“On Positive Mysterianism”

A paper on the rationality of believing apparent contradictions in theology.

A paper on the rationality of believing apparent contradictions in theology.

Congratulations to trinities contributer Scott Williams on the publication of his “Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Henry of Ghent, and John Duns Scotus: On the Theology of the Father’s Intellectual Generation of the Word”. His abstract: There are two general routes that Augustine suggests in De Trinitate, XV, 14-16, 23-25, for a psychological account of the Father’s intellectual generation of the Word. Thomas Aquinas and Henry of… Read More »Congrats on a Publication

A trinitarian facepalm for this, from a Bob Jones University Press grade school textbook (HT: Digg.) Not having seen the book, I can’t be sure what is going on here. Here are some options: The writer is terribly uninformed. The writer is feigning ignorance in a misguided attempt to instill delight and wonder into science. The writers is feigning ignorance in an attempt to multiply “mysteries”.… Read More »The Mystery of Electricity

Since I’m posting mildly entertaining nonsense lately, here’s a video from the, ahem, legendary Winterband. (Steve Winter, not Edgar & I assume, no relation), playing to a packed out basement (his own). Click if you dare.

Winterband is a power duo in reality, although Steve plays in three “persons”. (We must use this term, as we have none better.) Steve 1 plays lead and sings. Steve 2 plays rhythm. Steve 3 plays bass. And yet Read More »“You’re gonna burn, burn, burn, ’cause you would not learn.” (Dale)

Wasn’t expecting to find the Trinity on my late-night Walmart run! Actually, a pair of “trinities”, with co-equal prices. Decorating the mantle or end-table with religious statues has never been more affordable. I know you’re intrigued by these low, low prices. If you live in Tucson, Arizona, you might be able to get the last ones. I don’t know what the deal is with Jesus’ knee and calf.… Read More »a good deal on some trinities @ Walmart

Last time, I mentioned a well done book by evangelical philosopher Gregg Ten Elshoff on the topic of self-deception and the Christian life. He noted that one may easily have a false belief about what one believes, and he noted that there can be strong social pressures to believe that one has beliefs one doesn’t (and that one lacks beliefs one in fact has). As… Read More »You’re Foolin’ Yourself and You Don’t Believe It – Part 2

I’ve been reading I Told Me So (review) by Gregg Ten Elshof, a USC PhD who who teaches and chairs the Philosophy Department at my undergraduate alma mater. He’s been thinking about this topic for a long time (part 2) and so far, I really like the book. It is clearly written, insightful, and he trains his guns on self-deceptions by Christians in particular. Some of… Read More »You’re Foolin’ Yourself and You Don’t Believe It – Part 1

Brandon’s Siris blog has recently completed 6 years – it has surely outlived 99.9% of blogs, and is older than trinities, which is 4 this summer! Congrats, Brandon! In a recent post Brandon takes issue with my recent appeal to the principle that “if every F is a G then there cannot be fewer Gs than Fs”. Some Trinity theories are inconsistent with the (I… Read More »Linkage: Discussing Fs and Gs with Brandon (Dale)

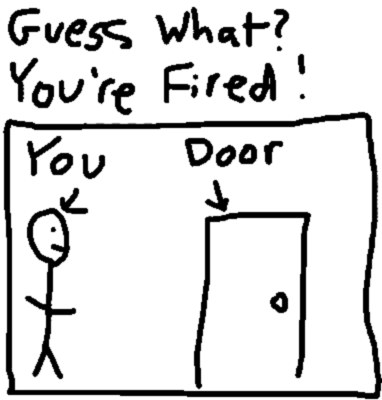

Three World Vision employees are fired because according to World Vision they don’t believe in that Jesus is “fully God” or that he’s a member of the Trinity.

Three World Vision employees are fired because according to World Vision they don’t believe in that Jesus is “fully God” or that he’s a member of the Trinity.

