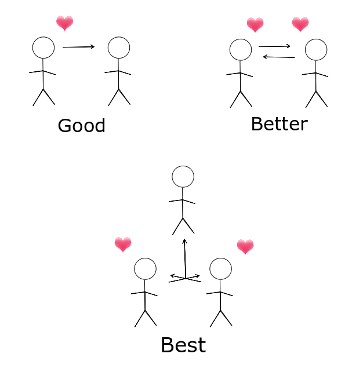

In the preceding chapters, Richard has been arguing for the impossibility of only one divine person. If there’s one, there must be more than one; more than that, there must be at least three.

In the preceding chapters, Richard has been arguing for the impossibility of only one divine person. If there’s one, there must be more than one; more than that, there must be at least three.

To do this, he’s used Anselmian perfect being theology – arguing that since God is absolutely perfect, and it would add to his perfection to have certain features, he must indeed have those. It seems that he prefers a three parallel arguments, from perfect goodness, perfect happiness, and perfect glory. (See, e.g. chapter 5.)

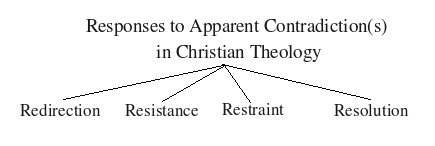

As the book goes on, though, it seems to me that he prefers the argument from happiness. Here, in chapter 21, he sums up his case, because he feels some pressure here at the end of the book to explain why all this should be considered monotheism, and not polytheism. More on that next time. Here’s what looks like his summary of his argument:

The fullness of supreme happiness requires fullness of supreme pleasure. The fullness of supreme pleasure requires fullness of supreme charity. The fullness of supreme charity demands fullness of supreme perfection. (p. 393)

This last part isn’t easy to see, but as we’ve been over it, I let it go here. In chapter 21, Richard assumes that perfect being reasoning should be applied to each member of the Trinity. If we do this, then we prove the existence of equally perfect beings, such that “all coincide in supreme equality. In all of them there will be equal wisdom, equal power, undifferentiated glory, uniform goodness, and eternal happiness…” (pp. 393-4, emphasis added)

This, he asserts, meets the requirement of the “Athanasian” creed,Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 21 (Dale)