As I said last time, Arius maintains that the Son is created from nothing (ex nihilo), but Athanasius denies this. Much of the discussion depends on what these authors mean by ‘creation’. Before we go any further then, it will be helpful to establish a working definition for ‘creating something from nothing’. This requires some care, because we’re after a definition that both Arius and Athanasius would agree to. But so long as we make the right qualifications, I think that Arius and Athanasius do agree on what it means to create something from nothing.

Just so we have a rough idea of what we’re talking about, let me begin by describing creation in the following way: something is created from nothing if it’s produced without any pre-existing ingredients. Now, that’s a very loose way of putting it, but it makes the basic idea clear enough. We know that things get produced with pre-existing ingredients all the time. Masons build walls with bricks and mortar, cavemen make charcoal with fire and wood, humans procreate with sperm and eggs, and so on. But none of that counts as a creation. Something is created from nothing only when it’s produced without any pre-existing ingredients.

But as I said, that’s a very loose way of putting it, so let me explain more carefully what I mean. In this post, I want to clarify first what I mean by an ‘ingredient’. In the next post, I will turn to what I mean by ‘pre-existing’.

First then, when I talk about some ‘ingredient’ in a product, I mean any sort of constituent which satisfies the following two conditions: first, it exists in the product; and second, it bears its own properties, i.e., it has features that other ingredients in the product do not have, and which the product itself does not have. (I choose these two conditions because they are the conditions that are needed for both Arius and Athanasius to make their theories work.)

As for the first condition, I don’t really have a good definition for what it means to be ‘in’ a product, but this first condition is meant to rule out anything the product is related to outside itself. For instance, some believe that properties are abstract entities which exist somewhere ‘out there’, and particular objects are related to those properties by exemplifying them. Such properties are not in the things that exemplify them, so they don’t count as ingredients in my sense of the word. Properties can only count as ingredients if they are actually in the product. (Thus, immanent universals count as ingredients, and tropes do too.)

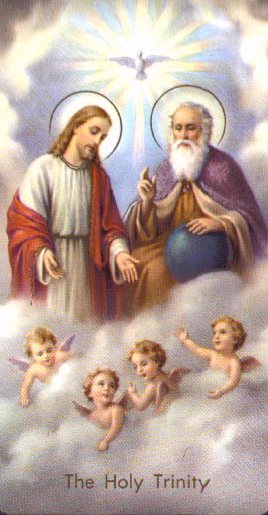

(I suppose someone could take the extreme view that a statue and the bronze it’s made from are two entirely distinct objects (sharing no parts) whose only connection is merely that they occupy the same region of space. On this view, the bronze wouldn’t count as an ingredient in the statue, for it’s not really an ingredient at all; it’s a different object altogether that just happens to be in the same spot. Besides, if we said that mere spatial co-incidence were enough to make something an ingredient, then if a ghost (or an angel, or the Holy Spirit, or a kharmic strand, or what-have-you) just happened to be floating through me at this very moment, it would turn out to be an ingredient in me, and I’m not sure I want to say that.)

The second condition is meant to rule out any ingredient that is identical to another ingredient, or which is identical to the whole product. For example, sometimes philosophers talk about ‘improper parts’ as something that’s identical to the whole. Such improper parts would not be ingredients in my sense of the word, for they are identical to the whole.

This also rules out theories where a constituent is identical in some way to what it constitutes. For instance, some hold that when a lump of bronze is shaped like a statue, the bronze just is the statue, even though it’s possible that this particular lump of bronze might not have ended up being this particular statue. On this reading, the bronze wouldn’t count as an ingredient in the statue, for the bronze just is (i.e., is identical to) the statue.

However, when I talk about ingredients that are not identical to other ingredients or to the whole product, I only mean to rule out absolute identity (i.e., the sort of identity where x and y are just the very same thing with all the very same properties). But I wish to allow weaker kinds of identity or sameness.

