In discussing the Trinity or Incarnation, I often have an exchange which goes like this:

In discussing the Trinity or Incarnation, I often have an exchange which goes like this:

- someone: Jesus is God.

- me: You mean, Jesus is God himself?

- someone: Yeah.

- me: Don’t you think something is true of Jesus, that isn’t true of God, and vice-versa?

- someone: Yes. e.g. God sent his Son. Jesus didn’t. God is a Trinity. Jesus is not a Trinity.

- me: Right. Then in your view, Jesus is not God.

- someone: But he is.

- me: So, you think he is, and he ain’t?!

- someone: [silent puzzlement]

In this post, I want to explain the part in italics. First: a point of clarification. The second and third lines are important. When many say “Jesus is God” they just mean that in some sense or other Jesus is “divine.” (This could mean a lot of things, depending on one’s assumed metaphysics.) But this sort of person (line 3) understands Jesus to be “divine” in the sense of just being one and the same as God – that Jesus is God himself – one person, so just one (period).

In the italicized line, I’m applying something called Leibniz’s Law, or the Indiscernibility of Identicals. I sometimes put this roughly as, some x and some y can be numerically identical only if whatever is true of one is true of the other. That’s a sloppy way to put it.

In logic, a more precise way of stating it (used e.g. by Richard Cartwright) is:

(x)(y)(z) ( x= y only if (z is a property of x if and only if z is a property of y))

Literally: for any three things whatever, the first is identical to the second only if the third is a property of the first just in case the third is a property of the second.

The basic intuition is that things are as they are, and not some other way. So if x just is (is numerically the same as) y, then it can’t be that x and y qualitatively differ. This seems undeniable.

There are a few problems, though, with the above formula, which any person trained in philosophy may spot.

First, don’t things change? e.g. Last year you weighed 200, and now you weight 210 lbs. But does this mean that the you of 2010 is not numerically the same as the you of 2011? Ridiculous! Things can qualitatively change while remaining numerically the same. That’s just common sense.

Second, what about this property: being believed by Laverne to be innocent. Suppose that Casey Anthony’s lawyer mounted this defense:

Ladies and Gentlemen of the jury. I submit that we can be sure that Caylee’s killer is not one and the same as my client Ms. Anthony, for the killer has a feature she does not: being believed by Ms. Laverne Shirley of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to be guilty of murder. I’ve got Ms. Shirley right here, so you can just ask her.

This would move the defendant to tears, as it is such an obviously stupid defense.

Strictly, then, there are two sorts of counterexamples to the principle I stated above.

I haven’t concerned myself much with this so far in print or online. I’m more concerned with the fundamental intuition (that is, the evidence) imprecisely gestured at above, than I am with coming up with a counter-example-proof universal principle. When arguing about God and Jesus, I just stick with differences which are at a time (or eternal) and which are intrinsic, or which are relational, but don’t have to do with intentional attitudes of third-parties, like beliefs. (I take mental states or actions or stances to be intrinsic to the self whose they are.)

Thus, one of my favorite examples has been that one night in the Garden of Gethsemane: at that time, Jesus didn’t want Jesus to be crucified (he was asking that this may be averted, if God would so permit) yet God did want Jesus to be crucified (that was his plan all along). Or again: if you think God is triune – that would be intrinsic to God and eternal – either something which holds at all times, or in timeless eternity. If one thing is always triune and the other ain’t – we’re not talking about one thing here.

But here’s a crack at a principle which is necessary, exceptionless, and self-evident: sadly, it requires 4 variables. It requires in addition just one 3-place predicate W (a, b, c). This is to be read: a is a way b is at c, or a is a mode of b at c, or a is how b intrinsically is at c. Here then, is my preferred version of Leibniz’s Law:

(w)(x)(y)(z) ( x = y -> (W(z, x, w) <-> W(z, y, w)))

Literally: for any four things, the second and third are identical only if the fourth is a way the second is at the first just in case the fourth is a way the third is at the first.

Dang, that’s ugly. Perhaps better to use the variables:

For any w, x , y, and z: x just is y only if: z is a way x is at w if and only if z is a way y is at w.

This gets around the two sorts of problems noted. This principle would not let us infer that I’m not numerically the same as my slimmer, younger self. Nor would it license a foolish juror to exonerate Anthony on the grounds that the killer, but not she, has the feature being thought by Laverne to be guilty, for that phrase does not pick out any intrinsic way Casey Anthony ever has been, is, or will be.

The predicate W (_,_,_) can be interpreted in different ways. Not believing in properties, but believing in primitive modes of things, I like to understand it as above. But if you like, interpret W in terms of property-instantiations (if you believe in universal properties) or individual properties (tropes) if you believe in those. It is just meant to refer to things we’re all familiar with, like my being happy now, that ball’s present redness, etc.

It seems to me that this formula captures the intuition gestured at above, and that it is self-evident – something a normal, adult human knows to be true upon coming to understand what it means.

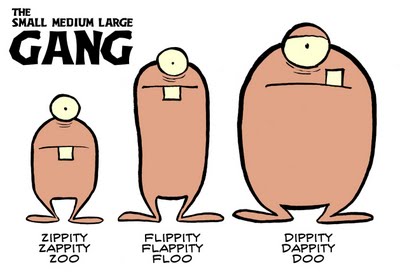

Dear reader: you understand it, with a bit of effort, no? And so, does it not have that obvious shine of truth to it that this has:

For any x, y, and z: if x is bigger than y, and y is bigger than z, then x is bigger than z.

You know this to be true not just of the cartoon here, but of any three things there are or could be, right?

And so, if you’re very sure this version of Leibniz’s Law is true, you should be as sure that Jesus and God are two, as you are that they have ever, do, will, or just could differ (be different ways). You too are now a dastardly “denier of the divinity of Christ,” but only in the sense described at the top of this post. Whether Christ is divine in some other sense, e.g. possessing the divine nature, or being the member of a perfect society, is another question.

Back to the conversation above, last two lines. You think them to have differed. Yet, things which have differed can’t be numerically one. Ergo, in a sense, you already believe them to differ. Or at least, you’re already in a sense committed to their non-identity. If you don’t believe this outright, you should, once it is pointed out that it follows by a self-evident truth from things you do believe. You then have a choice – revise those old beliefs, so they no longer imply this new one, or accept this new belief, and adjust other beliefs according. I suggest that your beliefs about = and Leibniz’s Law are not good candidates for revision, though.