But inquiring minds want to know: what did they believe, what statement or statements of faith did they sign, and are the beliefs therein necessary and sufficient for being a real Christian? This time, we’re digging a little deeper.

Their website saith,

World Vision U.S. hires only those who agree and accept to its Statement of Faith and/or the Apostles’ Creed. (source)

Interesting! Note the “and/or” – employees must affirm either one or both. As we’ve noted before here at trinities, nothing in the so-called Apostles’ Creed requires belief in either the “full deity” of Christ (whatever that may mean) or any sort of trinitarian theory.Read More »No Trinity, No Job – Part 2

The latest Christianity Today magazine features an article entitle “Faith-Based Fracas”, by free-lance reporter Bobby Ross Jr. The main interest of the piece is whether or not it will remain legal for religious organizations to hire and fire on the basis of religious beliefs.

The latest Christianity Today magazine features an article entitle “Faith-Based Fracas”, by free-lance reporter Bobby Ross Jr. The main interest of the piece is whether or not it will remain legal for religious organizations to hire and fire on the basis of religious beliefs.

For the record: I support that right.

But the piece is occasioned by a current lawsuit against evangelical charity World Vision brought by three recently fired employees.

It strikes me that there are human and theological angles to this story which have yet to be told.

Here are the relevant bits from Ross’s story in CT:

Both [Sylvia Spencer and Vicki Hulse] signed statements affirming their Christian faith and devoted a decade to World Vision… But in November 2006, they and colleague Ted Youngerberg were fired. Their offense, as determined by a corporate investigation: The three did not believe that Jesus Christ is fully God and a member of the Trinity. (Bobby Ross Jr., “Faith-Based Fracas”, Christianity Today, June 2010, 17-21, p. 17, emphases added)

No doubt the reporter here was hindered by the fact that a lawsuit is underway. But the story has many obvious, yawning gaps:Read More »No Trinity, No Job – Part 1

Congratulations to both debaters on a fight well fought. (Here’s all the commentary.) Plenty of punches, thrown hard, relatively few low blows – two worthy opponents. Certainly, the fight must be decided on points, as there was no decisive knockout. Both debates are in different ways very impressive, and I learned a lot from both.

Congratulations to both debaters on a fight well fought. (Here’s all the commentary.) Plenty of punches, thrown hard, relatively few low blows – two worthy opponents. Certainly, the fight must be decided on points, as there was no decisive knockout. Both debates are in different ways very impressive, and I learned a lot from both.

Kudos to C. Michael Patton and Parchment and Pen for hosting the debate.

I hope you readers out there enjoyed my commentary on the debate. I sometimes got naggy or nerdy, and always expressed myself with typical lack of tact, but I tried to be helpful, and to show the helpfulness of philosophy and logic in thinking through these things.

In this last post in the series, a few concluding reflections on the debate.

Looking back on this debate, I see that I’ve ended up where I began: wondering what Bowman thinks the Trinity doctrine is. This, after all the debate was about whether or not the Bible teaches that.

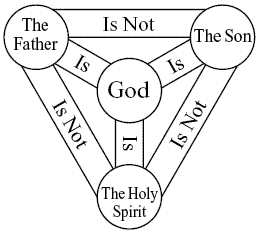

Burke argued that the Bible teaches what I call humanitarian unitarianism (he calls it “biblical unitarianism”) – roughly, that the one God of Israel is the Father, whereas the Lord Jesus is a human being and his unique Son, and the Holy Spirit is God’s power. I understand what Burke argued for, and if it is true, then nothing that can claim to be an orthodox Trinity theory is true. But I don’t, in the end, understand Bowman’s view.