For instance, some (e.g., Brower and Rea, Lynne Rudder Baker) entertain a kind of sameness where two things can be numerically the same, but not identical. For example, a statue and the bronze it’s made from are numerically the same object, but they are not identical, so the bronze would count as an ingredient in the statue in my sense of the word.

These sorts of lesser identity or sameness are allowed here. All that’s ruled out are ingredients that are completely and absolutely identical to another ingredient or the whole product.

(Note that this blocks problems for the Trinity that arise from the transitivity of identity. If some ingredient were absolutely identical to the Father, and if that same ingredient were also absolutely identical to the Son, then by the transitivity of identity, the Father and Son would be identical to each other. Neither Arius nor Athanasius would allow that.)

This allows a fairly wide range of entities to count as ingredients. Of course, a physical part, or any sort of proper part, counts as an ingredient. For example, the two sides of a pan each count as ingredients in the pan. They are not identical to each other or to the whole pan, and they each have their own features (as is clear when one side of the pan is hot and the other side is cool).

Constituents like Aristotle’s matter and form also count as ingredients in whatever they jointly compose. The lump of flesh and the soul that make up Socrates each count as ingredients in Socrates, for they are in Socrates, but they are not identical to each other or to the whole body-soul composite.

So something is created from nothing if it’s produced without pre-existing ‘ingredients’, where ‘ingredients’ has the sense that I’ve just explained. In the next post, I will explain what I mean by ‘pre-existing’.

I have tried to find any mention of the word trinity in the bible and its not there.I have to say that,its a christian doctrine and not a biblical teaching.My personal opinion is that,been Christ means been possessed by the spirit of the Almighty in such a manner that the individual has no control of his/her actions.This is quite different from been inspired which I understand to mean external spiritual interaction of an individual with the Creator’s spirit.We have to admit that Jesus was born and was flesh and blood human,which leads me to the conclusion that prior to his birth no one has prove of his existence.

I had in mind a ‘homoiousian’ position that gets cashed out in terms of three numerically distinct instances of the same kind (deity). I should have waited for your upcoming post on a ‘_pre-existing_ ingredient’– b/c my question has to do with this condition in particular. So I’ll wait until then to ask my question – b/c you may already have answered it.

PS. The post-Arians I can think of, off the top of my head, maintain that the Father’s unbegotteness is part of his essence, and so it’s impossible to produce a ‘similar’ essence. But maybe you’re thinking of some other camp/theologian?

I’m not sure, but I think you’re talking about the view that the Father and Son are the same in kind, but distinct in number, sharing no parts or constituents. Is that right?

Two things.

First, which semi-Arian camp are you thinking of here (there are lots of them)?

Second, I don’t know what your question is. Are you asking what I think about it? If so, I don’t really have an opinion on it.

I’d be interested, after you finished the discussion of Arius, how you figure semi-Arrians in this. Suppose a semi-Arrian agrees (with Arius) that there is no pre-existing ingredient that is in the Son, but suppose there is a pre-existing ingredient x that is maximally similar to a produced ingredient y. Whereas Arius takes a strong stand on the subordination of the Son to the Father, these semi-Arrians would say that the Son is only subordinate to the Father in the sense that the Son causally depends on the Father (much like Origen says). Nevertheless, the Son’s essence is maximally similar to the Father’s essence; on this basis the Son is equal in perfection to the Father except for the property of being causally dependent on the Father.

Just a thought:

I think your criteria for something being created ex nihilo may be a bit too strict. For instance, image that there is an eternally existing, increate handle. Suppose further that other than God, this is the only thing that exists. Now suppose that God were to create ex nihilo a few other things such that these things plus the handle brings into existence a guitar case. Did not God create the guitar case ex nihilo? It seems to me that he did.

Perhaps you could respond by saying that the handle is not an _essential_ ingredient of the guitar case. That is, the guitar case could still exist without the handle. But, in doing so, I think, you would still have to amend your definition and in it address the distinction b/t essential and accidental ingredients.

Comments are closed.