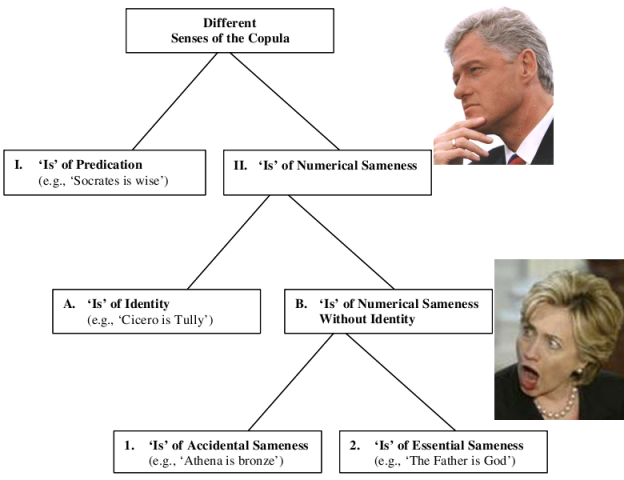

Is the Son God? In the immortal words of Bill Clinton, “It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.” Brower and Rea suggest the following classification of meanings of “is” (in logic, “is” is called “the copula” – that which connects the subject and what’s being said of that subject).

Um, no the Clintons aren’t in the original chart in their paper (71).

And yes, Bill is intrigued by the word “copula”.

It’s fair to say that most philosophers don’t believe there’s any such thing as the part Hilary is glaring at. (II.B.1 and II.B.2) This includes me, I’m afraid. In this blog, and in my published articles, I use “identical”, “one and the same thing as”, and “numerically the same” to all mean the important relation of identity – that weird relation which everything bears only to itself. Here are some random thoughts about their concept of “numerical sameness”, with the aim of helping you understand what they’re thinking.

- “Numerical sameness” is supposed to be symmetric and transitive.

- symmetric: If x is numerically the same as y, it follows that y is numerically the same as x.

- transitive: If x and y are numerically the same, and so are y and z, then it follows that x and z are numerically the same as well.) (66-7)

- They think that x and y can be qualitatively different – such that some things are true of x but not of y and vice-versa – and yet be “numerically the same”. They want to say that x and y are not identical, but are such that they (notice the plural) “should be” counted as one thing. While most philosophers think we should always count by identity, they deny that. (62, section 2.2) They suggest that most sorts of things should be counted by numerical sameness without identity, while other sorts of things should be counted by identity. (63)

- You’d think “numerical sameness” would be a one-one relation, i.e. the “two things” that stand in it are really identical. But no – a thing can be “numerically the same as” (say) seven-hundred non-identical things, and they can each be to it as well.

- I don’t grasp why they classify identity and numerical sameness without identity as species under a common genus. To put it differently, I think II.A should rather be III, as I don’t see what II.A and II.B have in common.

- Oddly, items which are “numerically the same” needn’t even be in the same category as each other. Hence, Socrates is in the category of substance, while “Seated-Socrates” is a mere “accidental unity” – not a substance, but rather a “hylomorphic structure” built of a substance (Socrates) and a non-essential property of that substance (seatedness). They hold the Father (etc.) to be “numerically the same divine individual” as the divine essence. (70) What’s an “individual”? I guess a non-substantial but property-bearing particular thing or entity. (This is yet another controversial claim – that there are such things. Again, it’s controversial that something could be “divine” while only being an individual and not a substance.) So again, substance on one side, non-substance on the other.

- Is this really monotheism? Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three non-identical, divine substances, though they are also supposedly “numerically the same without being identical”. What is unique, in the sense that nothing non-identical to it is numerically the same as it? “The divine essence.” But that isn’t a thing (substance) at all, only a stuff, much less a divine thing/entity/substance. Of course, it “constitutes” three distinct but “numerically the same hylomorphic compounds” – the three Persons. But on this theory, there is no divine person which is identical to God. So if by “God” you meant a “unique” divine person, in that sense they hold that there’s no God. Of course, what they want to say, is that the Three are to be counted as one God, in virtue of their sharing that something-like-an-immaterial-stuff. I guess it’s an oddball sort of monotheism, no more odd than many other trinitarian theories have it.

- In the plus column: this theory entirely avoids S-modalism.

