The next theory up to bat is by philosophers Mike Rea of Notre Dame and Jeff Brower of Purdue University. In some ways Mike reminds me of his mentor Al Plantinga – a tall guy you don’t want to argue against unless you absolutely have to. He’s published many articles in metaphysics and philosophy of religion, and is perhaps best known for this book. He’s presently editing several books, including one of recent essays on the Trinity, which I’m really looking forward to seeing. Jeff is one of the best medieval philosophy specialists around, focusing on metaphysics, philosophy of religion, and ethics. I think he has excellent tastes in medieval philosophers. Both of these guys are top-notch, and you’ll always learn a lot from anything they publish. Both of them, by the way, have many papers available to download from their websites, and their other Trinity work will surely be discussed here at some future date. The one I’ll be discussing in this series is here. Theirs is a bold and controversial theory, and one which is quite out of step with the Social Trinitarian views that have been so popular of late.

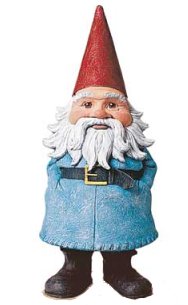

“Material Constitution and the Trinity” (Faith and Philosophy 22:1, Jan 2005, 57-76) is a difficult and technical article, dense with argument. Philosophers will appreciate how well it’s crafted; I not sure many others can get through it! Here I’ll just lay out the broad lines of it, getting slightly more precise in future installments. Consider Ned the gnome:

How many things are pictured here?

You might say just one – a gnome statue – but many philosophers say there are at least two, the other being the lump of clay of which Ned is made – call it Lumpy. Lumpy existed, in some sort of blobbish form, before it came to constitute Ned. And if we annihilate Ned, by say crushing him flat with a ten-ton weight, Lumpy may still exist (now in a very flat form). And possibly (maybe this is less obvious) we could modify Ned by replacing his parts one after another, so that it is no longer Lumpy which constitutes Ned, but instead some new quantity of clay.

As different things are true of them, we know that Lumpy and the statue Ned can’t be identical. But Brower and Rea would say that the two, though not identical, are “numerically the same”. So even though Lumpy and Ned are non-identical, the correct answer to “How many things are in the picture?” is: one. This, they admit, is odd, but they insist that any plausible metaphysics of material objects is going to say odd, unintuitive things sooner or later. (61-7)

What’s this got to do with the Trinity? Just this. They’re suggesting that God is related to each of the divine persons somewhat as Lumpy is related to Ned. As they put it, the divine essence eternally has the three properties of being a Father, being a Son, and being a Spirit, giving rise to three non-identical persons. They are, however, to be counted as one God, for they are all constituted by the same divine essence. (68-9) The divine essence “constitutes” each of the persons. None of the Three is identical to God, though each is “numerically the same” as the one God. (70) This theory, they claim, meets any reasonable desiderata for an orthodox doctrine of the Trinity, one consonant with natural readings of the Bible and the ecumenical creeds. (58-9, 70) Further, this solution isn’t plucked from thin air; they hold that common sense pushes us to believe that some things are constituted by others, and that there’s such a thing as numerical sameness without identity.

Technorati Tags: constitution trinitarianism, Mike Rea, Jeff Brower, lump and statue, identity, numerical sameness, material constitution

Pingback: trinities - Richard of St. Victor 7 – The Same Divine Substance (Scott)

Pingback: trinities - Linkage: Constitution Trinitarianism around the web

Yeah, that’s a better way of talking about it, since we needn’t talk about complex tropes. Very right. So what we say the trope being a father makes true pushes us towards LT or ST. If we say the trope being a father makes both ‘being a father’ true and ‘being divine’ true, then we’re pushing into the ST camp. If we say it just makes ‘being a father’ true, then we’re pushing into the LT camp. In other words, saying the trope being a father is a mere father-maker is different from saying it is a divine-father-maker.