Interestingly, I never have these sorts of conversations with people who understand what identity is and believe there are truths about it – i.e. philosophers, philosophy majors, theologians who have studied a bit of philosophy and logic. They simply accept that Jesus and God aren’t one and the same (aren’t identical), and go on to theorize accordingly.

Dear philosophical readers: can you provide a counterexample to my version of Leibniz’s Law?

Pingback: Orthodox modalism (Dale) » trinities

Dale

Your entire post is a consequence of the (tacit) assumption that the word God (necessarily) refers to a an individual entity/being.

Do you want a counterexample? Here it is, and it doesn’t even need to involve Leibniz’ “indiscernibles”.

Just replace, in your original exchange: Jesus => Paul; God => man; send => sire; Trinity => paradox

someone: Paul is man.

me: You mean, Paul is man himself?

someone: Yeah.

me: Don’t you think something is true of Paul, that isn’t true of man [in general], and vice-versa?

someone: Yes. e.g. man, [in general] sires children. Paul didn’t. Man is a paradox. Paul is not a paradox.

me: Right. Then in your view, Paul is not man.

someone: But he is.

me: So, you think he is, and he ain’t?!

someone: [silent puzzlement]

Pingback: trinities - On an alleged counterexample to Leibniz’s Law – Part 2 (Dale)

Yes, I think souls can and do change in all those ways. But I don’t think this entails their having parts.

Well, I should have said, “Dale, do you agree or disagree with the last three sentences?” 🙂

Thank you, Dale. We disagree about various details of physics and substance dualism such as your conjecture of non-physical spatial dimensions, but we might agree on some basics about the continuity of identity over time. If I may, I want to make sure that I understand your model while I make an informal analysis:

You propose that humans have a non-physical but spatial soul that is subject to time’s arrow. These souls have intrinsic properties while I suppose that the souls also have non-physical parts. For example, the souls can change in regards to (1) their amount of knowledge, (2) their emotional development, (3) their moral development, and (4) their location in the observable universe. Dale, do you agree or disagree with the last two sentences?

Hi James – I suppose that souls are non-physical, yes, but temporal and spatial. It’s just that they don’t “take up” space like physical objects do. But it some sense they have location. About other dimensions, I know this is uncool, but I guess I only believe in three.

Pingback: trinities - On an alleged counterexample to Leibniz’s Law – Part 1 (Dale)

I have what I hope is a clearer question: Do you conjecture that the human soul is nothing but non-physical mental substance or do you conjecture that the human soul also has hyperdimensional parts?

Thank you, Dale. Sorry that I am not fluent in philosophy terms. I hope for more clarification, if I may. Do you conjecture that a human soul is literally non-physical or do you mean something along the lines that human souls are non-spatial in regards to the observed space dimensions but human souls have some type of hyperdimensional physics? Also, do you understand my question at all? 🙂

Brandon – I’m trying to parse your argument about “intensional distinctions.” I think I’ll attempt that in a post. Hope you can weigh in there.

Your claim that a definition is required to admit something as self-evident is, I think, wrongheaded. Here’s something which is self-evident (also, necessary, universal): If something is in pain at a time, then it is conscious at that time. I’ve not defined what it is to be in pain (who could?) nor have I defined what it is to be conscious (again, who can?) nor again “time”, but this truth is self-evident. There aren’t even any obvious nominal or operational definitions at hand either, at least that I can see.

Brandon – thanks for your reply. I’ll break mine into shorter parts.

Reading your first paragraph, one would think that the notion of a particular, intrinsic property is a very difficult one. But it is not. Everyone understands talk of this apple’s redness, or of this man’s intelligence, or that planet’s mass. Metaphysicians understand these in different ways, of course – and that they do so show that they all understand what is being referred to. I think it is kicking up a cloud of dust to point out the different uses of terms like “property.” I’m thinking you just don’t have a metaphysics of these things, or at least you don’t want to own up to one in the context of a theological discussion.

You sort of suggest that you just want to hold the old view that a property just is a predicable, something (reasonably) sayable of an object. If so, I’d protest that I have no idea what this means, for such a thing might be a word, a concept, a universal, or something else. And again, “reasonable.” 🙂

James, those are not what philosophers call properties, but rather parts or perhaps components. I property is like Bob’s being 2 meters tall, or his having an IQ of 120.

If I understand the question, I’m what philosophers call a substance dualist. I think a human self just is a certain non-physical entity, a soul. This self of course uses and in various senses depends on a body. But I’m inclined to think of a body as just a big, complex, orderly event.

I’m asking: what sort of particular properties do you believe in?

My answer would be that this is an obviously ill-formed question as it stands. What counts as a property depends on the context. Sometimes one will want to distinguish between properties and accidents, sometimes between properties and subjects; sometimes the terms will be isomorphic to predicates (properties just are what predicates refer to), sometimes will include modalities and sometimes won’t, etc. So the question can’t be made sense of without specification to a context. You can ask, in other words, what kinds of properties I think really exist if we use ‘properties’ to indicate propria, or if we use it to indicate non-essential qualities, or if we use it in a sense in which parts of the definition of the essence are the properties of the thing, or if we use it in a sense in which properties are what identifies the possible world, etc.; but asking what kinds of properties I think exists makes the same error as asking what kinds of intuitions I think people can have, namely, the error of thinking that I would use such a historically malleable term in a single univocal sense. In the broadest sense, properties are just whatever we can reasonably attribute to something as belonging to it; what we can reasonably attribute to things will depend on what we are doing, because reasonable attribution is not invariant across contexts. For some things being to the right of something will be something reasonably attributable to it as belonging to it somehow, and thus could be called a property of it; for some things it won’t. If I were proposing as self-evident a principle that involved properties, I would have to define what I meant by ‘property’ relative to a context; there would be no way for anyone to know what I meant without it. But I’m not, and there are too many to make it reasonable for me to go around playing blindman’s bluff trying to figure out what you have in mind, particularly since, to know that the principle is even a candidate for being universal, necessary, and self-evident, you must already know what it means, and, assuming it’s not an ineffable truth, should be able to convey it.

I don’t really care how abstract or concrete the discussion is; but I do want definitions. Definitions and definitions alone are the test of whether a claim genuinely fits the bill of a “universal, necessary, and self-evident”. They don’t need to be rigorous accounts of the natures of things (nominal or operational definitions would be fine), but I do need to know how you are using the words, or I don’t know the limits, conditions, or boundaries of the terms, and thus don’t actually know what the principle is.

So, God-as-subject just is God-as-object. I assume you’re assuming that, because the counterexample must make the antecedent true and consequent false. But you think they can differ? What would be a mode of one which is not a mode of the other?

