Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

The Social Trinity may be more social than you thought. In this episode I talk with trinities contributor Mr. Chad McIntosh, who we met in our last episode. We discuss his new twist on a “social” Trinity theory – that not only are there three divine persons or selves, but in another but related sense, the Trinity is a person, what he calls a functional person. So there are in his view four persons in the Trinity, three intrinsicist persons and one one functional person. It is commonly objected to three-self or “social” trinitarians, that on their views “God” is a mere group of selves or a composite object made of selves – something (emphasis on “thing”), an “it” and not a self, which isn’t the sort of being it makes sense to love and worship, and isn’t the sort of being who literally acts, knows, and loves. This objection is answered by Mr. Macintosh’s sort of social theory. He also explains why this theory provides a good answer to my divine deception arguments against social trinitarianism. In sum, he argues that this is no objectionable Quaternity.

The Social Trinity may be more social than you thought. In this episode I talk with trinities contributor Mr. Chad McIntosh, who we met in our last episode. We discuss his new twist on a “social” Trinity theory – that not only are there three divine persons or selves, but in another but related sense, the Trinity is a person, what he calls a functional person. So there are in his view four persons in the Trinity, three intrinsicist persons and one one functional person. It is commonly objected to three-self or “social” trinitarians, that on their views “God” is a mere group of selves or a composite object made of selves – something (emphasis on “thing”), an “it” and not a self, which isn’t the sort of being it makes sense to love and worship, and isn’t the sort of being who literally acts, knows, and loves. This objection is answered by Mr. Macintosh’s sort of social theory. He also explains why this theory provides a good answer to my divine deception arguments against social trinitarianism. In sum, he argues that this is no objectionable Quaternity.

Do you agree?

You can also listen to this episode on Stitcher or iTunes (please subscribe, rate, and review us in either or both – directions here). It is also available on Youtube (scroll down – you can subscribe here). If you would like to upload audio feedback for possible inclusion in a future episode of this podcast, put the audio file here.

Links for this episode:

- Mr. McIntosh’s blog Appeared-to-Blogly

- the concept of “family resemblance“

- the concept of a sufficient condition

- the concept(s) of intrinsic nature (aka essence, essential properties)

- deception arguments against a three-self Trinity

- This week’s thinking music is “Anchor” from the album Ashes by Josh Woodward.

- You can now easily access all episodes of the trinities podcast in order here.

Pingback: Yet More Theories of the Trinity - Trinities

This episode has given me a new glimpse about what may have happened to trinity in modern charismatic churches, and also expressed in the worship these churches compose.

Chad McIntosh has this rather out-there idea, which I am beginning to think is actually making some very real sense to me, about God as a person (his main work that he will publish, and I will definitely get, is called “God of the Groups”). His point is that really a lot of church faith, in practice, works itself out as God is a person, not three persons. And McIntosh’s point is that this is entirely possible because there are intrinsic persons, and functional persons.

Intrinsic persons, as we would usually imagine them, including people who have absolutely no brain activity on life-support etc.

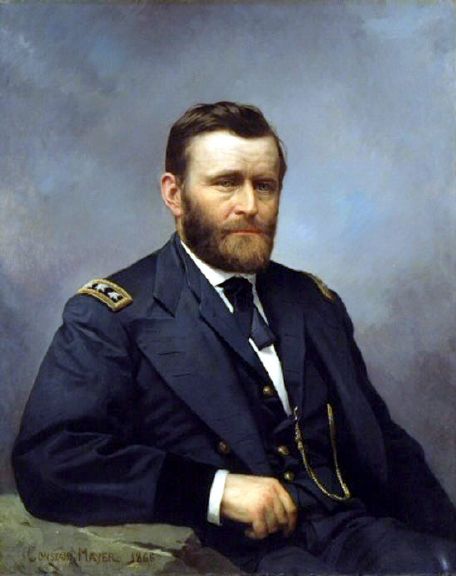

Functional persons, e.g. a group spoken of as a person, such as a general (“Grant”) who sent his platoon out against the enemy, but McIntosh says “it would make sense to say that “Grant had a bad day”” referring to the squad that got annihilated.