I flagged this issue at the start. As the debate wore on, I settled on the interpretation that each of the Three just is (is numerically identical to) God, and yet each of the three is not identical to either of the other two. I stuck with this interpretation, all the way to the bitter end. And yet, I never did like this interpretation Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – Final Reflections

In his sixth and final installment of the debate, Bowman turns in his finest performance, making a number of interesting moves, and getting some glove on Burke. First, he tweaks his formula (here’s the previous version): The doctrine of the Trinity is biblical if and only if all of the following propositions are biblical teachings: One eternal uncreated being, the LORD God, alone created all… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 6 Part 2 – Bowman

In the 6th and closing round, Burke argues from reason, scripture, and history. From reason: The Trinity doctrine, argues Burke, is inconsistent with itself. The “Athanasian” creed presents us with three, each of whom is a Lord, and yet insists that there is only one Lord. As some philosophers have pointed out, it is self-evident that if every F is a G, then there can’t… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 6 Part 1 – BURKE

Were there any “biblical unitarians”, or what I call humanitarian unitarians in the early church?

Were there any “biblical unitarians”, or what I call humanitarian unitarians in the early church?

Buckle your seatbelts – this post isn’t a quickie.

First, to review – in this whole debate, Burke has argued that all the NT writers were humanitarians. But if this is so, one would expect there to be a bulk of humanitarian unitarians in the times immediately after the apostles. Here, as we saw last time, Bowman pounces. All the main 2nd century theologians, he urges are confused or near trinitarians. (Last time, I explained that this is a dubious play on the word “trinitarian”. My term for them is non-Arian subordinationists.) There’s not a trace, Bowman urges, of any 1st c. humanitarians – with the exception of some off-base heretical groups, like the Ebionites.

We’re talking about mainly the 100s CE here, going into the first half of the 200s. The general picture, as I see it, is this. Early in the century, we find the “apostolic fathers” basically echoing the Bible, increasingly including the NT (the NT canon was just starting to be settled on during this century). However, some of them seem to accept some kind of pre-existence for Christ (in God’s mind? or as a divine self alongside God?), and they’re often looser, more Hellenized in their use of “god” (so even though as in the NT the Father is the God of the Jews, the creator, Jesus is more frequently than in the NT called “our God” etc.) But clearly – no equally divine triad, no tripersonal God, and in most, no clear assertion of the eternality of the Son. In the second half of the century, starting with Justin Martyr, we find people expounding a kind of subordinationism obviously inspired by Philo of Alexandria, the Jewish Platonic theologian Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BURKE – Part 3

As we saw last time, Burke in round 5 argues like this: 2nd c. catholic theology was predominantly subordinationist. If the apostles had taught the Trinity, this wouldn’t have been so. Therefore, the apostles did not teach the Trinity. In a long comment (#23) Bowman objects, For some reason… anti-Trinitarians think it is bad news for the doctrine of the Trinity if second-century and third-century… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BURKE – Part 2

Burke’s fifth round opens some interesting cans of worms. First, he reiterates that the Bible doesn’t explicitly talk of any triple-personed god, but instead calls the God of the Jews the Father. His Son is Jesus, and they stand in a hierarchy as two persons – the Son “under” the Father – over the realm of angels. He says that “Scripture never includes the Holy Spirit… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BURKE – Part 1

As I explained in the previous installment, in round 5 Bowman is trying to show that not only does the Bible imply that all three Persons are divine, but also that they in some sense are the one God. In other words, he wants to show how the NT brings the three, as it were, within the being of the one God.

As I explained in the previous installment, in round 5 Bowman is trying to show that not only does the Bible imply that all three Persons are divine, but also that they in some sense are the one God. In other words, he wants to show how the NT brings the three, as it were, within the being of the one God.

To do this, he considers a dozen triadic passages, in which the Three are all mentioned together in quick succession. Last time, I mulled over his treatment of the “Great Commission” passage. This time, a few others, and I take a crack at another explanation of this triadic language.

First, as I look at Bowman’s interpretations, some of them strongly suggest that he thinks that asserting the divinity of each just is asserting each to be numerically identical to God. I looked into this more last time, but briefly, this won’t fly, as it’ll make the persons identical to one another. So it is not clear, even if his expositions are right, that really support an orthodox Trinity theory.