That was all just circling around the issue and poking at it a few times. Well, why believe in this “numerical sameness without identity”? Have they been smoking crack? No – worse 🙂 – they’ve been out behind the barn metaphysicalizing like crazy, about material objects. It goes like this:

- You have intuitions about material objects like those in my Lumpy and Ned example. You don’t say, “there’s no such thing as Lumpy” (and/or Ned); rather, you believe there can be co-located things, at least if they’re of different kinds.

- In response to 1, you also want to say that while Ned and Lumpy are non-identical, there’s only one material object over there right now, where that Garden gnome is standing.

- If you’re still on board, you got what they call a “problem of material constitution” to deal with. (62) (You can join the club of philosophers in this book edited by Mike.)

- You read Aristotle (see their 60-1 & the sources in their footnote 14) and note his belief in what others have called “kooky objects” like “seated Socrates” – a thing which exists so long as Socrates is seated – and “standing Socrates” – a thing which begins to exist when Socrates stands up, annihilating “seated Socrates”. Maybe you’re not sure if you believe in such things or not (61) but what the heck – you decide that the relation Aristotle posits between Socrates and seated Socrates – “accidental sameness” – might apply to the objects of common sense. Maybe fists and hands are “accidentally the same”, and so are Lumpy and Ned.

- You note that things which are “accidentally the same” are the “same”, but might not have been. And you say, well, maybe things can be the “same” but are such that they can’t not be the same. So you generalize, hypothesizing that there are two kinds of sameness without identity, the accidental and the essential kind.

- Happily, this last relation seems fit for duty when it comes to trinitarian theology.

My point in spelling this out, beyond making their motivations clear, is just this: it all hinges on 1. I don’t have those intuitions, so I get off the bus there. While it’s convenient to think and talk about that batch of atoms (or maybe fundamental particles) over there as “Ned” the statue or, maybe for some different purposes as “Lumpy” the lump, I don’t think there are such objects (what Aristotle calls primary substances) in the world. In my view there just a series of causally and spatially related events, which for our purposes we think of as things (which last through time and change). In Buddhist terminology, “Ned” and “Lumpy” are no more than “convenient designations”. Is this a violation of common sense? It depends what you mean by common sense. If it’s the set of things which normal adult humans in normal circumstances know, then I don’t think so. It is against common sense, in that it seems natural to believe at least in things like statues (I not so sure about lunch.) But in any case, how can this be a required Christian belief, when many Christians, such as me, have contrary intuitions, ones which in no obvious way contradict scripture, or even the creeds? And a great mass of others, will simply lack any relevant intuitions. The answer seems to be: it can’t be. But if you’re going for a great-creed-consistent doctrine, it has to be required. (E.g. See the nasty clause at the start of this.)

Technorati Tags: Mike Rea, Jeff Brower, Aristotle, lump and statue, identity, numerical sameness, material constitution, form, matter, Athanasian Creed

Pingback: Scott Williams’s new paper: Henry of Ghent on Real Relations and the Trinity (Dale) » trinities

Pingback: trinities - Richard of St. Victor 8 – A Proposed Constitutional Trinitarian Taxonomy (Scott)

Pingback: trinities - Richard of St. Victor 8 – Constitutional Latin Trinitarianism? (Scott)

Pingback: trinities - Constitution Trinitarianism Part 4: pausing and revisiting some issues

I think this argument links numerical sameness without identity too closely to the issue of material constitution. For one thing, you can generate an argument for numerical sameness without identity on anything you can consider mereologically, since it is a solution for a general mereological problem — and since we can consider spatiotemporal events mereologically, merely switching to them doesn’t really change much. Material constitution is just one way of proposing a position that holds numerical sameness without identity.

Further, there clearly are things that are usually considered sameness relations that are not identity; mathematical equality is one of them. 2 + 2 = 4 is usually read as a claim that both sides of the equation are the same, but it is not a claim that the expression 2 + 2 is just the same expression as 4; which is good, because they are different constructions. Then there are intersubstitution problems in modal and epistemic contexts, which also have been proposed as a reason for accepting some form of numerical sameness without identity (since they indicate cases where we have to regard things as the same which differ in some respect, e.g., in how they can be substituted into epistemic contexts).

So someone can propose a position involving numerical sameness without identity, without touching material constitution. Material constitution is simply the most popular way to do it at present.