That God as subject is subject and God as object is object. After all, it’s at least enough to distinguish them that we can put God, under the intension of ‘subject’, into x, and God, under the intension of ‘object, into y, and keep the two distinct all the way through. If this kind of intensional distinction is or can be a distinction in intrinsic modes of subjects as opposed to those of objects, then the consequent equivalence is broken without breaking the antecedent identity. If extensionally identical values of variables can under any circumstances have intensionally distinct intrinsic modes, the conditional doesn’t hold for those.

All identity statements have to assume that some intensional distinctions don’t matter. In x=y, we obviously are intensionally treating x and y differently in some sense — they get different letters to indicate that they are different variables and they have different locations in the equation (to the left and the right of the equality sign, for instance). We simply assume that these can be ignored to make sense of the statement as an identity statement; this allows us to focus on purely extensional matters. It’s when we get into the sorts of intensions that are typically handled by things like modal operators that things get tricky. It’s precisely this that causes problems for the standard version of the Indiscernibility of Identicals — it fails in certain kinds of plausible temporal logics, epistemic logics, etc. (because it fails to take the quirks of the relevant intensions into account), which is equivalent to saying that you can propose temporal, epistemic, etc. scenarios that are plausible counterexamples.

In essence, the issue here is that, assuming that the principle is true and that this is not a counterexample, we seem to face a choice among the following:

(1) We can deny that, in a being that necessarily knows itself and thus is necessarily both an object and a subject of its knowing, being an object or a subject is not an intrinsic mode. In effect, this means that, whatever intrinsic modes, the fact that a property, feature, or quality is necessary to a thing is not on its own a sufficient reason for thinking it is an intrinsic mode.

(2) We can deny that there is any such thing as self-knowledge in a strict sense: subjects and objects of knowledge are always non-identical. In effect, we are saying that being a subject and being an object is a difference in intrinsic modes and therefore rules out identity between subject and object. Knower and known are always different, although, of course, they could be related somehow.

(3) We can hold that being a subject and being an object are both intrinsic modes, but that in self-knowledge they are not different intrinsic modes. This is equivalent to saying that self-knowledge does not require a distinction between subject and object; you can have self-knowledge without a subject or object in the distinguishable senses that we usually think of actions having subjects and objects.

Possibly there are others; if so the list can be extended. But since each of these gives us a very different conception of what an intrinsic mode is, then, since the point was that the modified LL has to be self-evident, (assuming it actually is self-evident) at least one of these must be self-evident for the sense of intrinsic mode that is relevant here (or the necessary self-knowledge case is a counterexample). Keep in mind that I’m not here proposing a counterexample: I don’t know what you mean by intrinsic modes so as to be able to say whether it’s a counterexample or not. I am instead trying to figure out what you mean by intrinsic modes from the behavior of the principle in unusual situations. You can take your pick of any of the choices, or add any others, and that’s fine; this is not an attempt at refutation, but an attempt at figuring out what you mean by intrinsic modes by looking at what about your conception of intrinsic modes would rule this out as a refutation.

On the possible worlds case, I take it that it would follow that what something could be or have is never an intrinsic mode of it in the sense relevant to the principle here. (I don’t really care what other people might do, but only what you are doing; for one thing the others are not the ones actually proposing the principle, and for another, as far as I know they might very well do very different things; if we get into hypotheticals we will never have an end, because we can take any non-self-contradictory principle about intrinsic modes and propose hypothetical answers for what somebody could assume, ad hoc, that intrinsic modes are in order to keep the principle from having counterexamples. What matters is whether, maintaining the same meaning of the same terms, the principle in fact does have counterexamples. If it doesn’t, one can see how far that applies to analogous examples in alternative metaphysics. But if we let the meaning of the terms jump around from the beginning, we aren’t finding principles that are irrefutable because they are self-evident but principles that are irrefutable because they are understood equivocally.) In other words, we are to assume, for seeing how you understand this principle, that only what is actually the case is even a candidate for being an intrinsic mode?

I notice that the nonrelational sense of ‘intrinsic property’ came up above; obviously this is relevant to the self-knowledge case. In the sense you are using the term, do you think that all intrinsic modes are nonrelational, or are there at least some relational intrinsic modes (e.g., necessary ones)?

Sorry about this piecemeal. I need to clarify that when I say that in God’s perspective there are no intrinsic properties in creation, then I mean that nothing in creation has a necessary existence. However, from God’s perspective, every creature has its intrinsic identifying essence, which is more along the lines of our topic. 🙂

So, how do you define and identify a creature’s intrinsic identifying essence?

I suppose that anybody believing in soul sleep would reject the existence of a hyperdimensional spirit, so that would be a different model.

Likewise, I am excluding possessions apart from the body and spirit in this concept of identity over time.

Dale, I was thinking of that a person’s properties consist of their biological body and hyperdimensional spirit. I suppose I am unsure how to identify the intrinsic properties of a person going from fetus to childhood to adulthood to postmortem. How do you identity a person’s intrinsic properties? Also, there are no intrinsic properties in creation from God’s perspective.

James, if by properties we mean intrinsic ones (vs. relational ones) then trivially, if things differ in properties, then they intrinsically differ. Are you thinking of “properties” in the sense of “possessions”?

No, I don’t think it is a counterexample. If you’re willing to go this far, you’re simply accepting that contradictions can be true – e.g. that a certain sentence is and is not true. This is what philosophers call “dialetheism.” This has always been unpopular, at least among “western” philosophers.

Philosophers vary a lot in their response to the liar’s paradox; I prefer the view that it is neither true nor false.

This is a good question. Some think that what I’m calling self-evidence requires that all agree, or that all experts agree. It does not. It is a sad fact that for just about any claim about important things, you can find someone who disagrees. e.g. that any self exists, or that more than one self exists, or that there is any material thing whatever, or that there’s more than one entity in reality, or that the cosmos exists, or that all contradictions are false. The fact is that for the sake of a treasured theory, one may deny just about anything. Still, this fact that one is denying may be something that apart from social influence and other irrational factors, is because of how we’re built, obvious to all normal adults. It’s just that we humans really can and do deny the obvious. (Of course, what we deny, and what we really disbelieve can be very different!)

Can’t go into it now, but what I’m calling self-evident is what Plantinga calls “properly basic” beliefs, and pretty much what Thomas Reid calls “first principles.” I think this is a very important concept in epistemology, and it is to our intellectual peril that we don’t learn from these all-time giants of Christian philosophy.

Dale said,

Dale, I never said anything about intrinsic differences between DT1 and DT2. I merely said that they had some different properties. I do not understand the relevance of your comment that I quoted. Could you please explain what you said?

