podcast 158 – Listener Questions 3

An appealing theological option which is neither Nicene nor “Arian”?

An appealing theological option which is neither Nicene nor “Arian”?

If you suffer from this affliction, I recommend repeated listens.

Devastating. I have long noted that Augustinian/Calvinist theology is unpopular among Christian philosophers, though many, like me, go through a Calvinist phase (when I was a sophomore and junior in college), before seeing its problems to be hopeless. Walls concisely and fairly sums up what Calvinism is all about, and then shows it to be profoundly problematic, focusing on philosophical problem rather than biblical ones.… Read More »Jerry Walls: What is wrong with Calvinism?

Many of you know that I’ve argued in several ways, in print, against “social” Trinity theories, and particularly the sort which holds that Father, Son, and Spirit are a group/community/quasi-family. On such theories, it turns out that the one “God” is a group – a group of equally divine selves (aka gods – though they don’t like that term in the plural). This is surprising… Read More »Is God a self? Part 1

Last time we briefly explored Redirection, the first of our four ways to respond to apparent contradictions in theology.

The response of Restraint is a little more reasonable. This person realizes that a certain way of understanding, say, the doctrine of the Trinity, seems inconsistent. The Christian walking the path of Restraint declines to endorse that way of understanding the Trinity, or any other clear formulation. “Sure, if it meant X, then it would seem contradictory… but maybe it doesn’t mean X.”

The Restrained believer neither affirms nor denies X, exercising Restraint . He declines to say precisely what the great Doctrine in question is, because (he says) he doesn’t know what it is supposed to be. Read More »Dealing with Apparent Contradictions: Part 3 – Restraint (Dale)

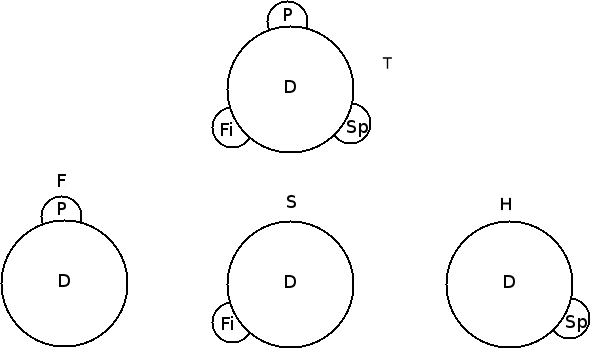

Here’s a second application for my Latin Trinity chart (see the first post for what the letters designate). Let’s say that a state of affairs is a thing/substance having a property at a time or timelessly.

The “persons” here are just modes of D, that is, states of affairs involving D. So the Son just is D having Fi. And the Father just is D having P. And the Holy Spirit just is D having Sp. Regarding each of F, S, and H, each of them “just is” D – in the sense that in each of them, there is one and the same D.Read More »The Latin Trinity Chart 2 – a version of FSH modalism

The traditional Christian doctrine of the Trinity is commonly expressed as the claim that the one God “exists as” Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or as the claim that there are three divine persons “in” God, or as the claim that God “exists in three Persons”. I have to say: this drives me nuts. The “exists as” formula strongly suggests modalism, the idea that Father,… Read More »“the” Trinity doctrine – Part 1

Dialogue with an apologist about changes of tritheism and “the doctrine of the Trinity.”

What, precisely, is “modalism,” and what, if anything, is wrong with it? I find the theological and historical literature to be depressingly unclear about this. Why? Partly it’s the sparseness and obscurity of the original sources. Partly it’s the habit of simply repeating the same lore over and over, couched in the same (sometimes unhelpful) terms, starring the same (not too well drawn) heroes and… Read More »What is Modalism?

In De Trinitate Book 3.7 Richard summarizes some of what comes beforehand. We have learned that supreme goodness requires supreme love (i.e. supreme love is a necessary condition for supreme goodness), and that supreme love requires more than one person. If supreme love were only self-love, then the total state of affairs “one divine person has self-love” is not as perfect a state of affairs as another total state of affairs, namely “two persons have self-love, and each loves the other person.” Thus,

If there is supreme love, then there is a plurality of persons.

Likewise, Henry infers from what he takes to be the nature of supreme love to entail the equality of the persons in question.

If there is supreme love, then there is an equality of persons.

Below I try to explain just what all this means.

Read More »Richard of St. Victor 6 – Supreme Love Only Among Equals, Again (Scott)

In the last three posts, I explained Richard’s argument for why there must be two distinct persons who charitably love each other. Here I want to raise some objections to three of Richard’s claims.

Read More »Richard of St. Victor 5 – Evaluation of the argument thus far (JT)

STAGE 3. Next, Richard tries to establish that God can only charitably love an equal. He introduces this idea by raising the following objection: if God must direct his charitable love at a distinct person, then why couldn’t he direct his charitable love at a created person? That would satisfy T5 from the last post, so that should be enough to perfect God’s charitable disposition, right?

Read More »Richard of St. Victor 4 – Charity is shared by equals (JT)

STAGE 2. In this stage, Richard tries to show that perfect charity must be directed at another person. Here’s the quotation:

‘no one is properly said to have charity on the basis of his own private love of himself. And so it is necessary for love to be directed toward another for it to be charity’.

Read More »Richard of St. Victor 3 – Perfect charity must be directed at another person (JT)

STAGE 1. In this stage, Richard wants to show that God’s perfect goodness somehow requires that God is perfectly charitable. I say ‘somehow requires’ because the logical relation here is not clear. Richard is saying ‘God’s goodness _____ perfect charity’, but what fills in the blank? Is it ‘entails’, ‘presupposes’, or some other logical relation?

Here’s the actual quotation, with the particular claims marked in brackets.

‘[T1] there is [in God] fullness and perfection of all goodness. [T2] However, where there is fullness of all goodness, true and supreme charity cannot be lacking. [T3] For nothing is better than charity; nothing is more perfect than charity’.

Let’s look at T1, T2, and T3 in turn.

Read More »Richard of St. Victor 2 – God’s goodness requires charity (JT)

Richard of St. Victor is well known for his argument that perfect love must be shared between three persons, and since God’s love is perfect, there must be three persons in God. Richard presents this argument in Book 3 of his De Trinitate, and that’s what we’ll be looking at in this series of posts.

Is this “beginning” when the cosmos was created by God, or when it was “newly created” through the man Jesus?