Where I felt McIntosh needed to be a little tighter I felt was on the Personhood criteria, morally responsible, free will, self-conscious (how is a foetus self-conscious?). But, basically, he argues that some non-intrinsic persons, like groups, robots too, could satisfy some of the key personhood criteria, in a way that (both Tuggy and McIntosh clarify this) is non-cumulative with intrinsic persons.

So, as some know, I have been finding the worship and focus of charismatic church to be highly Jesus-focussed at the expense of the Father (or rather Christians’ access to the Father) in particular, even though he is the one that is most clearly and explicitly identified in the New Testament as God, and even by Jesus, in John’s own memory (e.g. “I am ascending to my father and your father, to my God and your God”). I definitely do not think that this is something unique to my church! For a time I had been thinking that what was essentially being practiced was a kind of functional unitarianism; the trinity collapsed into Jesus, the second person. Yes we profess when pushed the Trinitarian position, with some occasional Fatherhood of God teaching and worship, but basically, Jésus, sois le centre. (I am part of a French charismatic church in Marseille; this morning we sang about “Jesus’ house” a.k.a my Father’s house has many rooms, Jesus’ paternity, etc, etc, etc.)

BUT, what I am now wondering, is with McIntosh’s view of a group being identifiable as a person, if actually what is happening is that we have named the group of co-eternal co-equal consubstantial persons, “Jesus”, in charismatic circles I mean. This would be me trying to recognise a truer and firmer triune focus to who we are and what we believe as a charismatic evangelical church, and our attempt to live that out in a way that human beings are kind of pre-programmed to have relationships, that persons around me are persons and that the one God – for us to have a relationship with him – must be a person.

Hi Rob,

My understanding of Hebrews 1:7-8 and Hebrews 1:10-13 is that the “and” in Hebrews 1:7 goes with the “but” in Hebrews 1:8. Likewise, the “and” in Hebrews 1:10 goes with the “but” in Hebrews 1:13 because Paul is drawing two contrasts showing that Jesus Christ (“the son”) was given authority superior to the angels.

I think both “O God” (lit. “the God”) in Hebrews 1:8 and “You Lord” in Hebrews 1:10 were both referring to God the Father because the word “God” appears again twice in Hebrews 1:9 and refers to the Father, and the writer attributes “the works of Your hands” (Hebrews 1:10) to the Father again in Hebrews 2:7.

You’ll find your understanding reinforced in the video.

Rivers,

Let me change my recommendation slightly and say that the Youtube video “Hebrew 1:7 & the Failure of Trinitarian Academia” should be the first one watched. Here a fundamental point of structure for Hebrews 1 is pointed out in great detail. Without the step-by-step visual demonstration of this obvious (after seeing it) structure, the details of the 8 part serious are harder to comprehend. So start here, and please post if you find this as compelling as I do. I consider it a real interpretational masterpiece. http://youtu.be/ytgWiK0HVro

I just finished this video. I think this guy makes some very good points. I also think that he makes a couple of mistakes which, if I could state briefly would be as follows:

1. He seems to not be familiar with the view of the NT writers that what scripture says, God says. God does not have to be the speaker in the OT for a NT writer to say “He (God) says.”

2. He thinks the immediate OT context should be used in a way to shape how he interprets the NT which sometimes leads to an incorrect understanding of what the NT writers meant or were thinking.

Hi Aaron,

Is there any way you could be more specific about where you think these mistakes are being made in the context of Hebrews 1:7-13?

For example, I would argue that “O God” (lit. “the God”) in Hebrews 1:8 refers the the Father because that is who “God” is throughout the context (Hebrews 1:3, 9).

I would also argue that “You Lord” (Hebrews 1:10) also refers to the Father because that is Who the writer identifies with “the works of Your hands” in Hebrew 2:7.

Thus, I don’t think it’s necessary to appeal to anything outside of the context of Hebrews 1-2 in order to explain what the writer intended by quoting the texts from the Hebrew scriptures.