Hi Katie,

Welcome! Briefly, you’re espousing what metaphysicians call the doctrine of temporal parts. It identifies you not with any one thing at a time, but rather with the whole, as it were, space-time worm. It conceives of objects, and selves, as spread out across time, rather than lasting whole throughout it. I reject temporal parts, for many reasons. One is that I think it basically says that intrinsic change is illusory. What looks like on thing changing will in fact, on their doctrine, be a series of similar things. But you’re right that this would remove any problem about L’s Law and change – each unchanging Katie-stage would not be = to any other, and yet Katie (the whole series) would be = to herself. Each stage would “be” her (i.e. a temporal part of her) but would not be = to her. Have to run – thanks for weighing in!

Brandon, I’ve taken your concerns seriously, answered your queries, and tried to understand where you’re coming from.

I’m trying to have a conversation with you, which requires that you too answer questions. I’m not weaseling. I’m asking: what sort of particular properties do you believe in? Then, we can talk about whether my principle, understood as you would like, is something to which is obviously true to you. I’ve said I’m not sure I can give a proper definition of a mode, but I stand by the claim that we all believe in something like particular properties, and I claim that we all have this intuition. It seems to me you want to keep things on an abstract level.

Qualify it how? Please state the revision you have in mind.

Which variable do you think is useless?

Come on. I’m just making the above request. You know I respect you and your opinions.

No, I haven’t considered this – thank you.

Yes, I would say that its awareness of itself is a mode of it.

I’m not sure how to take this qua-talk:

Let’s just call it God. So, God-as-subject just is God-as-object. I assume you’re assuming that, because the counterexample must make the antecedent true and consequent false. But you think they can differ? What would be a mode of one which is not a mode of the other? Please say a bit more.

So Dale in w1 is mad at t1, but Dale at w2 is not mad at t2. And yet, Dale in w1 = Dale in w2. The objection, then, is that we have identical things which differ at a single time.

This objection doesn’t worry me too much. I think that the actual world Dale is the only real Dale here, if I could put it that way, the only self-identical thing. To talk about me being = some “Dale in another world” is really just a way of supposing what’d be the case if things were somewhat different than they are. We talk as if there were “another Dale” just to talk about the truth that I could have not been mad at a certain time. In short, I believe in objective modality, but not in the reality of merely possible worlds.

Other people, who have Plantinga-type views about possible worlds, would get around this, I think, by indexing properties to worlds. So the Dale in the actual world would have the property mad-in-w1, and the other Dale would have the property happy-in-w2 or not-mad-in-w2 or whatever. But this other Dale would also have mad-in-w1, and the actual Dale would have not-mad-in-w2 as well. So, it’d not be a counterexample, on that view of possible worlds.

Hi Dale,

I’ve enjoyed reading this blog for a while, but this is my first post. 🙂

I’m still learning formal logic, so I want to make sure I follow. You’re just saying that x = y only if x and y are the same way at the same time, right?

If so, I agree that this is perfectly self-evident. However, I think adding the extra variable for time is only necessary if our concept of a “thing” is too vague. We live in dimensions of space and time, and as such what constitues any thing (say, me) ought to be considered to include both my extent in space and my extent in time. It makes no sense, then, to speak of a different “me” today and yesterday; at both times you merely get a snapshot from my whole temporal existence (much like examining one of my cells under a microscope is one snapshot of my physical existence). With this understanding it seems you can use Leibniz’s Law without any trouble arising from the apparent “change of an object over time”–the object is actually (to put it poorly) the sum of its states through time. Any “property” of that object may then be its state at a given time, its state over an interval of time, etc. So I don’t really disagree with you, but I think confusion over identity can be clarified without complicating the formula.

Hi Dale,

I’m wondering if the Liar’s Paradox might present a counterexample to the law. Here you have exactly one proposition/sentence/utterance/ that both has the property (or is in the mode) of being true and not true at the same time.

Also, might not the fact that there is disagreement among logicians about whether the Liar’s Paradox can be solved weaken your claim that the law is self-evident?

What do you think?

Thanks,

Greg

Why the hostility? My principle is much like, e.g. Cartwright’s. Why think it strange that someone tries to refine a formula to get around counterexamples, rather than hand-waving about “contexts” on necessary restrictions? And why think it strange that I want to make a point in my preferred lingo, while being as neutral as possible about property-theories?

But this is not what you’ve been doing. You’ve been deliberately refusing to clarify your “preferred lingo” in a discussion where the precise question at issue is whether the principle in question is so universal, necessary, and self-evident any adult could see that it is on knowing the meaning of the terms. Having made that strong claim, you seem to be deliberately dancing, and indeed doing some surprisingly high-handed dancing that refuses to take any concerns seriously, in order to avoid having to do what would be required to back that up: namely, letting us know what the actual meanings of the terms are.

There are so many things about what you are doing here that I simply don’t understand at present. To take just one example, if you’re going to pack everything into predicate W, there’s no need to go up to three variables. Simply take the original LL and qualify the predicate in the consequent so that it, too, deals with intrinsic modes under a quasi-temporal condition. All problems solved, and it is clear what is going on, even though we would still need a precise definition of intrinsic modes: the scope of the law is being restricted to those domains where the modal problems don’t arise. So why the juggling with the variables? The variables themselves don’t change the fundamental problem, which as I noted in my first argument (which still stands as far as it goes), remains for any expression analogous to LL except for number of variables. And your response confirms this: all the weight actually falls under W, which you keep gesturing at vaguely. But, again we could have a predicate analogous to W at the simpler LL stage. So why the extra layer of complexity? I don’t know. If I knew how intrinsic modes were supposed to be working here, conceivably it might make sense, but I don’t. But, apparently, no matter how much I tell you that I don’t, you’re just going to assume that I really do and am lying, and just tell me to use whatever terms I usually use to talk about what you’re talking about. Let’s not operate on the assumption I really already know what you’re talking about, so far as even to have a preferred terminology for it, but am just being stubbornly obtuse, and let’s just go, for the sake of the argument, with the idea that I really do need actual explanations.

On your explanations here about intensions of intentionality, we’re still at the level of examples, and therefore guessing at what could be a counterexample on the basis of vague analogies, but here’s a question that may help: if there is any entity that necessarily knows itself completely, its being both a subject of self-knowledge and an object of self-knowledge would seem like an intrinsic property. Now, if its complete self-knowledge is genuine, itself as known by itself just is itself as knowing itself. But itself as object can’t have all intrinsic modes in common with itself as subject, because the intrinsic properties of objecthood and subjecthood themselves are different: objecthood and subjecthood are intensionally different and this is essential to what they are. Thus it would seem that itself as subject and itself as object are intensionally different, that this intensional difference is intrinsic. So it seems at first glance that we have itself as subject just being itself as object, and yet itself as subject being distinct as to intrinsic modes from itself as object. I assume you’ve considered cases like this, so the question is, why isn’t this a counterexample?