Dear JT,

Yes, it does look like one might contrast accounts on which there’s one deity-trope and accounts on which there’re three deity-tropes. Leftow draws a contrast between LT and ST like this. This makes B&R’s view line up with ST, in addition to the contrast I drew between accounts on which there’s one basic divine subject and accounts on which there’re three divine subjects. This does imply, as you say, that each personal form makes the quasi-hylomorphic composite not only a person but also divine. I don’t see it follows, though, that each personal form has more to it or includes something else in the sense of each such form having a divine bit and a distinct personal bit. That is, I don’t see why such a form can’t be a simple, as opposed to a composite trope. As a truth-maker can make more than one truth true, so a trope can make more than one truth true. One could put this in terms of the having of universals rather than tropes. Nothing here turns on the choice.

Best,

Joseph

This is an interesting statement:

‘The way I see it, for B&R the divine essence is immaterial stuff (or an immaterial substratum), which is divine in virtue of being related to a divine personal form.’

So is the personal form the divine-maker? If that’s so, then each personal property would have to be a divine-maker, and that seems to me like social trinitarianism. This would be in contrast to the idea that each person is divine because they share a single divine-maker, namely the divine essence.

Also, if each personal property were a divine personal form, then each personal form would have more to it than just ‘being a father’, ‘being a son’, and ‘being a spirit’. Wouldn’t each also include ‘being divine’?

Dear JT,

Very interesting post. I’m not sure there’s anything here that’s specific to how B&R apply sameness w/o identity to the Trinity, but rather to hylomorphism more generally and perhaps whether one can apply this view to immaterial beings.

The way I see it, for B&R the divine essence is immaterial stuff (or an immaterial substratum), which is divine in virtue of being related to a divine personal form. Moreover, in ontology we must take some concepts as primitive: explanation must come to an end somewhere. Though we can say a lot and give many examples, the concepts of form, matter, and their unity might be good candidates for such primitive concepts.

One could hold another view, as you indicate, on which there’s a hylomorphic composite of stuff (or substratum) and a divine form and this composite combines with a personal property to compose a divine person. But I think this alternative would raise awkward questions, that one would prefer to avoid: what’s the status of the composite of stuff (or substratum) and the divine form? does it qualify as a divine mental subject or a divine person? if not, why not?

My main problem with B&R’s view concerns the ontology: I don’t see why we should posit stuff or substrata. But one doesn’t need this ontology to make use of the idea of sameness w/o identity. One might adopt Moreland and Craig’s view that there is one basic divine mental substance who has three divine minds and so constitutes three divine persons and say that, though each divine person is not identical to the divine substance, each divine person is numerically the same as the divine substance. One can think of this in hylomorphic terms: as Socrates seated is a composite of Socrates and being seated, so each divine person is a composite of the divine substance and a personal property. But my main problem with M&C’s view also concerns the ontology: I don’t see why we should posit coinciding entities, especially in the case of mental subjects.

What can you do? There are many many problems.

Best,

Joseph

Wow! Gentleman, thanks for the excellent discussion.

RichardH – “constitution” is supposed to be something objective in the world; if there’s such a thing, it isn’t constructed by theorists, but rather discovered.

Joseph – re: 1 – quite right. I was just trying to keep it simple in the first post. re 2: also important – I suspect there may be real objections lurking there… stay tuned. Thanks much for the background info in 3 & 4! I haven’t read the Markosian papers you refer to – I’m afraid Ned the Gnome was just lame alliteration. 🙂 I guess I don’t have strong views on whether there’s such thing as Aristotelian matter… though I probably should. :-0

Matthew: Good comments. I’m with you on #2. I don’t see how logically impossible scenarios (or ones we suspect are) are helpful. And you’re right – at best, their solution is of limited value. How many people actually believe that hylomorphism & numerical sameness without identity solve the problem of material constitution? Most metaphysicians, I’ll wager, don’t. I don’t even think there is such a problem. And ordinary folk have no interest in either the problem or the alleged solution. So at best, their theory will satisfy maybe .5% of Christians – maybe some subset of philosophy PhDs and grad students, and some small percentage of the philosophically sophisticated theologians out there.

JT – pleased to meet you! Please email and let me know who you are, just basic info, and give me (if you want) a cleaned up version of your long and interesting comment above, and I’ll put it up as a guest post, with a link to your post on your blog as well. I think your post is something we should be commenting on.

Pingback: trinities - Constitution Trinitarianism Part 2: Craig’s objections

Dear Matthew,

Re 3: When I said Rea has cornered the market, I meant in terms of setting out the problem and the different options for solving it. I didn’t mean that his own proposed solution has met with consensus or become the standard view.

