Search Results for: orthodox formulas

podcast 372 – Book Session Identity Crisis – Part 1

Four authors summarize their views on the Trinity.

You’re another!

“You’re another” – that’s what tu quoque means – it’s the name of an informal fallacy, often called a fallacy of relevance. For example, if I argue that your theory is self-contradictory, suppose you retort that my theory is too. Well, so…? It’s irrelevant to the point that the first theory mentioned is self-contradictory (so, self-refuting).

“You’re another” – that’s what tu quoque means – it’s the name of an informal fallacy, often called a fallacy of relevance. For example, if I argue that your theory is self-contradictory, suppose you retort that my theory is too. Well, so…? It’s irrelevant to the point that the first theory mentioned is self-contradictory (so, self-refuting).

Cornell grad student Chad McIntosh argues that if the social trinitarian God – or rather: the three divine persons posited by clear “social” Trinity theories – would be deceivers, then so would the perfect self in whom I believe, being a unitarian Christian. So granting that an ST is implausible, for similar reasons unitarian Christian theology is implausible (because it has a perfect being doing what appears a wrongful deception).

Is this a defense of ST?

I’ve already argued in that paper than a Swinburne-type ST implies what looks like wrongful deception by at least one of the three divine persons. This hasn’t been disputed.

I don’t grant that if God is a single self, then Read More »You’re another!

“Sabellianism Reconsidered” Considered – Part 7 (Dale)

Time for the old Spanish Inquisition. Will she survive The (self-administered) Rack?

Time for the old Spanish Inquisition. Will she survive The (self-administered) Rack?

In the final part of her article “Sabellianism Reconsidered”, Baber turns to theological objections. To wit:

- The account renders it impossible for the Son to pray to the Father. But the NT says this happened.

- The account denies that each Person of the Trinity is himself eternal, and has eternally born relations to the other two Persons. (pp. 8-9, paraphrased)

Her answers? Jesus, like his contemporaries, was not a trinitarian. That is, he didn’t realize that the God to whom he prayed had temporal parts which were gods. Or even if he did, he didn’t intend to teach any trinitarian doctrine. Thus, he addressed not the Father, but God, as “Father”. (p. 10) Thus the term “Father”, in Jesus’ context, referred to God, while nowadays (post 380 CE?) it refers to the Father, the (temporally) first Person of the Trinity.

In response to the second objection, she notes that “a notion of timeless, metaphysically necessary causationRead More »“Sabellianism Reconsidered” Considered – Part 7 (Dale)

Dealing with Apparent Contradictions: Part 3 – Restraint (Dale)

Don’t ask me what this doctrine means… I only believe it.

Last time we briefly explored Redirection, the first of our four ways to respond to apparent contradictions in theology.

The response of Restraint is a little more reasonable. This person realizes that a certain way of understanding, say, the doctrine of the Trinity, seems inconsistent. The Christian walking the path of Restraint declines to endorse that way of understanding the Trinity, or any other clear formulation. “Sure, if it meant X, then it would seem contradictory… but maybe it doesn’t mean X.”

The Restrained believer neither affirms nor denies X, exercising Restraint . He declines to say precisely what the great Doctrine in question is, because (he says) he doesn’t know what it is supposed to be. Read More »Dealing with Apparent Contradictions: Part 3 – Restraint (Dale)

“the” Trinity doctrine – Part 1

The traditional Christian doctrine of the Trinity is commonly expressed as the claim that the one God “exists as” Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or as the claim that there are three divine persons “in” God, or as the claim that God “exists in three Persons”. I have to say: this drives me nuts. The “exists as” formula strongly suggests modalism, the idea that Father,… Read More »“the” Trinity doctrine – Part 1

banning the word “trinitarian”

Thanks to reader Mike K. for this hilarious link. They beat me to the punch – I’ve been sitting on a post for some time on this exact theme. (Stay tuned.) I posted a comment asking about this bit: It’s interesting to note that the English term “Trinitarian” was first used, in the 16th and 17th centuries, as a pejorative description of anti-trinitarians; the heretics… Read More »banning the word “trinitarian”

Are all religions the same?

I have been working through Alvin Plantinga’s excellent (but frustrating) book Warranted Christian Belief, and I am particularly intrigued by his critique of the work of theologian John Hick. Hick began his spiritual odyssey as a traditional, orthodox Christian, accepting what I have been calling ‘Christian belief’. He was then struck by the fact that there are other religions in which the claims of orthodox Christianity—trinity,… Read More »Are all religions the same?

10 steps towards getting less confused about the Trinity – #1 Who’s to say? – Part 2

Plausibly, most Protestant scholars who think that the Bible teaches the Trinity focus on the New Testament. They argue that while trinitarianism isn’t explicit there, it is implicit.

podcast 242 – Dr. Beau Branson on the Monarchy of the Father – Part 4

A summary of Dr. Branson’s case and an argument against biblical unitarian theology.

yet more on Modes and Modalism: Barth and Letham

I’ve been reading Robert Letham’s The Holy Trinity lately. He’s a Reformed kind of guy, and like many contemporary theologians, he’s spent a lot of time thinking about Karl Barth. Now it’s well known that Barth in many places denies that he’s a “modalist” about the Trinity, and yet he says many things like these (these are quoted from Barth’s works by Letham): God is… Read More »yet more on Modes and Modalism: Barth and Letham

SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 1

In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

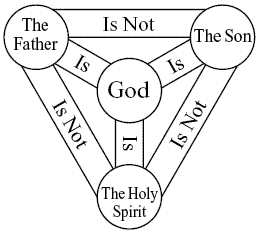

In the preceding three rounds of this debate, I have argued that the person of Jesus Christ existed as God prior to the creation of the world and that the Holy Spirit is also a divine person. If my argument up to this point has been successful, I have thoroughly refuted the Biblical Unitarian position and established two key elements of the doctrine of the Trinity. Add to these two points the premises that there is only one God who existed before creation and that the Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, and the Father is not the Holy Spirit, and the only theological position in the marketplace of ideas that is left is the doctrine of the Trinity. Since these are all premises that Biblical Unitarianism accepts, I have not defended them here. (emphases added)

I’m tired of pointing out the inconsistency of what Bowman is urging. I’m capable of hearing the many ways theorists smooth away apparent inconsistencies (making subtle distinctions), but other than a quick gesture (I think in Round 1), I hear none of these familiar notes from him. This is just to say – he’s a resolute positive mysterian. Briefly, Father, Son and Spirit are numerically three, as they qualitatively differ from one another. But also, Bowman seems to think, each of them is numerically the same as God. This is inconsistent, because the “is” of numerical sameness is transitive – if f = g, and g = s, then f = s (compare: the concept of “bigger than”). Also, it seems that he thinks Father and Son to the same god, and also, since this god just is a person (hence “who” above), they are the same person as each other. And, of course, also they are not. Sigh. Let’s stick with the vague “threefoldness” claim I started with.

Bowman ignores what I call Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 1

too many Jesuses vs. too many “Jesuses”

Deciding to call just one of the three selves in your christology “Jesus” doesn’t fix the fact that your theory has two too many selves.

podcast 59 – Dr. Carl Mosser on salvation as deification

When a Christian is saved, is she thereby deified? This is how Eastern Orthodox theologians describe Christian salvation, and it is a common saying that this is distinctive of Eastern Christian theology, but not of Western. In this episode, Dr. Carl Mosser (Associate Professor at Eastern University, on leave, and a Visiting Scholar at the Center for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Notre Dame) challenges this assumption,… Read More »podcast 59 – Dr. Carl Mosser on salvation as deification

Islam-Inspired Modalism – Part 2

Last time we looked at an exchange between Christian and Muslim apologists in the early 14th century, in which the Christian side, under pressure from longstanding Muslim accusations of polytheism, spells out the doctrine of the Trinity in a plainly modalistic way. This practice is ongoing, as we’ll see. Thomas F. Michel is a Jesuit priest and scholar who edited and translated the largest response… Read More »Islam-Inspired Modalism – Part 2

A formulation of Leibniz’s Law / the Indiscernibility of Identicals

In discussing the Trinity or Incarnation, I often have an exchange which goes like this:

In discussing the Trinity or Incarnation, I often have an exchange which goes like this:

- someone: Jesus is God.

- me: You mean, Jesus is God himself?

- someone: Yeah.

- me: Don’t you think something is true of Jesus, that isn’t true of God, and vice-versa?

- someone: Yes. e.g. God sent his Son. Jesus didn’t. God is a Trinity. Jesus is not a Trinity.

- me: Right. Then in your view, Jesus is not God.

- someone: But he is.

- me: So, you think he is, and he ain’t?!

- someone: [silent puzzlement]

In this post, I want to explain the part in italics. First: a point of clarification. The second and third lines are important. When many say “Jesus is God” they just mean that in some sense or other Jesus is “divine.” (This could mean a lot of things, depending on one’s assumed metaphysics.) But this sort of person (line 3) understands Jesus to be “divine” in the sense of just being one and the same as God – that Jesus is God himself – one person, so just one (period).

In the italicized line, I’m applying something called Leibniz’s Law, or the Indiscernibility of Identicals. I sometimes put this roughly as, some x and some y can be numerically identical only if whatever is true of one is true of the other. That’s a sloppy way to put it.

In logic, a more precise way of stating it (used e.g. by Richard Cartwright) is:

(x)(y)(z) ( x= y only if (z is a property of x if and only if z is a property of y))

Literally: for any three things whatever, the first is identical to the second only if the third is a property of the first just in case the third is a property of the second.

The basic intuition is that things are as they are, and not some other way. So if x just is (is numerically the same as) y, then it can’t be that x and y qualitatively differ. This seems undeniable.

There are a few problems, though, with the above formula, which any person trained in philosophy may spot. Read More »A formulation of Leibniz’s Law / the Indiscernibility of Identicals

“Trinity” in paperback form

Suppose you want to really study my entry “Trinity“ in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. If you’re like me, when you want to really read something, you’ll print it out (and then proceed to destroy it with a pencil and a highlighter). And if you do print it all out, it’ll make your printer burst out in tears. The whole thing, with supplementary discussions, comes… Read More »“Trinity” in paperback form

Linkage: Vallicella and Lukas on Supposita

Thanks to Vlastimil Vohánka for referring us to this discussion between Maverick Philosopher Bill Vallicella and Dr. Lukas Novak of Charles University, Prague. As I understand it, a suppositum is supposed to be an ultimate subject of characteristics / properties, as distinct from non-ultimate subjects. My individual human nature is supposed to be suppositum, but Christ’s is not. One ought to be a little suspicious… Read More »Linkage: Vallicella and Lukas on Supposita

Don’t think/write like a contemporary theologian – Part 3 – tendencies

I have tendencies. Put me near a Subway restaurant, where I can smell the fresh bread, and I’ll get hungry, my mouth watering. Force me to watch reality TV shows, and I’ll become fatally bored. I have a tendency to smile in the presence of cute little kids. Doctrines do not have tendencies. They don’t do anything. They have meanings, and they stand in logical… Read More »Don’t think/write like a contemporary theologian – Part 3 – tendencies