Or take another alternative. Assume counterpart theories of modality are false, and that your counterparts in possible worlds are, in fact, just you. This is at least a common way of thinking. But we can still talk about what you would do in other possible worlds. And this means that the you in possible world w1 has features that the you in possible world w0 don’t, and vice versa. But the you in possible world w1 has all its features intrinsically — that’s what locates it in w1, and so also with the you in possible world w0, or in any other. But this would generate counterexamples to your principle. So your general criteria for what counts as an intrinsic mode or property must rule this kind of reasoning out as self-evidently false (for those criteria). How?

Then your agreement in Post 28 that DT1 and DT2 have some different properties indicates that your formulation or perhaps any formulation of Leibniz’s Law fails to explain the continuity of identity over time. Do you agree or disagree?

No – x=y means that x and y are numerically one – they just are the same entity. So, at any given time, they can’t differ it how they intrinsically are.

The point of L’s Law is that if you discover some such difference between some x and some y, they are two, not one and the same.

Dale, If I correctly understand this discussion of your model, then x is identical to y when x has some same properties as y and also x has some different properties from y. I conclude this because you agree that DT1 and DT2 have some different properties. Do you agree?

DTL is a split second or perhaps 10^35 Plank units older than DTR.

Why the hostility? My principle is much like, e.g. Cartwright’s. Why think it strange that someone tries to refine a formula to get around counterexamples, rather than hand-waving about “contexts” on necessary restrictions? And why think it strange that I want to make a point in my preferred lingo, while being as neutral as possible about property-theories?

Yes, that’s how I’m using it. Yes, people use “mode” in different ways. All you have to do is ask for clarification. I’m not familiar with the whole history of the usage of “mode” so I appreciate your points there.

It’s not clear that I owe a proper definition here; I don’t think Socrates was so clear about the point that some of our basic concepts are not going to be definable. I think everyone has the idea of a way a thing is; normally, we philosophers are taught that these are just properties, but I think property-theory raises as many problems at is solves. Still, my modes are much like properties (or if you like, one-place relations), thought of as particulars. It is interesting that all metaphysicians have something like this. If you think of properties as universals, you may also acknowledge particular ones. Or if not, you have events or states or facts which are particular – e.g. this thing’s instantiating the universal redness. If you’re a nominalist, you have brute similarities, and need a term to talk about these. If you’re a trope theorist, you have particular properties. Why not call any of these “modes”? Those are most of the bases, of the top of my head.

So rather than complaining about all the things “mode” might mean, I think you should understand my principle as you prefer, and then agree or disagree. If you agree, then see if it follows, on your way of understanding it, that the Father is not the Son.

Intentional states, I do assume to be modes of the thinker, aka intrinsic properties. They are unique ones, having a vector-like way of pointing to things (which may or may not be there) outside them. e.g. your believing that my formula is obscure

So, e.g. the ability to survive being smashed flat, or to be possibly spherical (had by a mass of clay). I think those should be modes, they’re not immediately observable, but do seem to be ways the mass is now – it has those potentialities.

I think I’ve met the burden, have I not? What others call mental states, events, or properties are modes of the thinker. What others call modal properties are modes of the thing.

It’s not so much like a referee throwing a flag, as it is like a judge doing some more questioning before deciding the case. Fair enough. Let me know what you think, Wapner. 😉

I need to be clearer about DTR. DTR is not the reflection but the person being reflected in the mirror, which is a split second before the person looking into the mirror. We could also call DTR DT1 and DTL DT2 while DT1 is a mere split second before DT2 instead of the first scenario with DT1 being years several years before DT2.

Yes.

Yes.

? The image of me is similar to me, but it is not numerically the same as me. But yes, one embodied human is both reflected in the mirror and looking at it.

I don’t follow you. If DTL just is DTR, why would anyone think they have those differences?

Hi Smeagol,

You’re trying to give a non-question-begging refutation of my principle. It’s a bit unclear how to take this. But if it means that one and the same self both had a lacked a feature, being-Master’s-friend at one time, it’s assuming the very thing that needs arguing for. So, it begs the question. In my answer above, I’m just saying that seems impossible.

I think we understand what Tolkien is doing, though. Your (2) should be understood as the claim that one self had desires (to be loyal to Master, and to steal “the precious”) he couldn’t both fulfill. So he “wasn’t Master’s friend” meaning that he wanted to steal his treasure. And yet he “was the Master’s friend,” meaning that he wanted to be loyal, to serve the Master’s interests.

What do you think?

Anyway, continuity of identity over time is not the relative identity concept relevant to the Trinity.

Dale, I have some clearer ideas on this:

We agree that DT1 and DT2 are identical to each other. But do we also agree that DT1 and DT2 have some different properties due to years of biological changes such as your example of weight difference?

Also, at the micro level, we agree that DT reflected in the mirror (DTR) is identical to DT looking in the mirror (DTL). But do we also agree that DTL and DTR have some different properties at the quantum level and micro different respiration properties?

Yes, I was irritated at your response, for which I apologize. But you had promised something analogous to Leibniz’s Law that would have the obvious shine of truth and instead gave something totally unlike what anyone actually thinks of as the indiscernibility of identicals, based on some metaphysics of internal modes under quasi-temporal conditions all balled up in a workhorse predicate, W, which you’ve not yet given a clear definition. If you’re going to claim something is so lucid as to be self-evident while hiding information essential to understanding it, you’re going to irritate people. Had it been intentional, that’s what we would call around here the Old Bait-and-Switch.

No clue? Brandon, that sounds a bit overblown.