Re 4: Of course, the folk wouldn’t use the technical terminology. But I think folk might say, e.g. a fist is a hand (substance) clenched (form). That’s not evidence the view is true, but it is evidence that it’s not that counterintuitive.

I have my own views also on how to solve the problem of material constitution: I lean towards mereological nihilism or else mereological universalism with essentialism. This is why I feel in no position to describe other views as wildly counterintuitive. Indeed, hylomorphism might seem tame in comparison.

Hi Matthew, Dale, and Joseph.

I just happened across this site and am pleased to see a few familiar faces here. Joseph, I know you (this is JT, from Oriel), and I think I may know you Matthew, or at least I know of you through a friend. Dale, I’m pleased to meet you. I too am super interested in all this trinitarian stuff, and I too have been thinking about Brower and Rea’s paper a little bit in the last few weeks. I’ve written my preliminary thoughts at http://jtpaasch.blogspot.com/2007/06/hylomorphism-and-trinity_17.html, but I’ll summarize them here. Maybe you all can help me clarify some things.

My main question for B-R is this: how exactly are we supposed to understand the divine essence as playing the role of matter? I see two problems with this. One is specific to B-R, and the other is more generally related to hylomorphism.

1. What do B-R mean by ‘form’ and ‘matter’, and how are they related so as to compose an object? B-R say forms are ‘complex organizational properties’. Presumably this means that forms are the sorts of things that organize or arrange material parts into a particular configuration (e.g., into Ned, into Athena, into Lumpel, etc.). If that’s right, then matter must be the kind of stuff that can be arranged.

If that’s how B-R see form and matter, this won’t work for the divine persons. The divine essence doesn’t have any material parts (and presumably is simple in the sense that it doesn’t have arrangeable parts), so what would the organizational properties (personal properties) organize or arrange?

Further, if the organizational properties (personal properties) can’t organize or arrange the divine essence, then how could such ‘organizational’ properties be related to the divine essence? I don’t see how they could in this sense. Without being related, the constituents of the divinity (essence and 3 personal properties) would just be a heap or a pile, and that’s clearly not what we want.

What we need is some sort of relation between a personal property and the divine essence which is unity-making, i.e., a relation which explains why the divine essence and a personal property make up a single person and not just a heap or pile of essence and property.

2. With respect to the particular claim that the the divine persons can be seen as hylomorphic compounds (call this claim HP, short for ‘hylomorphic persons’), the standard objection is this: in any hylomorphic compound, form is the feature-giver, not matter. By ‘feature-giver’, I mean that which gives a compound the features it has. In a human, for example, the human-maker of a human is the form, not the matter. The form is what gives the thing its human features, not the matter.

In the case of the divine persons, the personal property ‘being a father’ would make the compound a father. But the property ‘being a father’ is a father-maker, it’s not a divine-maker. Since the divine essence is supposed to play the role of matter, it can’t play the role of divine-maker, since matter doesn’t do that kind of feature-giving. Thus, we’d only get a _mere_ father, not a _divine_ father.

What we need in a divine person is for the personal property and the divine essence to both be feature-givers. The personal property ‘being a father’ should be the father-maker, and the divine essence should be the divine-maker. So if anything, we want the divine essence and personal properties to both be forms, not matter and form.

But it may be there are other views (unknown to me) on matter-form compounds which aren’t susceptible to this kind of objection. Are there any hylomorphism theories which claim that the matter is a thing-maker just as form? I don’t know, perhaps one of you could help me out.

Of course, one might say this objection takes matter as ‘prime matter’, and here ‘prime matter’ means featureless matter. Obviously, if matter is featureless, then it wouldn’t contribute any of its features (since it doesn’t have any) to the hylomorphic compound. But what about a ‘meatier’ sort of matter? Meatier matter would be any matter with some features. For example, bronze can be the matter of a statue, and bronze has plenty of its own features (it’s hard, it has a certain color, etc.). In these cases, the matter does contribute its features to the final product. Thus, a bronze statue is a _bronze_ statue because it is made from bronze, and consequently the statue has all the features of the matter (viz., of the bronze). The same would go for an _iron_ statue or a _clay_ statue.

