Congratulations to both debaters on a fight well fought. (Here’s all the commentary.) Plenty of punches, thrown hard, relatively few low blows – two worthy opponents. Certainly, the fight must be decided on points, as there was no decisive knockout. Both debates are in different ways very impressive, and I learned a lot from both.

Congratulations to both debaters on a fight well fought. (Here’s all the commentary.) Plenty of punches, thrown hard, relatively few low blows – two worthy opponents. Certainly, the fight must be decided on points, as there was no decisive knockout. Both debates are in different ways very impressive, and I learned a lot from both.

Kudos to C. Michael Patton and Parchment and Pen for hosting the debate.

I hope you readers out there enjoyed my commentary on the debate. I sometimes got naggy or nerdy, and always expressed myself with typical lack of tact, but I tried to be helpful, and to show the helpfulness of philosophy and logic in thinking through these things.

In this last post in the series, a few concluding reflections on the debate.

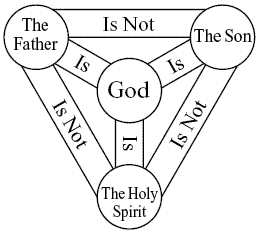

Looking back on this debate, I see that I’ve ended up where I began: wondering what Bowman thinks the Trinity doctrine is. This, after all the debate was about whether or not the Bible teaches that.

Burke argued that the Bible teaches what I call humanitarian unitarianism (he calls it “biblical unitarianism”) – roughly, that the one God of Israel is the Father, whereas the Lord Jesus is a human being and his unique Son, and the Holy Spirit is God’s power. I understand what Burke argued for, and if it is true, then nothing that can claim to be an orthodox Trinity theory is true. But I don’t, in the end, understand Bowman’s view.

I flagged this issue at the start. As the debate wore on, I settled on the interpretation that each of the Three just is (is numerically identical to) God, and yet each of the three is not identical to either of the other two. I stuck with this interpretation, all the way to the bitter end. And yet, I never did like this interpretation Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – Final Reflections

Three World Vision employees

Three World Vision employees

Were there any “biblical unitarians”, or what I call humanitarian unitarians in the early church?

Were there any “biblical unitarians”, or what I call humanitarian unitarians in the early church?

As I explained

As I explained

In

In