I stick firmly by my phrase; I am not exaggerating how confusing your discussion of intrinsic properties has been so far. In general, what counts as intrinsic varies according to what one is doing. If you are speaking in terms of broadly Leibnizian metaphysics in which all properties of a thing are intrinsic, what can be counted as intrinsic is a massively larger group than if you have a theory in which nothing is considered intrinsic unless it is essential and necessary. I would guess from what you’ve said that you are ruling out both of those as self-evidently wrong, since those would give your principle some odd ramifications, but you’ve only given vague indications about where between the two the acceptable range of positions lies. Whether or not ‘being happy’ (to use an example from your post) is intrinsic depends on such things as whether the intrinsicness of a property is required to exhibit a substantial or quasi-substantial character (stand-alone); or, to put it more broadly, a crucial question is whether there are any intrinsic relational properties — some people use ‘intrinsic’ in ways that would include some relational properties, others take ‘intrinsic’ to be synonymous with ‘non-relational’. ‘Intrinsic mode’ has a particular meaning in certain branches of scholastic philosophy; it means a purely supervenient property that nonetheless follows in some way from the essence or nature of a thing; thus there are things more intrinsic than intrinsic modes, and there are intrinsic modes that are extrinsic to other things. And so on, and so forth. It really does need clarification if you’re going to use it to reject counterexamples.

(Likewise, to answer your question about ‘modes’, since ‘mode’ doesn’t have a univocal meaning in every domain, what I will call a ‘mode’ will vary from domain to domain. A Malebranchean mode is just not the same as a Scotist mode, etc.)

I still don’t have a clear notion what you mean by ‘intrinsic’ in this context. I feel like Socrates must have felt when, upon his asking for a definition, people just gave him lists of examples. What you just told me is that if I want to know what an intrinsic property in the relevant sense is, it includes this apple’s redness at t, my irritation last night upon reading your reply, and the moon’s having a certain mass; it might possibly include ways you can’t be (but might not?), could include intensional states like thinking Casey is innocent if we are talking about first-personal intensional states (but only if first-personal intensional states are intrinsic properties in the relevant sense), and possibly could include modal properties of a certain sort (but then again might not). I understand trying to be general enough that finer details in theories of properties, but this goes well beyond that into obscurity, and makes assessing self-evidence impossible.The vagueness about intensional and modal properties is especially worrying. Indiscernibility of identicals in the simple case (that summed up in what we usually think of Leibniz’s Law), while universal, necessary, and self-evident if we can rule out certain intensional and modal issues, is known to break down for unusual intensional and modal situations (as your post acknowledges); any assessment of the self-evidence of your alternative principle therefore requires at minimum a clear answer about what intensional and modal properties can be counted as relevantly intrinsic, if intrinsic properties of any sort are going to play an important role (which, from your response, apparently they are). It could make all the difference between a self-evident principle and a superficially plausible but definitely false one. Likewise, since discussions of the Trinity regularly appeal to intensional and modal properties, due to the influence of both self-knowledge and emanation models, it could make the difference between a self-evident principle that is problematic to a discussion of the Trinity and a self-evident principle that really isn’t.

You and I are both philosophers, so you should know where I’m coming from here. If someone claims a principle is self-evident and has no clear definitions to give, I have no choice but to call a foul. It comes with the territory.

Before I press the issue further. I’d like to hear a little bit more as to why (2) would be false if the argument used the names to refer to the same self.

Hey Dale, yes, I spoke with no context. I tried to expound upon Adam’s comment that T1 and T2 might not be identical. But if as you say that T1 and T2 are identical, then T in front of the mirror is identical to the T reflected in the mirror, regardless of electron and any other quantum rearrangement.

James – I don’t get the point of the mirror example here.

Adam,

The call older Dale “Dale1” and the younger Dale “Dale2”. Now, we agree that Dale1 = Dale2. Your worry is that my version of L’s Law is incompatible with that. But no, but Dale1 and Dale2 weigh 170 in 1990 and 200 in 2010.

(The mode here (z above) is weight – or maybe strictly it should be mass. The years are the w variable. Dale1 is x, Dale2 is y.)

Does that help?

Hi Smeagol,

Thanks for the comment.

So, it’s been a while since I saw those movies. This scenario, I take it, is Smeagol/Gollum arguing with himself; he’s conflicted in his motivations. And he dubs his loyal side by one name and his treacherous side be the other. Is that right?

I think if “Smeagol” and “Gollum” name a self, they name the same one, and so your premise (2) would be false.

If they name personalities of one self, then they are two of those, and (4) would be false.

Thus, I would say that your argument is unsound, however interpreted. Feel free to press the case if you want to.

How’s about this as a counter-example to your precioussss formulation, Dale:

(1) If Sméagol is Gollum then _being Master’s friend_ is a way Sméagol was that night in the wilderness if and only if _being Master’s friend_ is a way Gollum was that night in the wilderness.

(2) But, Sméagol was Master’s friend that night in the wilderness and Gollum wasn’t Master’s friend that night in the wilderness.

(3) Thus, Sméagol isn’t Gollum.

(4) Yet, obviously Sméagol is Gollum.

(5) Thus, either not (1) or not (2).

(6) Clearly, (2).

(7) Thus, not (1).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLvIFRNbqOs&feature=related

That is, But God judges me as if I were [the same person].

As I look into a mirror, the positions of some of my electrons drastically changed within the time that I see my reflection. At the subatomic level, I am not the same person in the mirror. But God judges me as if I were.

Dale,

I don’t follow. It seems to me that your principle very well could let me infer that you are not numerically the same as your slimmer, younger self just because t1 and t2 are not identical.

One other quick thought. Brandon, you’re certainly right that my W requires some explaining. I’m not too worried about it, though. If you want a L’s Law which has in the biconditional something like Fx < -> Fy – to really understand the principle, we must have the concept of a thing satisfying a predicate. My concept of a mode is about as basic as that, I think.

Hi Brandon,

Thanks for this; this is helpful. Here are some responses.

1. No, I mean universal quantification. I’m just specifying that W requires certain things.

Compare, expressing the symmetry of brotherhood like this:

(x)(y)(B(x,y) < -> B(y,x))

To stand in the brother of relation, one must be a human, and male. We could of course spell out these requirements in an extra clause (if x is a human and y is a human and x is a male and y is a male, then _) – but I don’t see why we must do that. If need be, I could bloat out my formula, specifying what sort of thing the w and z must be, but again, that seems needless, once W is explained.

About x and y – I’m assuming that restriction follows from the meaning of =. They just have to be individuals in the most minimal sense (they could belong to any category).

2. No clue? Brandon, that sounds a bit overblown. It includes this apple’s redness at t, your irritation last night upon reading my reply, the moon’s having a certain mass. A mode may be a way you can’t not be, or not. It your own intentional states (e.g. thinking Casey is innocent) are intrinsic, so modes of you, but other people’s are not modes of you. So it rules out pseudo-features like “being-thought-irritated-by-Dale”. So it gets around the apparent L’s Law counterexamples like the example in the post.

About modality – I think modes may be essential or not. I’m not able to think of any modal counterexamples. You?