Hey Rivers,

Thanks for engaging me about this. Well I want to first say that I don’t think one has to be Trinitarian to disagree with some of what he is saying or even the whole thing. That the writers of the NT are flexible in saying that what scripture says = what God says is pretty self-explanatory. I doubt many would disagree with it. We know that in other places David might have been the speaker but it says later on that “God” said this or that. The opposite is also true. At times God is the speaker in the OT but the NT author attributes the quote to the OT writer. Consider how Isaiah 65:1 is quoted in Romans 10:20. No one gets upset that Isaiah is being attributed these words despite the fact that he technically wasn’t the speaker in the original context.

Now, building on this point from above, let’s look at when he says we should translate the Greek as “it says” and not “he says.” Notice that he says later that there should be an antecedent for the pronoun “he” in verse 13. But why doesn’t he require there to be an antecedent for “it” in all the other verses? Don’t you think this is grammatically inconsistent? The only antecedent in Hebrews 1 is “God” so based off his reasoning “he says” is more justified than “it says.” (Note: I am not arguing this as my reasoning for translating it one way or the other, I am just trying to show the inconsistency in his logic.)

Lastly, he is forcing the context of Psalm 45 of the wedding of the Davidic King on the NT text. We know that NT writers don’t always care about what the OT text was saying in its original context. Consider Matthew’s quote of Hosea 11:1, “Out of Egypt I called my son.” The original context is talking about the nation of Israel, not Jesus. So what I am saying is that there is no reason to assume that the NT writers can’t take something typological from the OT and apply it to Jesus in a new way. This leaves open the door for us to read the passage in a way which could ascribe the word “God” to the Son.

I thought the stronger points of his presentation were the difference in the 2 Greek words when he translated it “it says” VS when he said God was actually speaking as well as the proposing the 3 “and/but” arguments which he thought the author of Hebrews made. So, good stuff, but not without weaknesses from what I can tell. Either way, I don’t think Trinitarianism or Unitarianism hinge on this one passage though.

“…there is no reason to assume that the NT

writers can’t take something typological from the OT and apply it to

Jesus in a new way.”

That astute observation should be framed and hung in the study of all who seek to understand the NT’s presentation of Christ!

“This leaves open the door for us to read the passage

in a way which could ascribe the word “God” to the Son.”

IMO, Heb 1:8 is either calling Jesus God or saying that God is his throne, and I favor the former.

~Sean

Sean,

Your suggestion that the meaning of “Your throne, O God” (lit. “the God”) in Hebrews 1:8 has only the options of referring to Jesus Christ or of saying that “God is a throne” is unwarranted.

For example, it makes perfectly good sense if Hebrews 1:8 simply refers to the “throne” of “God” the Father. Jesus was teaching that his “throne” is the same as the “throne” of the Father (Revelation 3:21).

I did say “IMO,” remember;-) I wasn’t ruling out other possible understandings, but was merely stating what I think are the probable choices.

Hi Aaron,

I think you’ve made a lot of good points. I definitely agree that the apostles didn’t always derive their application of the Hebrew scriptures using a grammatical-historical approach. Sometimes they applied things to Jesus Christ that one wouldn’t anticipate from the plain reading of the passages in their original context.

Thus, I agree that the original context of Psalms 45 may not be the critical factor in determining why the writer of Hebrews applied the passage to Jesus Christ. That is why I still favor interpreting “O God” (lit. “the God”) in Hebrews 1:8 as a reference to the same “God” who is mentioned in Hebrews 1:3, 9 rather than depending upon a particular interpretion of the Psalm. With that said, I’m not sure that the original reference to “God” in Psalms 45:6 is referring to the Davidic king either.

Yes, I do think the development of the “and/but” arguments is important in the context of Hebrew 1. I think it would be difficult to sustain the idea that the purpose of any of the language in this passage was intended to prove that Jesus is “God.” I think it’s evident that his superiority to the angels is all that is in view, and the writer plainly used “God, your God”(Hebrews 1:9) to reiterate the distinction between the authority of the Father and the son.

BTW, I should add that I don’t have much patience for conspiracy theories. I think the argument that Jesus is called “God” at Heb. 1:8 in most Bibles because of “Lies” is unconvincing in the extreme. I’m not a Trinitarian and I accept that Jesus is likely called hO QEOS there, just as I accept that an earthly king was likely called hO QEOS at Psalm 45:6. Why seek to avoid such an application?

