agree Arius believed the Son was different in nature to the Father. None of this is under dispute, nor does it contradict the teaching that Jesus is God’s Son by virtue of his divine generation.

Thalia appears to indicate (and later Arian creeds confirm) that Jesus’ divine Sonship is predicated upon his mystical “generation” by the Father. It seems to me that the Arians saw no problem with the concept of God “begetting” a divine being whose essence was not identical to His own.

Yes, that’s his Platonic influences shining through. I don’t know how many Christians would accept Gregory’s argument today.

Immutability and impassibility were essential to neo-Platonic Christology, but this resulted in some awkward questions about Jesus’ incarnation and passion. Irenaeus’ response is quite refreshing; unable to resolve the dilemma, he boldly asserts a paradox, claiming that at the incarnation, the impassible became passible!

Scott:

No, it’s entirely consistent with Arius’ personal Christology.

Hey Scott,

I’m pretty sure that no one before Molina had a concept of Middle knowledge. I think you mean what’s usually called “simple foreknowledge” – as based on a perception or quasi-perception of the future (or of one’s own plan). Middle knowledge is only of subjunctive conditionals, of the form: If agent A were in circumstances C, A would freely do action S.]

On Arius – what’s at issue, really? He’s a subordinationist, right, who thinks that Jesus’ quasi-divine status is due to his being the first creation… He broadly similar to the late 2nd c. subordinationists (aka logos theologians), but more strongly emphasizes the inequality in greatness etc. between Jesus and God.

Hi reality checker,

Yes – it’s hard to see how the Incarnation, as traditionally understood, would not be a change. At some point in time, the Logos/Word – which is personally identical to the man Jesus – becomes human. Hard to see how an immutable being could gain a nature. Maybe the idea is that it’s only intrinsic changes which are impossible. Then, the Logos would at that time enter a new relationship with a complete human nature. Intrinsically, it’d be unchanged, but it would have undergone a merely relational change. But I believe as immutability was classically understood, it was supposed to rule out even relational changes – they thought of relations not of, as it were, hanging between the relata, but rather as amounting to each relatum having a contingent intrinsic property.

@Dave.

I take it that this Arian Creed diverges from some features of Arius’s own teaching. In the passage I’m thinking of from the Thalia, Arius says that God knows the great deeds that the ‘Son’ will freely do, and thereby honors him by calling him his ‘Son’. This is consistent with calling this first creature ‘the Son’ by adoption. The point is that the title ‘Son’ is an honorific title, and not one ‘by nature’.

Here’s some (long) passages from the Thalia (from Ford Lewis Battles reconstruction of the Thalia)–(again, the passage re: middle-knowledge is forthcoming–I happen to have this one in my computer). I cite this passage to show that the Son is _not_ the same in kind as God (the Father). Arius takes ‘to be unoriginated’ as the mark of deity. But the Son is originated. Therefore, the Son is not God. Therefore, the Father and Son are different in kind. Those who know Gregory of Nyssa know that he rejects ‘being unoriginated’ as the mark of deity, and replaces it with ‘being unchangeable’ such that the Father and Son are both unchangeable and therefore equally divine.

God Before All Creation:

“God was not always a Father, but once God was alone,

For the Word was not with Him.

Not yet was He a Father, but afterwards became a Father;

Understand that the Monad was, but the Dyad was not before it subsisted.”

The Creation of the Son:

“Not always was the Son, for He was not before His begetting.

The Father existed before the Son. Nor was He truly Son, from the Father.

For just as all things were born out of non-being,

So the Son of God, though from the Father,

Also came out of non-being.

There was a time when the Son was not;

For just as all things were created, made,

He, too, is something made, a creature.

Just as all things were not before, but came to be.

He also who was God’s Word, once was not,

And was not before He was begotten, but had a beginning of being.

Just as all things subsist by God’s will, not existing before,

So also He was made by the will of God, and did not exist before.

Not the proper Begotten One of the Father is the Word—

For each is different from the other—

But He has Himself come to be by grace.

Just as all being are foreign and unlike God in essence,

So too is the Word alien and unlike in all respects

To the essence and proper nature of God.

For the Son belongs to things begun, created, and happens to

Be one of these.

While the Father subsists, Unbegun:

Nothing proper to God in proper subsistence

Belongs to the Son, for they are not equals,

No, nor of the same essence.

The Son is God Only-Begotten: Each is different from the Other.

At God’s will the Son is all He is and has:

And when and since He was—from that time subsisting from God the Father.

Thus did the Unbegun make the Son a beginning of things begotten.

The essences of the Father and of the Son

And of the Holy Spirit are separate in nature,

Estranged, disconnected, alien, without participation

In each other; utterly unlike one another

In essence and glory unto infinity.

In likeness of glory and of essence, the Word

Is utterly diverse from both the Father and the Holy Spirit,

Thus is there a Triad, not of equal glories;

Not intermingling with one another are their subsistences;

Each one more glorious than the next below

In glory is, unto infinity.”

The Son’s Knowledge of the Father

“Full proof there is that God is invisible to all beings:

To things that are through the Son, and even to the Son Himself

Is the Father invisible. How can He who is from the Father

Know His own Begetter by comprehension?