The looseness in the interpretation of W was meant to allow people holding different theories of properties to sign on. So I could ask you: what do you call what I call “modes”? Then, if my principle is really neutral, I should be able to give you a version of it compatible with your own view of properties.

My examples so far have been where the bearer of the mode is plausibly a substance. But I don’t think I want to require that. I want “intrinsic” to be as neutral as possible as well. So suppose the x and y were rooms – not substances. The modes would be ways they are – something like, facts about each room which included nothing beyond the room. e.g. messy, stinky, dark

Now, we can actually infer that -(x=y) from differences in a lot of relations as well. e.g. being 3 ft. away from something. But I’ve restricted modes what is intrinsic because the intuition is especially strong in these cases, and to rule out counterexamples deriving from relations to thinking things. So this principle is a bit narrower than L’s Law is usually thought – it just specifies the sense of “indiscernibility” a bit more strictly.

3. I’m not sure why you think L’s Law has to be self-evident “for chiefly syntactical reasons”. L’s Law was never supposed to be an analytic truth. It was always based on the intuition that a thing can’t differ from itself. So I’m not sure why you think it is a problem that it’s a metaphysical principle. Of course it is. It may be, as I suggested last comment, that you’re just insisting the L’s Law be a substitution principle, and not a metaphysical one. I think Cartwright quite properly separates the two.

Please say what proposition you have in mind here.

“I scarcely even know where to start in order to assess such a principle”

Really? OK – let’s suppose it false. The antecedent will be true (x=y) and the consequent false. To make it false the “sides” of the biconditional must differ in truth-value. So we’re imaging that there’s one self-identical thing, and at some time, it is and is not intrinsically a certain way. Impossible, right? So, it’s a necessary truth.

I could spell this out in a formal argument… maybe I’ll do that later. Have to travel cross country today, and I’ve yet to pack!

As always, please argue back.

Then I have no clue what this self-evident principle is supposed to be. Given what you’ve just said, there are three things you need to explain before anyone can even assess the alleged self-evidence here.

(1) If w is only allowed to take “a date, point in time, period of time, or timeless eternity”, it’s incorrect to have the universal quantifier for w; you’re restricting quantification of w to specific domains, namely, temporal or quasi-temporal ones, and giving up the unrestricted formulation you actually gave. What is really doing the work, to the extent that w does any work, has to be the nature of these temporal or quasi-temporal conditions. I also have no idea why this (apparently) ad hoc condition is being tagged on: it’s something radically different from anything we get in Leibniz’s Law, and without an explanation it makes your claim that this is a self-evident principle much less plausible.

Ditto with restricting x and y to singular referring terms and names. Ditto with restricting z to “a mode, an intrinsic way something is, or if you like, a token property”.

Where is all this coming from? None of this was explained in the post.

(2) I have no clue what you mean by “a mode, an intrinsic way something is, or if you like, a token property” in this context; none of these have standard, consensus accounts, and just going on what you’ve said it looks very much like you are simply using it to rule out intensional contexts. Are you rejecting all intensional and modal properties as non-intrinsic? If not, what survives, and why?

(3) You originally seemed to suggest that lots of interpretations of W would work; you gave no indication that there was some special meaning that had to be given to it, beyond giving a general way of structuring the ordered triplet. That’s why I gave one that didn’t: it preserved the structuring and all the syntactic features. Your response shows precisely the problem here. If these things are relevant, it follows that your reformulation is not self-evident for chiefly syntactical reasons (which is usually the reason given for saying Leibniz’s Law is self-evident), but solely given a particular interpretation, or, at least, family of interpretations.

In other words, your response shows that any purported self-evidence here is not logical, but metaphysical — it’s intrinsic modes, temporal or quasi-temporal properties, and the necessary properties of what is identified by singular reference that are actually doing the work. The formula you’ve provided doesn’t contribute anything of significance; it just describes, at best, one purported implication of a set of purportedly self-evident principles governing the interpretation that you haven’t gotten around to explaining yet. And the particular metaphysical fields we get into immediately with your conditions are not ones where self-evidence is found on every corner. The logical expression wasn’t a problem — it is, in fact, self-evident and necessary where intensional and modal contexts aren’t in play, and so it was actually quite a plausible candidate for universal, necessary, and self-evident — add a few qualifications and it is. But I’m having a great deal of difficulty believing that there are any self-evident principles about the relation between identity of two objects of singular reference and the equivalence of all the intrinsic modes of the first object of singular reference under a temporal condition and the same intrinsic modes of the second object of singular reference under the same temporal condition. I scarcely even know where to start in order to assess such a principle, because it appears to get into metaphysical deep waters immediately.

Your whole post was an appeal to the reader: “you understand it, with a bit of effort, no? And so, does it not have that obvious shine of truth”. To which the answer is, it would seem, no; you haven’t given us enough to understand it even with effort, and so far there’s no obvious anything about it. You’ve been very vague about precisely that which the self-evidence has to be founded on. You’ll have to be a lot more expansive for us stupid people.

Brandon, as always, thanks for the comment.

I see that I wasn’t as clear about the interpretation of W as I should have been.

(w)(x)(y)(z) ( x = y -> (W(z, x, w) < -> W(z, y, w))

The third place in W(_, _, _) – filled by the variable w above – can only be filled by a date, point in time, period of time, or timeless eternity. The “at” was temporal, or quasi-temporal. This limits considerations to a single time or quasi-time.

Adam – that is how my formulation is built to allow the possibility of intrinsic change. Yes, I agree that we must allow for intrinsic change, particularly in the cases of ourselves.

Brandon, I think you read the third place in W as having to do with a means, or something.

Another problem with your counterexample is that the first place in W (z above) must be a mode, an intrinsic way something is, or if you like, a token property.

Another problem is that x and y must be singular referring terms or names. (x=y means that x just is y, not that “x” and “y” co-refer.) But your counterexample has descriptions which might be satisfied by a gazillion people.

In the last part of your comment, you seem concerned about the interpretation of W. But since it’s my formulation, and I’m simply trying to capture a necessary truth, I think I can specify the meaning of W however I see fit. I’m not claiming that the sentence above expresses a truth however interpreted.

Please do take another crack at breaking it. For myself, I don’t see “the general problem of intensional equivalence-breaking”. I think one has to take care to not interpret this as a substitution principle…

As with the original Leibniz’s Law, your version seems to admit of counterexamples in intensional or modal contexts, although necessarily more complicated ones. Consider the case where x=person whose name is Mark Twain, y=person with the name Samuel Clemens, w= the list of people whose names John thinks might be real authors , z=person who wrote Tom Sawyer.