Yeah, scratch my comment number 9. Here it is, rewritten without the mistakes.

In the traditional western view of the trinity, e.g., as the likes of Augustine and Aquinas think, the divine essence basically functions as a nature.

Of course, the classical (Aristotelian) sense of ‘nature’ is a little tricky. For most theologians such as Aquinas, a nature in created things is particular in the way that a trope is considered particular. Further, Aquinas would distinguish between nature-tropes and accidental-tropes. Plato’s humanity would be a nature-trope, but Plato’s paleness would be an accidental-trope. Additionally, nature-tropes are instantiated by matter, and that makes a substance (in the sense of an individual object). Accidental-tropes are instantiated by substances.

Here’s the key points about this classical view.

(1) Both of these kinds of tropes are posterior to their subjects (i.e., to their trope-bearers). The reason is that they are instantiated by their subjects, not the other way around. Perhaps another way of putting this is that the natures are posterior to the things that exemplify them.

(2) Also, natures are not individual objects. They do have some extramental reality in the same way that the modern notion of tropes have some extramental reality, but they are not individual objects. They are rather traits or attributes of individual objects. Socrates and Plato are individual objects, while ‘humanity’ is an attribute of Socrates and Plato rather than an individual object in its own right. But nevertheless, ‘humanity’ does have extramental reality because it’s really ‘there’ in Socrates and Plato.

As I said at the beginning of this comment, the divine essence functions in the same way. It is posterior to the persons, just as ‘humanity’ is posterior to Socrates and Plato. And the divine essence is not an individual object, but it does have extramental reality in the divine persons because it’s really ‘there’ in the Father and Son. Likewise, the divine persons are, in some sense, individuals just as Socrates and Plato are individuals.

The major difference between the divine essence and natures in created things is that natures in created things are multiplied by their subjects. Thus, Socrates’ humanity is not identical to Plato’s humanity. As I said, natures in created things are more like tropes because they are particular for each individual instantiator.

The divine essence, on the other hand, is like an immanent universal. It is not divided by each divine person which instantiates it. Thus, each divine person shares the numerically same nature (the divine essence). It would be as if Plato and Socrates shared the numerically same humanity. Apart from that, the divine essence basically operates like a nature.

B&R’s account is pretty much the complete opposite of this. The divine essence is like the subject which instantiates the personal properties.

I wonder about some of the things that this might entail.

(a) One might argue that the divine essence has to be an individual if it is to instantiate anything. This would be an argument similar to Scotus’s argument for individuation: any of the obvious candidates for individuation (e.g., matter, accidents, etc.) are already individual, so they must already be individuated and thus can’t function as individuators. There must, then, be something individual itself (a haecceity) which instantiates any properties and makes them particular.

I myself am not necessarily opposed to saying the divine essence is an individual. I certainly don’t want to identify the divine essence with the father, because that would lead to the ‘derivation’ view of the trinity, which doesn’t seem to me very workable.

(b) One might further argue that on this view, the personal properties have to be like natures in that they are instantiated by the divine essence. B&R certainly seem to talk this way when they say that matter instantiates forms. But if this is right, do we then mean that the personal property being a father is the generic nature paternity? That would seem to go against the whole ‘generic’ view of the classical tradition, where the divine essence is seen as the generic nature of the persons, not the other way around. And what sort of consequences would this entail?

I don’t know how I feel about this particular point. In principle, I see no reason why the personal properties can’t be seen as generic natures.

(c) I have further questions (as does Joseph) about what any of this means for the question ‘one consciousness or three?’ For the classical view, does saying the divine essence is an immanent universal block the inference that there are three consciousnesses? Likewise, for B&R’s view, does saying the divine essence is the subject of the personal properties block the same inference?

With respect to the classical view, I’m inclined to think that there is one consciousness. The divine essence is the thinking and willing power-pack, and since the divine persons are the subjects of that power-pack, there would certainly be three agents which do the thinking and willing. But since they all share the same thinking and willing power-pack, they would all perform the numerically same acts of thinking and willing, and I’m not sure that gives us enough to say there are three distinct consciousnesses. But my mind is not totally made up on that yet.

With respect to B&R, I don’t even know how to go about answering the question. They haven’t really clarified their position enough yet.