Couldn’t we say that the divine essence is more like meaty matter rather than prime matter? Couldn’t we say the divine essence has certain features (all powerful, wise, good, etc.) and thus would contribute those features to each divine person in the same way that bronze contributes its features to a statue it makes up?

I myself don’t know enough about different versions of hylomorphism to answer this question. My intuition is to argue against this, for the following reason.

Meaty matter is ‘meaty’ because it has a form or forms which give it those features. Bronze, for example, just is some matter plus the form of bronze. So all the features of a lump of bronze are there because of the bronze’s form. Thus, there is no such thing as ‘meaty matter’ in the sense of matter itself having features. Only compounds of matter + form have features. Form is a feature-giver, matter is a feature-receiver.

I say that because of the following consideration. On the face of it, it seems sensible to say that a bronze Goliath is bronze because of its matter, while an iron Goliath is iron because of its matter. But would we say the same thing about a human Goliath? A human Goliath can’t be ‘human’ because of its human ‘matter’ (flesh and blood). If that were true, then we’d say that animals are human too, since they are made up of the same flesh and blood ‘stuff’. Rather, a human Goliath is human because of a human form. In other words, the human-maker is a human form, not the human matter. If that’s right, it would follow that the bronze-maker for a bronze Goliath would be the bronze form, not the matter.

But again, perhaps I don’t know enough about various theories of hylomorphism. Maybe one can say there is such a thing as ‘meaty matter’ in a way that would explain the divine persons. Any thoughts or ideas?

Joseph,

1. I think one could distinguish between hylomorphism and NSWI, though this might just amount to versions of a similar thesis. I don’t think there is one standard view of hylomorphism. (Certainly not in Aristotle!) So, there is room for variation.

2. I take it that part of the appeal of the model is that it works similar to an analogy. ie here is a model of how X works in Y domain, and here is the same model X applied in Z. If we think the model fails to explain things in domain Y, why should we have any confidence that it explains things in domain Z? If I recall, my reaction to Leftow’s use of time travel was something like, “well that’s interesting but of course time travel is impossible.” I don’t think you get much mileage out of these kinds of things.

3. Rea is a bright guy, but I don’t think it’s fair to say that he’s cornered the market on material constitution. Certainly those who hold differing views wouldn’t think this is the case! I recall that R&B made the equality assertion, but I don’t recall that R&B ever defend thesis that NSWI is just as counterintuitive as the other options. I have my own view on the matter, so I’m not up to just trusting Rea’s testimony.

4. Opinions differ. I’m sticking with wildly counterintuitive. It’s an interesting bit of anthropology that a lot of people believe would thing fists and smiles look a lot like hylomorphic compounds, but that’s a claim about the folks I’m not sure I believe. I’m sure the folk believe in all kinds of mid-sized objects, but they aren’t in a position to cache out those beliefs as hylomorphism. I’ve watched the revival of hylomorphism too, but we can hardly be surprised that some philosophers will try to revive wonky views. 🙂

I think it’s worth noting that even R&B “stop short of actually endorsing the solution that” they describe.

Dear Dale,

I think this a great start on Brower and Rea’s paper. I know this is only the first of many posts on the topic, but there’s something subtle that may give a few the wrong idea.

1. The divine essence, on this picture, isn’t God: it’s that which together with a form composes a divine Person. Each Person is a God, but each is the same God as the others, as each has the identical divine essence. So it might mislead to say God relates to each Person as Lump relates to Ned. B&R both think that something is (a) God if and only if it is a divine being but we count Gods by identity of divine essence, and so each Person qualifies as (a) God, but they aren’t different Gods.

2. If we think of what ‘God’ means (where (the) God exists if and only some God is the same God as every God), it turns out, in effect, that ‘God’ is ambiguous in reference, so that for each Person, there’s a reading of the claim that that Person is identical to God that comes out true.

3. I believe Jeff is into the idea that there’s a basic ontological category of stuff, but stuff isn’t an entity (even in the widest sense) and that the divine essence is divine stuff. I think Mike is more sceptical of the idea that stuff doesn’t even qualify as an entity. Ned Markosian has some good work on the ontology of stuff and things and their relation to each other, which is close to what Jeff thinks about this. Ned also has many on-line papers related to this topic, which are well worth a look. So it’s fitting your gnome is called ‘Ned’. I don’t know if that was on purpose.