Sean,

I agree. I also think “lies” is a bit too strong. It’s understandable that someone who has options in translation would favor the one that seems consistent with his own theological viewpoint.

I would expand on that and say that it’s understandable that someone would favor a rendering that seems consistent with his theology, his view of context, and his view of historical probability.

B.F. Wescott was no Unitarian, yet he favored “God is your throne,” in light of grammar and in light of such additional considerations. I think his primary reason — i.e. that Jews couldn’t have referred to a king as God (i.e. at Ps. 45) — was mistaken in light of what we know about the application of divine titles to agents of God in Jewish writings.

Sean,

Good point. Even though I would be considered a biblical unitarian, I don’t think a lot the “agency” arguments that other unitarians use are significant or necessary at all.

The apostles spoke of Jesus Christ as “the Christ and the son of God” (John 20:31). This was sufficient to identify him as one sent from God the Father. I don’t think the “divine agency” issue was ever a point of debate for them.

The idea of being “equal with God” (John 5:18; Philippians 2:6) was a matter of being the Father’s “heir” who “owns everything” (Galatians 4:1-2; John 17:5) and not about being a divine representative or messenger.

The point of divine agency was taken for granted. It was an integral part of the culture, and calling Jesus the Messiah/Son of God was to call him an agent of God.

Sean,

I don’t think the “agency” idea makes any difference. If being called Messiah or son of God was only a matter of agency, then it would mean that Jesus Christ was no more important than any of the angels, Patriarchs, kings, judges, or prophets, who appeared before him.

Rather, the apostles specifically came to know Jesus as “the Christ and the son of God” on account of the “signs” that he performed (John 20:31) and the miracle of his resurrection (Acts 2:29-36). These were the things that identified him as “the only begotten.”

Yes, you’ve expressed that opinion a number of times, and I not only don’t find it compelling, but I find that it suggests a rather remarkable lacuna in your approach. Everyone on the planet whose studied agency sees it at work in the NT, and most especially in John. I think you just like to be different.

FYI, there’s an interesting article about divine agency in John, here:

https://www.academia.edu/11558065/_The_Having-Sent-Me-Father_Aspects_of_Agency_Encounter_and_Irony_in_the_Johannine_Father-Son_Relationship_

The agency paradigm is so clearly at work in the NT’s presentation of Christ — and particularly so in John — that for one to miss it would seem to indicate lacunae in one’s exegetical methodology.

Yes Sean, I agree. And I think as well that it should be noted that everyone, Trinitarian or not, has to deal with the fact that this same passage which calls Jesus “God” also says, “Therefore God, your God, has anointed you…” This, as well as other verses where Jesus says the Father is “His God” mean that whatever Christology we have we have to try and see how Jesus logically can have the Father as His God. This is without a doubt more complex for Trinitarians than the various Unitarian positions.

I think it’s interesting that when we find Jesus either referred to as God or supposedly “equal with God,” the context typically is not what one would expect if the writer thought that Jesus was the one God of Jewish monotheism. When divine titles or exclamations of absolute authority are applied to God himself there is no qualification, but when they’re applied to Jesus there usually is.

Aaron,

The fact that “the God” is used twice to refer to the Father in the immediate context (Hebrews 1:9) when the writer is speaking of the “annointing” (Hebrews 1:9) of “the son” (Hebrews 1:8) makes it unlikely that “O God” (lit. “the God”) would be referring to Jesus Christ at all.

Moreover, the writer of Hebrews uses “the God” (O QEOS) dozens of times throughout the rest of the letter and it always refers to God the Father. Thus, there is no reason to think that Hebrews 1:8 is any exception. Rather, “Your throne, O God” is just a parenthetical reference to the throne of God the Father to which Jesus Christ was appointed.

I’d have to disagree with that. The text states “But of the Son (he/it says), “Your throne, O God…” I think this is just the plain reading of the text to acknowledge that “God” is here applied to Jesus. This doesn’t have to mean the writer was calling Jesus “God” in the absolute sense. Seeing that this is a verse which was originally said to a Davidic King it makes sense that it is now being applied to Jesus who is the ultimate Davidic King. It wasn’t calling the original Davidic king “God” in the highest sense so of course one could make the argument that it’s not doing that here either. Trinitarians will typically say that it is but I myself don’t think it has to be.