I just read that again, and realize that there’s a lot of equivocation there depending on which version of Aristotle and modern analytic philosophy I was thinking of. If I get a chance, I’ll clean it up.

Most of the western theologians such as Augustine and Aquinas held the divine essence to be logically posterior to the persons, much the same way as the nature ‘humanity’ is logically posterior to Socrates and Plato. The idea is that individuals/substances instantiate natures, not the other way around.

This is also the reason the divine essence doesn’t count as an individual/substance (just as natures don’t count as individuals/substances either), whereas the divine persons in some sense do (just as Socrates and Plato do).

In any case, this is yet another point I find strange with respect to the claim that divine essence is like the matter of the divine persons. If it’s the matter, it’s logically prior to the divine persons. That can have a number of entailments, depending on how strongly they want to hold to aristotelian thinking.

It can entail, for example, that the divine essence has to be an individual in some sense (I myself am not adverse to holding such a view). Or it can entail that since the divine essence (as matter) instantiates the persons (and not the other way around), then the personal properties have to be like natures, since matter instantiates natures (rather than, say, properties….for Aristotle substances instantiate properties, not matter). Again, I myself am not necessarily adverse to saying such things, but it remains unclear to me whether B&R have thought this far down the line of entailments. I suspect they haven’t, because if they did, I’d have a much clearer statement on what ‘matter’ and ‘form’ is supposed to mean in this context.

“I wouldn’t describe this as van Inwagen’s or Merrick’s view”

Oops! I just noticed on my original post I wrote “Or do you have an ontological view like Van Inwagen and Terence Parsons? ” where what I meant to say was “Or do you have an ontological view like Van Inwagen and Trenton Merricks?” Sorry, I was thinking of Trenton and similarities in first name forced the slip (I do the same thing with Petit and Percival – I tend to write one when I really meant the other).

Hi Dale,

“I don’t think = can be a constitution relation – they all that there are = relations as well, and a thing can’t be it’s own matter, I think. ”

I agree – constitution is an asymmetric relation. I think the initial part of my comment wasn’t clearly stated – what I meant to say was that in my definition of “being involved in a web of material constitution relations with” I was using “constitution” to cover both constitution and identity. This was merely to simplify the definition and was both unnecessary and probably misleading.

“I don’t see why they couldn’t say that the essence and its three forms are equally prior, equally fundamental, all occurring together in all possible worlds, and none of them really explaining the others. You’ve got four ultimates then, but maybe they can live with that… people will differ perhaps on how high a “cost” that is for the theory. ” I don’t think they can say that all three are equally fundamental since constitution is precisely a kind of metaphysical priority relation – the existence of the three persons depends on, is there in virtue of, or is grounded in (or however you want to say it) the divine essence. If this is denied, then I see no way that one could maintain that there are any constitution relations involved whatsoever.

As for the stuff about having to believe in a particular theory of the Trinity, I think there are few things to be said here: First, one could make a distinction between the doctrine of the trinity and particular theories thereof. The doctrine forms (perhaps vague) boundaries of orthodoxy which any theory of the trinity must fall into and which no beliefs may fall outside (no tritheism, for instance, or denial of the deity of the three persons). It’s a bit like what we might call “the doctrine of physical objects” – one can believe in physical objects and lots of stuff about them and this can rule out certain theories and yet leave room for debate as to what theory will best capture this prior doctrine. (Note that one could believe in the doctrine but also believe in a theory which is inconsistent with it because, among other reasons, one might not realize that there is such an inconsistency)

Another track would be to insist that when you say, “I guess they could get out of all these complaints of mine by just saying – like I believe many Catholic theologians have – that all the Church really requires of believers is assent to words, whichever the Church lays down, as well as a resolution to believe – should they ever be able – what the Church means by those words. This idea sticks in my craw – it means that pew-isitters are treated like children… I don’t see that any human short of Jesus, a prophet, or an apostle has quite that kind of quasi-parental authority over them – not because I’m stubborn, though I am – but because I don’t see any NT basis for the idea.” that this isn’t really as bad as you make it sound – it’s just one more instance of linguistic division of labor. As I understand it, the deferential linguistic attitude would be a sufficient though not necessary means to expressing, asserting, and believing the appropriate doctrine. Of course, such an attitude would not be necessary and one could have a direct, non-deferential belief instead. It’s getting the view right, not the deferential means to getting it that is important. In that light, the sort of view you mention in the quote above doesn’t really seem that strange or repulsive – it’s a pretty ordinary sort of thing, really (that’s not to say, of course, that there might be other things wrong with it).