4. Perhaps a bit of background on this paper might be of interest. I’ve spoken to both about the history of the paper. But we can gather most of what I’ll say from their work. Mike, in his doctoral dissertation, wrote on what’s called the problem of material constitution, and defended Aristotle’s solution, which uses numerical sameness without identity (NSWI). Mike around that time also came across a different solution, the one by Burke, which involves the idea of dominant kinds. I think Mike thought the honours were pretty much even between Aristotle’s and Burke’s solution. Jeff came across the idea of using NSWI while working on Abelard’s account of the Trinity. He read Mike’s paper on Aristotle’s solution and got in touch with Mike. Now that Mike sees how numerical sameness without identity not only solves the problem of material constitution but also the logical problem of the Trinity, I believe he leans towards Aristotle’s solution.

5. B&R distance their account from what they call Social Trinitarianism (ST). But it’s not clear to me why their account shouldn’t qualify as a version of ST. This is no doubt due to the problem that it’s not so clear what ST is. If the view is that in the Trinity there are three divine mental subjects, B&R think there are three divine subjects, and so on this description their account qualifies as a version of ST.

Dear Mattew,

Interesting post. I think I read your posts on B&R’s paper on the Trinity a while back. I’ll have another look.

1. Would you make a distinction between the use of hylomorphism as a solution to the problem of material constitution and the use of NSWI? Perhaps one might use the second without the first.

2. It seems right that for the most part if one thinks a theory false, one shouldn’t use it as a model for something. But it’s not clear this is so in all cases. It depends on why one counts the theory false and whether that applies in the case at hand. For example, I think Brian Leftow’s application of the idea of time travel (in ‘A Latin Trinity’) to the Trinity is interesting and helpful, even if, as I’m inclined to believe, time travel is impossible.

3. I think it’s right that it’s not enough to defend a view from being odd to say that all alternatives are odd: as you say, there are degrees of oddity. But it’s also not a decisive objection to a view that it’s odd if all others are at least as odd. I think Mike, who has cornered the market on the problem of material constitution, is well-placed to assess the relative costs and benefits of each proposal and that he does enough in the paper to defend its use here.

4. I’m inclined to reject hylomorphism, as I expect you are. But I think it too much to describe it as wildly counterintuitive. Even if one doesn’t say the most basic material substances are composites of matter and form, things many folk believe exist look a lot like hylomorphic composites of a substance and a form: e.g. fists, smiles, statues, mountains, and islands. Let me note that hylomorphism is also again becoming a respected view: Kit Fine and Mark Johnston, among others, are trying to put it back on the map.

Stay tuned, Matthew – I’m going to link all your posts during the series, as well as Craig’s piece.

I did a series of posts on Rea and Brower in February of ’06, and William Craig had a nice response in F&P entitled “Does the Problem of Material Constitution Illuminate The Doctrine Of The Trinity?”.

One of the things that I find curious is that Rea doesn’t think that hylomorphism works as a solution to material constitution. It’s odd that a theory one generally thinks is false should provide a positive model for the Trinity.

I also don’t think Rea and Brower can get off the hook by claiming that all the solutions to material constitution are counterintuitive. It’s not as if they are all equally counterintuitive! Some positions (hylomorphism) are wildly counterintuitive.

My first thought when I look at Ned is that I see a gnome, a hat, a belt, a beard, etc. I see the whole and I see the parts.

Or I might think I see, variously, a gnome or a picture or a gnome – or a picture of a model of a gnome.

Or I might think I see an illustration of a philosophical/theological issue.

Yes, somethings are constituted of other things. Makes sense to me. But one difference between a gnome and God/Trinity is who does the contituting. Ned, whether simply a gnome, a model of a gnome, a picture of a gnome, or an illustration, is constituted what it is by you the philosopher theologian. Ned (to the best of my knowledge has no opinion or power when it comes to his own constitution – “Hey! Let me out! I don’t want to be a philosophical illustration!”)

Going back to talking about God, I can’t imagine anyone other than God doing the work of constituting God. We philosophers and theologians might try constituting “God,” but that’s not the same.

So I’m curious where y’all go with this.

Thanks!

Comments are closed.