Second, I reiterate that Bowman does a good job here, assembling a dozen important passages, in which it is impossible to ignore the triadic language. Suppose the doctrine of the Trinity is just this vague claim: “there are three co-equal persons in God”. If that is true, that would explain why these three are often mentioned together, in a way which can suggest they are on an equal footing. I said last time that any unitarian is obligated to explain these triadic statements in a way which is both compatible with unitarianism, and which is independently motivated (in can’t be that the only appeal of the reading is that it saves one’s theology).

Here’s Bowman’s treatment of one such text:Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 3

I still mean to comment on Bowman’s 5th round, but my inner logic nerd was drawn in by some action from round 5 here, comment 19: [Burke:] “This week I hope Rob will show Biblical evidence for the essential relationship formulae of Trinitarianism: 1. Father = ‘God’, Son = ‘God’ and Holy Spirit = ‘God’ 2. ‘God’ = Father + Son + Holy Spirit .… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 2

In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

In the preceding three rounds of this debate, I have argued that the person of Jesus Christ existed as God prior to the creation of the world and that the Holy Spirit is also a divine person. If my argument up to this point has been successful, I have thoroughly refuted the Biblical Unitarian position and established two key elements of the doctrine of the Trinity. Add to these two points the premises that there is only one God who existed before creation and that the Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, and the Father is not the Holy Spirit, and the only theological position in the marketplace of ideas that is left is the doctrine of the Trinity. Since these are all premises that Biblical Unitarianism accepts, I have not defended them here. (emphases added)

I’m tired of pointing out the inconsistency of what Bowman is urging. I’m capable of hearing the many ways theorists smooth away apparent inconsistencies (making subtle distinctions), but other than a quick gesture (I think in Round 1), I hear none of these familiar notes from him. This is just to say – he’s a resolute positive mysterian. Briefly, Father, Son and Spirit are numerically three, as they qualitatively differ from one another. But also, Bowman seems to think, each of them is numerically the same as God. This is inconsistent, because the “is” of numerical sameness is transitive – if f = g, and g = s, then f = s (compare: the concept of “bigger than”). Also, it seems that he thinks Father and Son to the same god, and also, since this god just is a person (hence “who” above), they are the same person as each other. And, of course, also they are not. Sigh. Let’s stick with the vague “threefoldness” claim I started with.

Bowman ignores what I call Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 1

The “Great Trinity Debate” has been interesting, exhausting, and a bit hard to follow. It would’ve been better to have somewhat shorter posts and required post-rebuttals. As it is, some of the debate has been tucked away in the comments of the posts, while the blog plugs away on other topics. This sort of substantial, quality content shouldn’t be hidden in comments.

The “Great Trinity Debate” has been interesting, exhausting, and a bit hard to follow. It would’ve been better to have somewhat shorter posts and required post-rebuttals. As it is, some of the debate has been tucked away in the comments of the posts, while the blog plugs away on other topics. This sort of substantial, quality content shouldn’t be hidden in comments.

I previously called round 3 a draw. But my call was premature; Burke kept punching, in a long set of comments (#4-15), which substantially strengthened his case. Bowman has left them unanswered for about a week, I believe, as I post this. I re-call this round now for Burke.

Revised score up through round 4:

Bowman: 0

Burke: 3

draw: 1

What he does is address some important texts which as usually read, assert or assume the claims that Jesus created the cosmos, or just that he pre-existed his conception. I can’t summarize Burke’s long exegesis, but I’ll hit a few highlights in this post. What he shows, drawing on some recent scholarship, is that the texts in question can be given non-arbitrary, plausible readings which are consistent with humanitarian christology.

Burke also rebuts some of Bowman’s points re: prayer to Jesus. Bowman argues that Christ can’t be a creature, and must be omniscient (hence divine), if he can hear and answer prayers. This argument is hardly a knockdown one.

Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 3 Re-evaluated (DALE)