Quite so, and, IMO, the flow of the dialogue stronly suggests that God is speaking to the Son in verse 8, which negates the purported “lie” motif. Translators are simply taking context into consideration.

Hi Aaron,

I also had the tendency to assume that the antecedent of “Your throne, O God” (Hebrews 1:8) was “the son” and that it was the natural way of reading the text. However, here are a few things I had to reconsider in the context:

1. The “You Lord” in Hebrews 1:10 refers to God the Father (see Hebrews 2:7). This shows that the writer did not necessarily intend the “your” to be taken as a reference to the antecedent (the son) when he quoted these texts from the Hebrews scriptures. See also Hebrews 2:6-8.

2. The writer attributed “the throne” to God the Father elsewhere in the letter (Hebrews 4:16; Hebrews 8:1; Hebrews 12:2), and understood that Jesus Christ did not attain to the throne until after his resurrection (Hebrews 1:4; Hebrews 12:2).

3. The Greek is literally “the God” (HO QEOS). It is the usual definitive way the writer spoke of “the God” as the Father dozens of times (Hebrews 1:3; Hebrews 1:9, etc.) and is it is not necessary to make an exception by applying it to Jesus Christ in Hebrews 1:8.

“The fact that “the God” is used twice to refer to the Father in the

immediate context (Hebrews 1:9) when the writer is speaking of the

“annointing” (Hebrews 1:9) of “the son” (Hebrews 1:8) makes it unlikely

that “O God” (lit. “the God”) would be referring to Jesus Christ at all.”

That’s not a compelling argument, Rivers. The OT, the DSS, and Philo use God of the Father many thousands of times, but that doesn’t stop those writers from applying the title to agents of God, such as Moses, angels, kings, Melchizedek, etc. At Psalms 82 Hebrew terms for God/gods are used of both God and of judges in the very same sentence. If God can address a group as gods then he can certainly address one of them as God if he chooses to do so.

Sean,

I don’t think appealing to how Philo, DDS, or the Hebrew scriptures used the word “god” is of any significance at all when interpreting the meaning of “Your throne, the God” in the context of Hebrews 1:8-9. There’s no indication that the writer of Hebrews wasn’t capable of speaking on his own terms.

I think it is more significant to consider how the writer himself always used ‘O QEOS (“the God”) to refer God the Father dozens of other times throughout the letter (including Hebrews 1:1, 9 in the immediate context). I think it’s likely that the writer was making a point about the eternal duration of the Father’s “throne” (Hebrews 8:1; Hebrews 12:2) and not using “the God” to refer to the son.

Heb. 1:8 “Your throne, O God…” Here’s a video (shorter than the one on Heb. 1:7 ) 🙂 that looks at whether “O God” is a viable translation–very helpful, I think. http://youtu.be/oAOR2k-golw

On the contrary, it is clearly significant that in the Hebrew Scriptures, DSS, and Philo (and Midrashim), we find authors who almost exclusively reserve divine titles used in a positive way to the one God of Jewish monotheism, yet under the right circumstances will apply such titles to agents of God. Even more significant are the contexts in which such applications are deemed appropriate (e.g. those commissioned to speak for God, such as Moses, those commissioned to sit on God’s throne, such as kings, and those commissioned to carry out God’s will in the eschaton, such as Melchizedek), most of which also apply to Jesus in an even greater way!

It is also interesting that the Psalms, which the author of Hebrews used to build his argument, is one of the places where we see divine titles applied to individuals other than God. Would such an author be reluctant to apply the sorts of divine titles that were applied to lesser agents of God to the one whose hyper-exaltation he was determine to establish? Hardly!

Sorry, Rivers, but, as far as I’m concerned, your argument against the rendering that has the greatest support among translators just isn’t compelling.

Sean,

It’s a common exegetical fallacy (especially among scholars) to transfer authority outside of the context of a writer’s own use of vocabulary. Forcing the “divine title” idea into Hebrews 1:8 is also presumptive. These are the reasons that I don’t find that idea persuasive at all.

