Last time I offered a definition of the concept of a trinitarian.

Last time I offered a definition of the concept of a trinitarian.

This time, I will try to define the concept of a unitarian.

Many definitions of this concept are unacceptably polemical. It is unacceptable to define a unitarian as an anti-trinitarian. This violates requirements 3 and 5 – it doesn’t tell us what a unitarian is, but only what a unitarian is against. And this is part of a common slashing rhetorical strategy which I have recently mentioned. For the same reasons we must reject defining the concept unitarian as one who “denies the Trinity” or “has heretical beliefs about the Trinity,” etc. Equally, it is unacceptable to define a unitarian as one who holds the correct or biblical view about Jesus and God. Whether or not that’s so, it’s trying to sneak an argument for a thesis into a pseudo-definition of that thesis.

One common definition is,

Definition 1: someone who believes in exactly one unipersonal God.

I think this is on the right track, but the term “unipersonal” is obscure, and so this definition violates requirement 6 (and possibly also 3).

I have been working with this definition of the concept:

Definition 2: someone who believes that the one God just is (is numerically identical to) the Father.

I now think that this isn’t quite right.

First the definition is arguably too narrow. Suppose there’s a native American who believes in the Great Spirit and conceives of this as the one God. It seems that this person should count as a unitarian, but he would be excluded by definition 2.

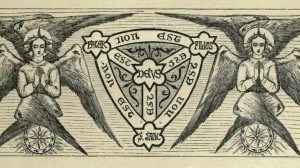

But it is also too broad, for it will include some Christian trinitarians. Consider someone who thinks that the one God is numerically identical to the Father, and also to the Son, and to the Spirit. That is, someone who looks at the traditional Trinity shield and reads every occurrence of “is” there (in the Latin chart here: “est”) as expressing numerical identity.

This theory is demonstrably incoherent (self-inconsistent). But never mind that. The point is that this person should not count as a unitarian. In short, it is not sufficient for being a unitarian that one accepts the identity of the Father and the one God.

Definition 3: someone who believes that the one God just is (i.e. is numerically identical to) a certain self and not to any other self.

I think this is right. Any objections?

Since identity is a 1 to 1 relation (it is incoherent to suppose that one thing is identical to more than one thing) the last clause may seem superfluous. But since a unitarian is by definition not a trinitarian, I think the clause is necessary.

Note that this definition requires a unitarian to be a monotheist, and also the sort of monotheist who considers God to literally be a self, that is, a subject of thought and intentional action. There are of course some people in every supposedly monotheistic tradition who think that God is only metaphorically a self, that is, somewhat like a self. These folks often think that we get all of our concepts from sensory experience, and so the concept of a self just is the concept of the human animal. I don’t think this is correct; there is a more abstract concept of a self which does not imply being a human being. In any case I think this restriction is correct; unitarians think that God is a certain magnificent, perfect self. And so some Christians, some Jews, and some Muslims will be unitarians, but others in those groups will not, for instance those under the sway of neoplatonic philosophy, who think that God is ineffable (such as to not satisfy any concept we have), or “Being itself,” or The Good, or The One, etc.

Building on this definition of unitarian, a Christian unitarian would be defined as: someone who believes that the one God just is (i.e. is numerically identical to) a certain self, namely the Father, and not to any other self.

Note that there is nothing about christology here; I think this is also correct. Trinitarians are often sloppy about defining their thesis, sometimes equating it was the idea that Christ is divine, or that Christ is as divine as the Father. But trinitarianism and unitarianism are in the first instance theses about the one God. Is Christ in some sense divine? That is a further question. All trinitarians will answer affirmatively, but so will some unitarians.

Some Christian unitarians past and present define their thesis as the claim that Christ as a human nature but not a divine nature – that is, they define a unitarian has what I have called a humanitarian unitarian (what is nowadays often called a “biblical unitarain”), understood as implying that Jesus existed no earlier than his conception. But this definition is plainly too narrow. There have been a number of famous unitarians, including Biddle, Clarke, Worchester, Emyln, Origen, and Arius, who have thought that Christ existed before his conception and in some sense had a divine nature. In short, the definition of a unitarian should be neutral on the matters of the divinity of Christ and the “pre-existence” of Christ.

One may object to definition 3 that it makes Oneness Pentecostals unitarians, and so is too broad. I think the definition does include them, because they assumed that the Father and Jesus are one and the same self. This position is patently incoherent, because by their own lights (as well as by ours) some things are true of the Father that are not true of Jesus, and vice-versa. But even though it is incoherent, I think it is a type of unitarianism, and also, Christian unitarianism.

What about other Christian modalists? Recall that the point of such theories is to reduce the number of divine selves down to one, either God or the Father, the other “persons” been modes of him, ways he is. They would satisfy definition 3 of the concept of a unitarian, but interestingly, whether or not they satisfy my definition of Christian unitarianism depends on what sort of modalist they are. If they think that the one God is a self, and that “Father,” “Son,” and “Spirit” name modes of that one divine self, then they do not agree that the one God is the same self as the Father, for they don’t think the Father is a self at all! Rather, something like a personality or mode of living – but in that case, they are not unitarians, but trinitarians (see the final definition in my last post). Ever heart of Barth or Rahner? Modalists? Yes. Sabellian modalists? No. Unitarians? No. (So, not Christian unitarians either.) Trinitarians? Yes. All as it should be.

Similarly, by this definition many evangelical Christians are unitarians (and also Christian unitarians), as they think that Jesus and the Father are one and the same self (and perhaps the Holy Spirit too). But again, this is correct – they are indeed unitarians (perhaps inconsistent ones, if they also agree to some trinitarian theory). This unitarianism is in fact bemoaned by many a trinitarian theologian – it is usually put as the complaint that many Christians are “practically unitarian.”

Finally, I note that I don’t see anything polemical here. Unitarianism is not being defined as the truly biblical view, or has correct, orthodox, etc. Neither is it being defined as mere Trinity-theory-denial or a view held by “cults,” etc. When it comes to inter-Christian disputes about “the Trinity,” both friend and foe should accept this definition of the concept of a unitarian, as well as this concept of a unitarian Christian.

I’ve defined, I hope rightly, the concepts unitarian and trinitarian – these define such people in terms of their beliefs. Equally well, we would have definitions of types of Trinity theories rather than types of believers; the corresponding “isms” would be:

- unitarianism: that the one God just is (i.e. is numerically identical to) a certain self and not to any other self.

- Christian unitarianism: that the one God just is (i.e. is numerically identical to) a certain self, namely the Father, and not to any other self.

- trinitarianism: that the one God in some sense eternally consists of three ontologically equal “persons,” namely, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Pingback: Defining the concept of a trinitarian (Dale) » trinities

Pingback: Defining the concept of a Christian unitarian (Dale) » trinities

They would be unitarians by definition 3, which I maintain is the best definition.

They would not of course be Christian unitarians.

Rather, they *should* not! Your question points out a problem with my definition of a Christian unitarian. The problem is that by “the Father” is meant the to whom Jesus referred using those words (and “my Father” “our Father” etc). But then, Abraham et. al. DID identify that being with the one God. But surely Abe was no Chrisitan.

OK, back to the drawing board – will try again with Christian unitarian etc. in my next post.

Thanks for busting my bad def of the concept of a Christian unitarian, Mike. It is too wide.

Do pre-Christian Jews (e.g. Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, Daniel) fall into your first or second unitarian category?

Comments are closed.