For plain it is that that which has beginning

Cannot conceive how the Unbegun is, or grasp the idea thereof.

God, then subsists inexpressible to His Son:

For He is to Himself what He is—unspeakable.

Hence, impossible it is for the Son to investigate

The Father, Who is by Himself. Even know Himself

The Son cannot, for as Son, He really subsists

At the Father’s will. Fail in comprehension he must,

And cannot know—perfectly and exactly—

Or see His own Father. But what as Son He knows

And sees, He knows and sees according to His own measure,

And we too know and see according to our power.

How, then, does the Son see the Invisible?

By that power whereby God sees, and and in His measure

The Son endues to see the father, as is lawful.”

Scott, this question may turn upon differing translations (and interpretations?) of Thalia. The version available here mentions adoption, but does not define it explicitly. Yet the context seems to imply that the basis of the adoption is the Son’s unique generation by the Father.

The 6th Arian Creed of AD 351 seems more explicit:

According to this confession, Christ is God’s Son by virtue of the fact that he was begotten “before all ages”, while he is “God, Son of God” because he has his being directly from the Father.

I’ll get the exact passage from Ford Lewis Battle’s reconstruction of the Thalia (which is in my office) in due course. Arius explicitly says that the “Son” is an _honorific title_ in virtue of what God knows the “Son” will do when he lives a human life and dies on the cross.

@Dave: what’s the basis for the adoption? According to Arius, it is what God knows the “Son” will do. (I’ll get the exact passage from the Thalia once I return to my office next week.)

There are other ‘Arians’ who wouldn’t think this–e.g., some “semi-Arians” who proposed the “homoiousian” and interpreted it as sameness-in-kind. In which case, this is technically tri-theism with three persons (=three tropes of divinity) equal in kind. Of course, there were those who advocated the “homoousian” and interpreted it as sameness-in-kind. The likely difference between these position is whether there is one or three instances (tropes) of divinity.

This is how Arius expressed it in Thalia:

Under Arian Christology, Jesus’ sonship can therefore be interpreted as literal (hence “made”) or metaphorical (hence “adoption.” Either way, middle-knowledge is not in view.

@Helez: It would also run in the Arian family. It seems to me that Arius appealed to middle-knowledge (of Jesus’s future virtuous deeds) as the basis for why ‘God’ calls Jesus his ‘Son’.

I hope you will. 🙂 (Not one that requires a denial of his prehuman existence – for that would be unbiblical, or one that requires the belief that God exercised foreknowledge regarding how the person known as Jesus would be like and what would be his final destiny, even doing so before he came into existence, – because that would raise inherent contrarieties.)

Thanks anyway, I enjoyed your post.

Excellent observations Dale. Immutability, Simplicity, Atemporality all appear to have been threatened by the Incarnation. To counteract this threat the Nicene Fathers emphasized that the Divine nature remained immutable while the Son ‘assumed’ or took on a reified human nature. I believe most would agree that the person of the Son did himself begin a human existence. At one point he was God only, at the next point he was the God-man. To me this signals a change in existance of a person by adding a type of existing and that looks to me as patent mutability; since it happened in time – temporality; and since the reified human nature is also identified as the Son – non-simplicity. So questions come: Are the Divine persons Divine in their own right or only as joined to the Divine nature? what sustains personhood sans any nature? Since the Son became contingent when becoming human does this mean that part of the Son is contingent, part non-contingent? in other word does the Son have parts?… I’m a little dense – be gentle.

I indeed believe that Jesus was all time in heaven. Even while He was on the Earth is human body.

(Jn. 8:12) “… Jesus spoke to them, saying, “I am the light of the world…” and (Jn. 9:5) “While I am in the world, I am the light of the world.”

The light of the world (in modern terminology, electromagnetic waves or photons of the universe) are always on the heaven.

BTW, you can read about my christology at http://endofgospel.org/online/whatis.xhtml

I also should find time to write my teaching about God, gods, and trinity. Maybe in 2011. I am busy with other things.

Dale – your series when you first started this blog, through historical and contemporary theories of the Trinity, was extremely helpful and informative. I would be thrilled if you would consider educating us on theories of the incarnation in the same fashion. I made an attempt at something along these lines last Advent, but I don’t feel that I have understood things as well as I ought.

Thanks, Kenny – I will consider that. I’m actually teach a class on Incarnation theories in the Spring, but a lot of it is pre-20th c. Start in the Bible and work through the patristic debates, etc. There sure has been some interesting stuff by analytic philosophers in the last 30 years or so…

Merry Christmas!

(John 3:13) “No one has ascended into heaven, but he who descended out of heaven, the Son of Man, who is in heaven.”

Jesus says that He is on heaven during His life in flesh. So Jesus descended on the Earth but never was not in heaven.

His divine nature never changes, He is always on heaven.

Hi Victor,

Modern translations don’t have the phrase “who is in heaven” at the end, because the best manuscripts lack it. Happily, we can continue assuming that no contradiction is true.

Merry Christmas,

Dale

Comments are closed.