In the last two posts, I looked at Athanasius view that the Father begets the Son much like how human fathers beget human sons. But Athanasius’ view raises some interesting questions.

One of the things Athanasius likes about natural procreation is that sons get their natures from one of their ingredients, namely the substance they get from their fathers. For example, in God’s case, the Father is an ingredient in the Son, and the Son inherits his divine properties from that ingredient. However, the Son is not identical to the Father, and it’s not clear to me how the Son is supposed to ‘inherit’ properties from something he’s not identical to.

Consider an analogous case: a statue and the bronze it’s made from. Bronze statues, after all, inherit certain properties from their bronze. For instance, a statue has a certain size, shape, and mass because it’s made from a lump of bronze that has that size, shape, and mass. If we can explain how statues inherit properties from their bronze, then maybe we can explain how the Son inherits properties from the Father.

For convenience, let’s call the statue ‘Athena’, and let’s call the bronze ‘Lumpel’. According to what I will call the ‘standard view’ of material constitution, Lumpel and Athena are two numerically distinct, non-identical objects that share the same material parts (at some level of decomposition), and which coincide in the same region of space.

Now, there are certain properties that Lumpel and Athena do not share. For instance, they don’t share their kind-properties. Lumps of bronze are not the same kinds of things as statues. Nor do Lumpel and Athena share their modal properties. For example, lumps of bronze can survive being melted down and recast, but statues cannot.

But there are other properties that Lumpel and Athena do share. (And here I’m not talking about any of the properties that Lumpel and Athena share with everything. I’m only talking about properties that they share in virtue of the fact that they coincide.) For example, since they share the same material parts, Lumpel and Athena share material properties like size, shape, and mass. Similarly, Lumpel and Athena exist together for a period of time, so they share certain temporal properties too.

On this view, when we say x inherits a property from y, what we mean is that x and y share a property in virtue of the fact that they coincide.

How does this help with the Trinity? One of the questions I have is this: what explains why coinciding objects share certain properties but not others? I think most would say that coinciding objects share certain kinds of properties because they share certain kinds of parts.

For example, Lumpel and Athena share material properties because they share material parts. But we could also say the same thing about temporal parts too. The first quarter and the first half of a Notre Dame football game share certain temporal parts, and that’s why they share certain temporal properties.

Similarly, maybe we could put this to work in the divine case. If we say that the Godhood is like a divine ‘part’, then maybe we could say that coinciding persons who share that divine ‘part’ would also share divine properties. Of course, the Father and the Son share the Godhood (for the Father just is the Godhood, and the Son has it as one of his ingredients), so they would share divine properties too.

Before this strategy could be successful, we’d still have to answer more questions. For one thing, this strategy construes the Godhood as a ‘part’ rather than a constituent, and it’s not obvious that parts are related to their wholes in the way that constituents are related to what they constitute.

Consider Lumpel and Athena again. Now, it’s not exactly clear what Athena’s parts are (perhaps it’s her particles, perhaps it’s her arms, legs, and the like), but whatever they are, is Athena related to them in the same way that she’s related to Lumpel? And in the divine case, is the Godhood more like the particles (or arms, legs, etc.) that Athena is composed of, or is the Godhood more like Lumpel?

Whatever we might want to say about these questions, if we claim that coincident objects (or persons) share certain kinds of properties because they share certain kinds of parts, then we’ve only identified the conditions for shared properties. We haven’t really explained how those properties are shared.

To see this, consider the following question. When we say that Athena and Lumpel share certain properties, what exactly do we mean? Do we mean that those properties are instantiated twice — once in Lumpel, and once in Athena?

If so, then suppose that Lumpel and Athena share the same weight: e.g., 10kg. If this were instantiated twice, then Lumpel would be 10kg, and Athena would be 10kg too. But then the total weight should add up to 20kg, which of course seems odd, because our scales only show a total weight of 10kg.