If W is the property of the ordered triplet being such that ‘John recognizing the second on the basis of some reason or other as having something do with the third’ makes it so that John includes the second in the first, your principle then seems to tell us that:

Mark Twain is only the same as Samuel Clemens if: John’s recognition with respect to Mark Twain (i.e., the recognition on the basis of some reason or other that Mark Twain has something or other to do with the person who wrote Tom Sawyer) makes it so that John includes Mark Twain on the list of people he thinks might be real authors whenever John’s recognition with respect to Samuel Clemens (i.e., the recognition on the basis of some reason or other that Samuel Clemens has something or other to do with the person who wrote Tom Sawyer) makes it so that John includes Samuel Clemens on the list of people he thinks might be real authors, and vice versa.

This, however, is not only neither necessary nor self-evident: it is obviously false. John might well recognize that both Mark Twain and Samuel Clemens have something or other to do with the person who wrote Tom Sawyer, but it doesn’t follow that this will lead him to put both on the list of people he thinks are real authors. He might, for instance, have been correctly told that Mark Twain is the author of Tom Sawyer and incorrectly told that Samuel Clemens was a person Mark Twain associated with who wrote no books.

So your principle seems to run into the same general problem of being susceptible to intensional and modal counterexamples. What is really doing the work here (as far as necessity and self-evidence go) is the interpretation of W. Under certain interpretations of W, the principle obviously is necessary and self-evident; under modally or intensionally complicated interpretations of W, it can admit of counterexamples. You could complicate the formula as much as you wish, using ten thousand variables if you wish; any formula establishing an implication with an identity in the antecedent and a simple extensional equivalence in the consequent will admit of intensional or modal counterexamples, because intensional and modal contexts will always allow for the left-hand side of an identity equation to be given a different intensional or modal property than the right-hand side of an identity equation, thus breaking the equivalence in the consequent. Adding more variables means that examples of this fact become more complicated, but nothing else; the same thing that mucks up the base case will muck up any formula of the same general type, and for exactly the same reason. All new variables can simply be placed in the parentheses in the above Mark Twain counterexample, leaving the basic problem exactly as is.

At least, I see nothing in your principle that protects it from the general problem of intensional equivalence-breaking; all you’ve shown here is that you can avoid the simplest counterexamples by complicating the formula.

Hi Dale. I am thinking about your version of LL and I think I get it. But I get lost when thinking about how we persist through time. It seems to imply that I am not numerically the same person I was last year–or at least it is compatible with the idea I am not the same person as last year. It seems to just say things are identical with themselves at some time t. At a later time t2 I am the same as I am at t2, but who cares? Aren’t we interested in whether we are the same at t1 and t2?

Hi Victor,

If you could develop your belief in an article so others could more clearly evaluate your belief, then it would be a useful article. 🙂

I believe, Christ is a full representation of God, in the same sense as an infinite sequence of digits is a representation of a real number. But the question whether an infinite sequence of digits is the same as a real number is meaningless. The answer depends on our definition of a real number which may vary. In the same way the question whether Christ is God is meaningless. Every property of God is represented as a property of Christ, but these two properties (of God and of Christ) are sometimes different. That God has a son is property of God which is represented as some other (I’m not sure which) property of Christ. There are no contradiction in my theology.

Well, should I write a detailed blog post on this issue? But why, is this philosophy useful for people at all? It is just true.

The working title is “Language and the Structure of Berkeley’s World.” I am trying to argue that Berkeley’s views on language (both human and divine) can help solve the problem of how a world made of fleeting ideas can have the sort of structure commonsense attributes to the physical world.

James – you’re welcome!

Kenny – that’s great. You’ll learn a ton from JVC. He was the one who really helped me to understand certain logics (modal, temporal), and helped me develop the patience to wade through various parts of the literature. Great guy, first rate philosopher. What’s your general topic in Berkeley?

Hey Dale, Thank you. I recall on your blog’s 5th birthday that you requested ideas and I replied with a request for more articles about identity, and you responded with this excellent series. 🙂

Yes, the first time I heard about the monothelite controversy, I couldn’t get my head around how anything with two wills could possibly be one person. The actual text of the council doesn’t address this, but it’s pretty clear from other theological writings that they mean two faculties or capacities of willing, and this I can make some sense of. In fact, it does seem to me to follow from Chalcedon, for if Christ is really to be human, he must move his arm the same way I move my arm, and not by an exercise of omnipotent power. Without a human will, it seems that we would end up conceiving of Jesus as like a remote-control robot being operated by God, rather than as a human (and divine) person.

BTW, I’m starting dissertation work on Berkeley this fall, supervised by Van Cleve.

Nice comment, Kenny.

Yes, a later ecumenical council declared the incarnate Son to have two wills. This is something that surely comes as a shock to your average Bible reader, as much as if someone asserted Jesus to have four arms. Of course, they inferred that from the earlier creedal requirement that Jesus had “a complete human nature” as well as “a complete divine nature.”

As you point out, this doesn’t mess up my example, for the two will still be seen to differ in that scenario. That’s why I think it’s a good example – it is common coin to those in this debate, and doesn’t beg any questions.

PS – I see you’re at USC now. Sweet!

Your Gethsemene example is a little complicated. According to the orthodox (conciliar) Christology, as far as I can understand it, Christ both wanted and did not Christ to be crucified. Specifically, it is held (again, if I understand correctly) that the single person, Christ, has two volitional faculties, the single divine volitional faculty which he shares with the Father and the Holy Spirit, and an ordinary human volitional faculty just like ours. It seems that with the former he wanted the crucifixion, and with the latter he wanted to avoid it (though the claim of moral perfection is supposed to mean in part that the human will always ultimately submitted to the divine will rather than clashing with it, so we are talking about mere wants as opposed to decisions here).

Anyway, having a human volitional faculty and wanting, according to his humanity, to avoid the cross, and even becoming incarnate can all be truly predicated of the Son, but not of the Father or the Holy Spirit or, for that matter, the Trinity, and none of them seems to be able to be dealt with by complications about time or about opaque referential contexts. (Besides, it seems to me that trying to deal with such things by means of opaque referential contexts would amount to Sabellianism.) So we clearly can’t say ‘the Father is God’ and ‘the Son is God’ both with the ‘is’ of (numerical) identity. Fortunately, there seems to me to be very little evidence that historical Trinitarianism was intended this way, except perhaps by the (rather confused) author of the ‘Athanasian’ Creed. Leibniz wasn’t the first to discover Leibniz’s Law.

Comments are closed.