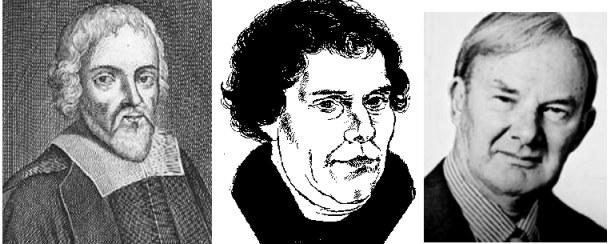

Three famous Revisers: Socinus, Luther, and Hick.

Unlike Redirectors, Revisers don’t change the subject. Unlike Resisters, they don’t claim we should just “live with the tension”. Unlike practitioners of Restraint, they don’t think we can put off the issue. Like Resolvers through Rational Reinterpretation, they have a solution. But they don’t think tricky, new, more careful formulations are what is called for. Rather, something must go out on the rubbish heap. Revisers are usually accused of arrogance, lack of respect for tradition, biblical ignorance, idolatry of human reason, not being Christians at all, and of hating babies and cute little puppies.

Open theists are Revisers about divine (unchanging and unincreasable) foreknowledge and human freedom. Many Christian philosophers who are trinitarians Revise traditional theology by denying medieval doctrines of divine simplicity, which seem incompatible with multiple persons “in” God. John Hick is a Reviser about the Incarnation and about traditional Christian non-pluralism. Socinus Revised with respect the Incarnation, the Trinity, and other matters. Luther Revised many medieval Catholic doctrines which he thought contrary to scripture and/or reason (he emphasized the former).

I divide Revisers into two groups: Reforming revisers, and Reinventing revisers. The former want to change accepted Christian doctrine to bring it into better accord with some authority or which it is (supposed to be) founded, and from which it has despite itself sadly strayed – such as the Bible, reason, the apostolic tradition, the church Fathers, or all of these. In contrast, Reinventing Revisers think that Christian theology is something which ought to be remade by each generation, or anyway, but us, because of some important developments in other areas of human knowledge, usually the almighty Science. They either de-emphasize core, un-negotiable Christian beliefs, or deny that there are any such. “Liberal” theologians such as Hick are Reinventers. Luther and Socinus were Reforming Revisers. So, I suppose, were the Catholic leaders at the famously revisionary Vatican II council.

The price? The Reviser is a heretic with respect to his base community, the one he urges should change – he denies something they affirm as essential. This is a main difference between the Rational Reinterpreter and the Reviser – the former is kind of/sort of/arguably/maybe orthodox, while the latter is confessedly not. Say what you will, Revisers pay the price for their conviction. Because of this heresy issue, offended traditionalists don’t see a lot of difference between a Hick-type reviser and a Luther-type one – a heretic is a heretic. The Vatican II guys, of course, didn’t face this problem; being at the top of the hierarchical heap, there was no one above them to thunder down condemnation – only hacked off traditionalists who were then marginalized. It’s good to be the King.

I would argue that in general, Revision should be considered a last resort, or at least, something one considers only after trying out the various Rational Reinterpretations and perhaps some sort of Resistance. It seems to me that we ought to assume that our forerunners were on the right track, until the evidence compels us to deny this.

I’m an open theist, but before I became one, I was as eager as anyone to show the compatibility of human freedom and divine foreknowledge. I became an open theist as a grad student at Brown, after I read through all the various schemes which allegedly show how traditional (unchanging, all-encompassing, certain) divine foreknowledge was compatible with human freedom. It seemed to me that all such solutions faced some steep philosophical problems, and biblical ones as well – ones which eventually made open theism look plausible by comparison. The mysterian Resistance views I previously held (as well as my previous habits of Restraint and Redirection) seemed more and more lame, the more I (1) looked very carefully about all the Bible did and didn’t say on the issue, and (2) looked into arguments for the logical incompatibility of human freedom and divine foreknowledge (as traditionally understood). (BTW – beware of philosophers peddling the notion that these arguments all involve some logical fallacy or other – most do not!)

Is Revision reasonable? It all depends on the specifics of the case. With that unsatisfying and trivially true conclusion, I end this over-long series.

I should add that I’m actually inclined towards the view that it is precisely *A-theoretic* views of time that are incompatible with libertarian freedom and/or moral responsibility(I’ve been developing various arguments to show this for various versions of the A-theory, presentism included – I’m delivering a version of one of these actually at the upcoming Eastern APA meeting for the phil time society).

Thanks for the clarification Dale. I guess I simply have no idea how a B-theoretic view all on its own could be incompatible with libertarian freedom without sneaking in some A-theoretic assumption (that is, without already assuming that the tensed treatment of some temporal phenomena – agency, say – is the correct one) or making an assumption an indeterministic, arrow-of-time-respecting B-theorist ought to reject anyway. As someone whose primary work is in philosophy of time, if you’ve got a plausible B-theory and you reject determinism, I see nothing to stop anyone from having an unconditional ability to choose or do otherwise. Certainly, nothing follows directly from the B-theory one way or another, once it is properly understood (which, from my reading, most A-theorists do not – indeed, many B-theorists don’t understand it completely either). I think it ultimately comes down to whether you’re inclined to the A-theory – something I’m sure we won’t agree upon!

Hi Ian,

It’s very easy to “make them compatible”. Just go for some sort of compatibilist theory, or be a confused libertarian. The latter, I think, is the more popular route among recent Christian philosophers (e.g. Craig, Plantinga). No “no future” assumption – in some sense there are at least some future facts – just the firm conviction that freedom requires an *unconditional* ability to (sometimes) choose or do otherwise. I am now committed to presentism, and was implicitly back then. I think B-theory views are incompatible with libertarian freedom.

Not to steer things into a tangent, but I was wondering what, philosophically speaking, made you come to think freedom and foreknowledge are incompatible. It would seem to me pretty easy to make them compatible. Of course, to do that you can’t be a presentist or growing block-er – if my own free actions do not ground God’s knowledge of them, I would agree that they couldn’t be free. Was there some “No Future” assumption behind this move to open theism? If so, I would say you gave up on the compatibility of foreknowledge and freedom far to easily (of course, I’m a bit biased here – I have very definite views on the philosophy of time)!

Comments are closed.