On the other hand, if Lumpel’s and Athena’s shared properties are not instantiated twice, then they must be instantiated once. So what would they be instantiated in? In Lumpel, or in Athena? Either way, one of the two wouldn’t have a weight, and that seems odd too.

Perhaps one might say that, strictly speaking, shared properties are instantiated in neither Lumpel nor Athena, for properties don’t ‘inhere’ in subjects at all. Rather, what it means for a property to be instantiated by something is just for that property to ‘occur’ in that particular region of space.

But Lumpel and Athena both occur in the same region of space, and so all their properties occur in that same region of space too. Wouldn’t all their properties then be shared? That would lead to contradictions. For instance, Lumpel can, but Athena cannot, survive being melted down, so Athena and Lumpel could not share those features without contradiction.

Now transfer all of this over to the Trinity. When we say that the Father and Son share divine properties, are we saying that those properties are instantiated twice — once in the Father, and once in the Son? Surely that would entail that there are two (coincident) Gods, and I just can’t see Athanasius agreeing to that.

On the other hand, if we think that shared properties are only instantiated once, then who would those properties belong to? The Father, or the Son? Either way, one of them wouldn’t be divine, and Athanasius wouldn’t agree to that either.

Alternatively, if we think that properties don’t ‘inhere’ in subjects but rather simply occur in a particular region of space, then wouldn’t the Father and Son share all their properties? That would lead to contradictions. For example, the Son is begotten and the Father is not, so the Son couldn’t share the Father’s unbegotteness. (I’ll return to this point in a moment.)

Perhaps we could offer Athanasius some help by suggesting that he takes a view where, say, Lumpel and Athena are numerically the same, but not identical. On this view, the Father and the Son would be numerically the same, but not identical, and so there would be one God there, not two, without the Father and Son being identical. Surely that’s just the sort of thing Athanasius is after.

Whatever the merits of this strategy, I still have similar questions. In what sense are divine properties shared? Would it even make sense to say that they’re instantiated twice? I wouldn’t think so, for the Father and Son are one, and presumably their shared properties only occur ‘once’ in some sense too.

But if these shared properties are not instantiated twice, then who or what do they belong to? The Father? The Son? Neither? In what sense, exactly, are these properties shared? And when we say something like ‘the Son is omnipotent’, do we just mean that ‘the Son is numerically the same as, but not identical to, something that is omnipotent (viz., the Father)’?

I’m not suggesting that these questions can’t be answered. On the contrary, I’m sure they can. Here, I’m just pushing for a more detailed metaphysical account of how, precisely, these properties are shared, and asking these sorts of questions is one way of getting our minds to start thinking about that. For the time being, however, it’s not clear exactly how or in what sense Athanasius thinks the Father and Son are supposed to ‘share’ properties.

In the next post, I want to turn to another problem Athanasius faces.

Pingback: trinities - Arius and Athanasius, part 10 - The Father and Son can’t share all their properties (JT)

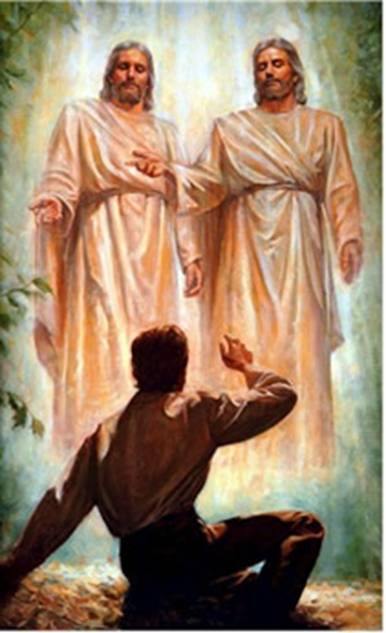

Doh! I just figured out that you’re refering to the picture. Right, right, right, right (as Seinfeld says).

You aren’t suggesting that Athanasius and Joseph Smith are numerically the same but not identical?

Comments are closed.