I opened up Facebook this morning and saw this short video by L. Bryan Burke:

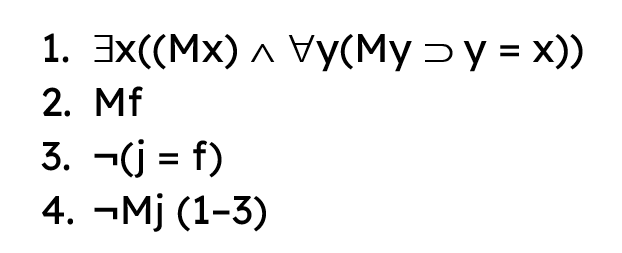

Is this a logically valid argument? (That is: does the conclusion follow from the premises?) And is it a sound argument? (That is, is it valid and has only true premises, which means that the conclusion must be true as well?) Yes, it checks out. Here is how we symbolize the argument in predicate logic.

The part in parentheses in his step 1 (that this one’s name is “Yahweh”) is unnecessary to get the conclusion, so I’ve left it out of the analysis. The argument has only four steps, three independently-justified premises (1-3) and a conclusion which is implied by them (4).

- Step 1: M_ means that _ has this quality: Most High God. In English 1 says: There is an x such that x is Most High God and for any y, y is Most High God only if y = x. (In other words, there is at least one Most High God, and there is at most one Most High God—in other words, there is one and only one Most High God. Justification: monotheism—if there is only one god there is only one with this quality: Most High God.

- Step 2: f = the Father. So 2 says: The Father is Most High God. Justification: clear implication of NT texts: Mark 5:7; Luke 1:32, 35, 8:28.

- Step 3: 3 says: It’s not the case that Jesus and the Father are one and the same. Justification: trinitarian traditions (the anti-modalist clause that the Son and the Father are numerically distinct) and/or the fact that according to the NT Jesus and the Father have simultaneously differed, e.g. on a particular Friday night Jesus was dead while the Father was alive. It is self-evident that one and the same thing can’t at one time differ from itself. See here.

- Step 4 (conclusion): 4 says: It’s not the case that Jesus is Most High God. This follows from 1–3; if there is one and only one Most High God (premise 1) and this is the Father (premise 2) and Jesus is numerically distinct from the Father (3), it follows that Jesus is not Most High God. Exactly how we would derive 4 from 1-3 depends on the exact system of logic; I haven’t spelled out those extra steps, since we can all “see” that if 1-3 are true then 4 is true.

Let me then restate the argument in something resembling normal English:

- One and only one has this quality: Most High God.

- The Father is Most High God.

- It’s not the case that the Father and Jesus are one and the same; OR, the Father and Jesus are two.

- Therefore, it’s not the case that Jesus is Most High God.

4 follows from 1-3 (so it’s valid), and each of 1-3 has ample biblical justification. A Christian should endorse this argument as sound. Well done, Bryan!

What’s a trinitarian to do, when faced with this argument? It’s going to depend on what Trinity theory one has placed their hope in. Some would redefine “monotheism” and on that basis deny 1. Others would deny 2, on the grounds that only the Trinity, which is the one God, is Most High God.

Both moves go against clear scriptural teaching. About denying 1: the Old Testament says Yahweh is Most High God and that he’s unique, being the only god. But then, he will be the x in premise 1, and premise 1 will be true! About denying 2, this is to disagree with the cited New Testament texts. Jesus is the Son of the Most High God. Who is that? Obviously, the Father–that’s who Jesus is the Son of. Hence premise 2.

(There are other trinitarian moves that are possible, but I think they are ones only an analytic philosopher could love, e.g. denying premises 1 and 3 because they employ the concept of non-relative numerical identity, assuming the implausible thesis that identity must be sortal-relative.)

This argument is one of a number of ways one can show that trinitarian traditions clash with clear biblical teachings. Here’s another. And there are other ways too which I haven’t got around to publishing.

A Trinitarian would say that “1” represents the divine essence, which enables F & S to be MHG while being different from each other. As an analogy, a cat’s skeleton is feline, and its flesh is feline, but the skeleton and flesh are different from each other.

Their argument doesn’t work, but your piece doesn’t even contemplate their answer (which I’ve commonly encountered in the blogosphere).

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the comment. If the thing which is the unique Most High (per premise 1) is the divine essence, and that is something numerically distinct from the Father, then they would be denying 2.

That seems a bad move. It’s quite clearly taught in the OT that Yahweh is the unique Most High, and it’s about as clearly taught in the NT that this same one is now called “the Father,” “God the Father,” or just “God.” But then, the Father is the Most High God, being one and the same with Yahweh. So if the divine essence is distinct from him, this rules out the divine essence being the Most High God. If the divine essence is just the features that makes God a god, then we should say it is not one and the same with him, as God is neither a feature nor a group of features.

The cat retort you report is from William Lane Craig, expounding his “Trinity monotheism” in his co-authored book Foundations for a Christian Worldview. Oddly, he has since changed that theory significantly; see the recent debate book that he’s in with me and two others. His point is that the Persons of the Trinity can be “divine” in some literal and important sense even if that sense does not imply being a god; he wants to say that the only God is the Trinity – and so none of the persons has *that* kind of divinity / is “divine” in that sense. This goes against catholic traditions; but he’s willing to do that.

Thanks for replying to my post, Dale. I agree that no trinitarian solution can work. However, I don’t think that any Trinitarian would say that the divine essence is “numerically distinct” from its instantiation, excepting, perhaps, a Christian Platonist. As a concept, essence is abstract but is objectively real in its exemplars. As you note, this isn’t quite what Craig is getting at, and if logically extended, it results in three gods. But the point is that multiples can participate in X and be recognized as “fully X” without diminishing another’s identity as X in a predicative manner.

With respect to Craig’s earlier feline appeal, he also used it as a predicate, so that one can say that the skeleton is “fully” feline (we wouldn’t say that it was partially feline just like we wouldn’t say that our heart is partially human—it’s fully human). But since this is clearly the partialism that was condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council, that’s a bridge too far for most Trinitarians.

Nonetheless, since all versions of the Trinity, including those affirming divine simplicity, cannot avoid composition in the Godhead, and since all composites are caused and dependent, no version escapes effective atheism. I realize you’re not a classical theist such as myself, but that’s how I see it.

> Jesus is the Son of the Most High God. Who is that?

the trinity

which i guess makes him in some sense partly the son of himself…?

that doesnt seem to work…

Comments are closed.