Dear Dale,

I hadn’t read your reply to Ian before I sent my post. Now I have, here are two further comments.

1. I understand your view about material beings better now. We are immaterial simples. There are elementary particles arranged in various ways but they never compose anything. I wouldn’t describe this as van Inwagen’s or Merrick’s view, each of whom believe in material composites. So the world is a world of simples. Strictly, though, there’s no entity that is the world: there are simples arranged world-wise. Cian Dorr comes close to this view, except he thinks we don’t exist. I’m very much inclined to accept that there are only simples, but I concede that it’s highly counter-intuitive. This, it seems to me, is in the spirit, if not the letter, of the views of Antoine Arnauld, Pierre Nicole, Joseph Butler, Thomas Reid, Roderick Chisholm, and Dean Zimmerman, except I think each of them is best described as holding mereological universalism and essentialism. One problem for the view that there are only simples, apart from being highly counter-intuitive, is that it must deny the possibility of gunk: atomless stuff, where atoms are simples.

2. I don’t think belief that the doctrine of the Trinity is true is essential to salvation, as opposed to belief in the Trinity. I suppose one could hold a view of theological semantic deference. Just as Putnam says we semantically defer to scientists for the meaning of natural kind terms, so we might say we semantically defer to the Church’s theologians for the meaning of Christian doctrinal terms. But we needn’t hold this view. B&R’s account gives us a good analogy here. Folk have many beliefs about material beings: arguably they believe there are statues, lumps, lumps can survive radical change of shape, and statues can’t, but there’s only one material being, at least many are disposed to accept these things. Perhaps they believe these things but they don’t know how it could be that all these things are true together. Either they see no problem or if they do, they don’t know how to solve it. Just so, Christians have many beliefs about God: they believe there is one God, three divine Persons, and each divine Person is God, at least many of them are disposed to accept this. Again, perhaps they see no problem here or do, but don’t see how to solve it. So they accept the doctrine of the Trinity but don’t accept an Aristotelian solution to the logical problem of the Trinity. After all, most have never read any of the relevant writings on the matter. I don’t see why Brower and Rea can’t accept all this. Their solution doesn’t imply that Christians accept this solution, even implicitly.

Best,

Joseph

I am enjoying this series of posts very much. You seem to have attracted some good comments too. Let me, as I tried to do with Moreland and Craig, defend Brower and Craig here.

1. Numerical sameness is an equivalence relation (i.e. reflexive, symmetric, and transitive). I take it that what unifies each numerical sameness relation is that each is an equivalence relation by which we count: which relation we count by depends on which kind the entities we count belong to.

2. The divine essence is either divine stuff or a divine substratum. Either way the divine essence doesn’t qualify as a divine individual, divine Person, or God. So either way it’s false that each divine person ‘is numerically the same divine individual as the divine essence’, for I presume x is numerically the same F as y iff each of x and y is an F. And, as far as I know, B&R never say this (not on p.70 anyway). One might say the divine essence is numerically the same as (but not identical to) each divine Person or one might deny it’s the same as any divine Person. If the first, it’s false the divine essence is such that ‘nothing non-identical to it is numerically the same as it’, i.e. it’s false the divine essence is such that everything numerically the same as it is identical to it. If the second, it’s false each divine person is even numerically the same as the divine essence.

3. I don’t see why B&R need think of an individual in any fancy sense here: it’s an entity, a particular, and a property-bearer for sure, but why think it non-substantial? I see no reason why they need to make a distinction between individuals and substances here, unless, of course, they take the divine essence to be an individual. So, as I see it, for them, each divine Person is an individual and a substance. The only question is whether the divine essence should qualify as an individual but not a substance. But if the divine essence is an individual, it’s not a Person and so not a God. So there’s no question of saying the Persons are individual non-substances but God is an individual substance.

4. Monotheism is the claim that there’s one God. On B&R’s account, there’s one God and so monotheism is true. It all turns on whether one permits their definition of a God: x is a God iff x is a (quasi-)hylomorphic composite whose stuff is some divine essence; x is the same God as y iff each is a God and they share the same stuf; there’s one God iff some God is the same God as every God; and x is God iff x is a God and there’s one God.