Yet it’s not an exegetical fallacy to allow writers to speak in the contexts of their time and place in history, and such contexts make it unlikely that the author of Hebrews would be at all reluctant to call Jesus God. Indeed, as I’ve said before, in light of the application of divine titles to agents of God in pretty much all forms of writing that existed around the time the NT was written, and in light of the contexts in which such applications were deemed appropriate, it would be downright shocking to find that such titles were NOT applied to Christ.

That you don’t find that persuasive is fine by me.

Sean,

The problem you have is that you don’t have any evidence of corroboration. Thus, all you are doing is making a fallacious appeal to external influences because you can’t come up with any exegetical or contextual reason that your interpretation is necesssary in the context of Hebrews 1:8-10.

All I’m suggesting is that the “divine agency” idea is not needed to explain anything in Hebrews 1-2. The writer was arguing that Jesus had a higher position of authority than the angels. There is no indication that “divine agency” had anything to do with his argumentation. Thus, supposedly calling Jesus “O God” in Hebrews 1:8 would have no purpose there.

And you are welcome to your opinion, misguided as it is:-)

Rivers,

I would reply more thoroughly but I think Sean has pretty much summed up what would be highly reflective of my view. What you’re saying seems akin to me saying that the author of Exodus uses “elohim” to refer to the God of Israel dozens of times, therefore attributing the term “elohim” to Moses in Exodus 7:1 is forced, unnatural and unwarranted. Forgive me for being frank, but that just seems silly.

Aaron,

I think the Exodus issue is different because there is evidence that ALHYM is being applied to beings other than YHWH in that context (as well as throughout the rest of the Hebrew scriptures). However, this is not the case in the context of Hebrews 1 (which can stand on its own).

Throughout the context of Hebrews 1-2 there is a consistent distinction between “the God” and “the son.” It couldn’t be more evident than it is in Hebrews 1:9 where it refers to the Father as “the God, your the God …” That is why I think it is likely that “the God” refers to the same person in Hebrews 1:8 as well.

Rob,

Yes, context is always the most important thing (and paying attention to the way a writer uses his own words). Ultimately, I think the contextual arguments are much stronger than the tendency of many scholars (including Buzzard) to appeal to the presupposed influence of external sources or to put an unnecessarily narrow emphasis on minute details of grammar in certain texts

.

Rob,

I’ve also found some of Anthony Buzzard’s research and argumentation to be limited and a bit outdated. However, I admire him for the effort he has made to promote biblical unitarianism. Many people have benefited from his debates and publications.

I agree that Sir Anthony has done a tremendous amount of valuable work. On the treatment of the issues in Hebrews 1, however, I find the presentations I refer to more comprehensive and convincing than anything I’ve yet seen. And all he really does is pay careful attention to the words, context, and author’s obvious intentions in order to demonstrate that the Trinitarian interpretation is a serious misunderstanding of the whole passage. I don’t think anyone who takes the time to watch these will be disappointed.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=FgVxqXAu8OA

3 – Hebrews Chapter One: Representation of God’s being

(And other Hebrews 1 videos at this site)

The Trinitarian fallacy of equivocation is discussed in this part of a series of Hebrews 1 discussions. All this author’s presentations on Hebrews 1 are very insightful. I think he demolishes the claim that Hebrews 1 calls Jesus LORD (YHWH), and does so in a more convincing way than Sir Anthony Buzzard did when challenging James White on this topic. Besides this 8-part series on Hebrews 1, search through the other videos on Hebrews. 1:7, 1:8, 1:10, etc.–VERY thorough and convincing! https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=FgVxqXAu8OA

3 – Hebrews Chapter One: Representation of God’s being

Dale,

I would like to know where Chad gets his exegetical basis for distinguishing a “being” from a “person” or “persons.” It seem like he is starting with the presuppositional conceptual idea that a “being” can be defined in terms of multiple “persons” without any reason to think that any of the biblical writers would have conceived of that kind of relational identity or even been able to express it in the limited vocabulary of the ancient languages (which have no words to distinguish between “being” and “person”).

This is a good discussion on whether the one God of 1 Cor. 8 is a person: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=aP7MQh7gQNY

1 Corinthians 8:6 & the Trinitarian Blunder

Comments are closed.