Has Richard, after these 21 chapters so far of Book III of his On the Trinity (De Trinitate) only succeeded in proving that there are at least three gods? In chapter 22, Richard argues for a negative answer.

Has Richard, after these 21 chapters so far of Book III of his On the Trinity (De Trinitate) only succeeded in proving that there are at least three gods? In chapter 22, Richard argues for a negative answer.

First, he refers back to the doctrine of divine simplicity, which is common coin for medieval theists, even, surprisingly, for trinitarians. This needs explaining nowadays – theists now tend to think of God’s nature as something he has, and of God as having, and not being, his attributes. Moreover, we tend to think that God has many attributes.

For a primer on divine simplicity, I can do no better than Bill Vallicella:

[According to this doctrine] God is radically unlike creatures in that he is devoid of any complexity or composition, whether physical or metaphysical. Besides lacking spatial and temporal parts, God is free of matter/form composition, potency/act composition, and existence/essence composition. There is also no real distinction between God as subject of his attributes and his attributes. God is thus in a sense requiring clarification identical to each of his attributes, which implies that each attribute is identical to every other one. God is omniscient, then, not in virtue of instantiating or exemplifying omniscience — which would imply a real distinction between God and the property of omniscience — but by being omniscience. And the same holds for each of the divine omni-attributes: God is what he has. As identical to each of his attributes, God is identical to his nature. And since his nature or essence is identical to his existence, God is identical to his existence. (William Vallicella, “Divine Simplicity”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

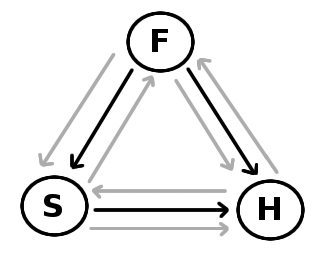

Richard starts ch. 22 by gesturing back at book I of De Trinitate – his point is that this divine being/essence/nature common to the three is utterly simple. Yet he realizes that this by itself won’t soothe the concern about monotheism. How can we rule out that there are three gods, each of which has is an utterly simple, composition free being? Then he hits on an additional argument.Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 22 – part 1

Last time I tried to analyze Richard’s argument in ch. 22 that his view preserves monotheism. This time, I critically evaluate the argument. Is it sound?

Last time I tried to analyze Richard’s argument in ch. 22 that his view preserves monotheism. This time, I critically evaluate the argument. Is it sound?