5. Why think there’s a sense of ‘God’ on which it means the one and only divine Person? If so, if, in effect, the concepts of a divine Person and God coincide, there can’t be three of one and one of the other: this would be enough to show the doctrine of the Trinity incoherent. On their view, what ‘divine Person’ and ‘God’ mean permits it to be that there are three divine Persons (and one can’t also count one divine Person) and there is one God (and one can’t also count three Gods). So on their view, there’s no sense in which there’s no God.

6. Here’s a compressed version of the problem of material constitution. It consists of five claims each of which seems right but which are inconsistent with each other. First, there are composites. Secondly, composition is unique. Thirdly, composition involves an essential relation R: if the x1s compose y, then for some z, the x1s compose z and it must be that for any x2s, if the x2s compose z, then z bears R to the x2s. Fourthly, composition involves a non-essential relation S: if the x1s compose y, then for some z, the x1s compose z and it could be that for some x2s the x2s compose z and z doesn’t bear S to the x2s. Fifthly, identity is permanent and essential. In short, the problem arises when and only when it seems that for some x and y, x and y have the same parts as each other but relate to those parts differently. A solution to the problem of material constitution rejects one or more of the five claims. This is a kind of paradox. One needs not only to reject one of the claims but also to explain why we, at least initially, think the claim right. So here’s my first question: what’s your solution?

7. I don’t get the section where you set up the problem of material constitution and explain where you stand. Here are some questions. What intuitions don’t you have? That there aren’t composites? That there aren’t coincident entities? You say there are atoms or elementary particles arranged in different ways. But then you say there are no substances. Why don’t particles qualify as substances? Then you say there are only events related in different ways. Here are more questions. Do you think we exist? What are these events? Is this a perdurantist view where something persists if it has different parts or counterparts at different times? I guess not, else you wouldn’t need to deny the existence of artefacts or masses. Is this a Chisholmian view where statues and lumps are entia successiva, which are logical constructions of different things that do duty for statues at different times and are, strictly speaking, only fictions? And what’s this about lunch?

8. It must be that if one accepts the traditional creeds, one accepts the doctrine of the Trinity and so one should believe that there’s some solution to the logical problem of the Trinity, even if one doesn’t know what it is. But it doesn’t follow from this that one needs to accept B&R’s account.

Hi Ian,

This stuff is slippery, isn’t it? It took me quite a while to really understand what they’re doing. I don’t think = can be a constitution relation – they all that there are = relations as well, and a thing can’t be it’s own matter, I think.

Re: the divine essence (really: something-like-a-matter – they really call it that, I think, just to have a link with the tradition which talks alot about the ‘godhead’ or divine essence), when I first read them, I thought they were identifying it with God. That’d be the natural route to take, and at least one other recent philosopher has explored it. But no, they take the ambiguity route that you mention. I’m going to cover that, I think in the next post.

About priority, they could say that the divine essence is what’s most metaphysically prior… but I don’t see why they couldn’t say that the essence and its three forms are equally prior, equally fundamental, all occurring together in all possible worlds, and none of them really explaining the others. You’ve got four ultimates then, but maybe they can live with that… people will differ perhaps on how high a “cost” that is for the theory.

Re: material objects, I’m inclined to take a view like van Inwagen’s, although I’m a dualist, and have never bought his idea that a “life” could do the work he thinks it can.

About the final point: Brower and Rea are looking for a view which is orthodox in the creedal sense, that it doesn’t violate at least: the Athanasian Creed & the Constantinopolitan creed, and I suspect that at least Brower would like it to fall in line with the Augustine-Aquinas tradition of trinity theorizing as well. My thought was this: those creeds embody the idea that orthodox beliefs (or at least orthodox confessions) are mandated by Mother Church. The idea: You WILL believe (or at least say) these things, or you will not receive the grace of God which we uniquely dispense, and bluntly, you’ll go to hell. I don’t see how *belief* in a theory like this could be mandated, given how sophisticated you have to be to even understand it. That was my main point.

And on a different note, many hold the doctrine of the Trinity as a consensus belief, arrived at through common efforts by previous incarnations of the Church, or at least the leadership thereof. If *this* is what the doctrine is, I don’t see how it could be so. They just didn’t posses the tools to distinguish identity from numerical sameness without identity, most of them, and specifically the bishops at all the councils who came up with the standard formulae. (In other work, Brower shows that Abelard held something in the ballpark, but not quite what they’re defending here. But Abelard was like the van Inwagen of his day – and I mean that in a sense favorable to both of them.)

I guess they could get out of all these complaints of mine by just saying – like I believe many Catholic theologians have – that all the Church really requires of believers is assent to words, whichever the Church lays down, as well as a resolution to believe – should they ever be able – what the Church means by those words. This idea sticks in my craw – it means that pew-isitters are treated like children… I don’t see that any human short of Jesus, a prophet, or an apostle has quite that kind of quasi-parental authority over them – not because I’m stubborn, though I am – but because I don’t see any NT basis for the idea.

I definitely sympathize with your comments about numerical sameness. In my mind “numerical sameness” is a misleading designation that just means “being involved in a web of material constitution relations with”, where (to give a recursive definition) x is involved in a web of material constitution relations with y iff there is a z such that z bears a constitution relation to both x and y or x and y are involved in a web of material constitution relations with each other (assume that every identity also counts as a constitution relation). But if that’s all it means, I don’t see how “one” is the answer we OUGHT to give to the question of how many Gods there are.

Sure, using ordinary patterns of speech, we surely CAN do so. After all, ordinary speech seems to me in its practices of counting to speak rather loosely at times – when confronted with temporarily coincident entities (if there are any), we just count one of them since for most practical purposes there is just one material object present and ignore the others. Or we restrict our quantifiers so that only one of the many coincident entities shows up in our domain of quantification so that we get an answer of “one” when asked how many objects there are there. There are some other sources of sloppiness here as well. This process of counting (if it is even to be called that – some, like Ted Sider, insist that counting is necessarily, analytically, always by identity) is interesting and useful for us, but metaphysically uninteresting. If there are three non-identical divine substances involved in a web of material constitution relations with each other, then while loosely speaking it can in ordinary speech be okay to say that there is only one divine person, strictly speaking there is three here and no single God to be found.

To get an even better grip on this strangeness – consider what, under their view, the name “God” refers to. Either it must be ambiguous so that it can refer to each of the divine persons depending on with which meaning it is used or it must be vague so that it has no definite reference but the three divine persons are the “candidate referents” so to speak. There is no single entity which we can properly be referring to as “God” under this theory. So it’s not even clear what we would mean by “The Father is God” under this theory.

One COULD take God to be just the divine essence, but that would be rather bizarre since God is personal, etc. whereas the divine essence isn’t even supposed to be an individual in the first place.

Another potential problem is that many folks like to think of God as prior to all else and that there is no ingredient of reality that is metaphysically prior to God – God is ultimate. But this view makes God (or at least the three divine persons) metaphysically non-ultimate since they all depend metaphysically on the divine essence. Relatedly, for those gung-ho about divine simplicity, there is also cause to worry that, being constituted out of something else, no divine person will count as simple in the relevant way since it is made up of something else.

Dale: as far as your positive take on Ned and Lumpy, I’m really not sure what your personal view amounts to. Are you denying that there are any material objects? Reducing them to or eliminating them in favor of processes? Or do you have an ontological view like Van Inwagen and Terence Parsons? I admit that these sorts of views have their attractions and that you can certainly reconcile them to some extent with our ordinary speech and thought but to deny that Ned and Lumpy exist is certainly still counterintuitive and a cost to any theory (though, of course, every theory has its costs and this one may very well be worth paying).

I’m not sure what the force is of your question, “But in any case, how can this be a required Christian belief, when many Christians, such as me, have contrary intuitions, ones which in no obvious way contradict scripture, or even the creeds?” since neither Brower nor Rea claimed that there view was required. Even if their view of the Trinity turned out to be true or rationally compulsory I don’t see why it would have to be a required Christian belief. So I’m not seeing the connection with their theory. I’m still a bit confused also as to what you had in mind in your last few sentences of the post: “The answer seems to be: it can’t be. But if you’re going for a great-creed-consistent doctrine, it has to be required. (E.g. See the nasty clause at the start of this.)” Maybe if I understood what you’re getting at here I’d have a better grasp on the earlier question you asked.

Anyway, thanks for another nice post.

Comments are closed.