Negative Mysterianism Explained

It’s all so clear now! Happy April Fools Day! (A link for those confused about the subject line.)

Dale Tuggy (PhD Brown 2000) was Professor of Philosophy at the State University of New York at Fredonia from 2000-2018. He now works outside of academia in Middle Tennessee but continues to learn and podcast.

It’s all so clear now! Happy April Fools Day! (A link for those confused about the subject line.)

Here’s sound advice for non-philosophers, including theologians, who are interested in philosophy, in an interview with distinguished philosopher Timothy Williamson. The interview starts slowly, but gets interesting when Williamson recounts his experiences with “continental” philosophy. He also addresses a pervasive confusion, common in discourse outside analytic philosophy, between truth and certainty.

Call me a satisfied customer – I had a great time at the Eastern Regional Conference of the Society of Christian Philosophers this weekend. Thanks to Patrick Toner and Wake Forest University for their great hospitality! The program was very strong. To mention just a few sessions: Paul Herrick present a paper analysing and endorsing Richard of St. Victor’s main argument for the Trinity, and… Read More »Eastern SCP report (Dale)

It seems I touched a nerve, judging by the word count so far (here, and here). First, let me make clear that I have no interest in mocking Catholic doctrine. I’m a non-catholic (and so non-Catholic) Christian, and am in sympathy with the Catholic tradition in many ways. I’m going to avoid some well-worn Catholic-Protestant battle areas here, and try to stick to what I… Read More »More on Loyola’s “white is black” passage

Philosophy Compass is a unique philosophy journal which only publishes survey articles, pieces which aim to summarize recent work. Its aim, as editor Brian Weatherson explains, is to enable people to keep up with a vast, overspecialized, fast-moving, and only somewhat accessible world of philosophical research. What’s more exciting – they sell the pdfs of the articles for $1.99. They’re trying to be the iTunes… Read More »Robin Le Poidevin on metaphysics and the Incarnation @ Philosophy Compass

St. Ignatius Loyola (1495-1556) founded the Jesuit order and authored a famous book of Spiritual Exercises. There, in a list of rules for correct belief, we have this: Thirteenth Rule. To be right in everything, we ought always to hold that the white which I see, is black, if the Hierarchical Church so decides it, believing that between Christ our Lord, the Bridegroom, and the… Read More »Loyola: tradition trumps sense perception

Philosopher Graham Priest is notorious for his claim that there are true contradictions. I have to confess that when I first heard this years ago, I thought the people telling me were pulling my leg. But, they were not. Priest is deadly serious, and has developed paraconsistent logics – logical systems which allow some true contradictions. And he’s vigorously defended his claims against all comers, as in this recent book.

Philosopher Graham Priest is notorious for his claim that there are true contradictions. I have to confess that when I first heard this years ago, I thought the people telling me were pulling my leg. But, they were not. Priest is deadly serious, and has developed paraconsistent logics – logical systems which allow some true contradictions. And he’s vigorously defended his claims against all comers, as in this recent book.

No, he doesn’t say that all contradictions are true – only some of them. And the ones which are true are also false. He claims that this thesis of dialetheism solves the liar paradox and others.

Very rarely, some theologian will come along, and assert that the Trinity doctrine is a true contradiction – not a merely apparent contradiction, but a real one.

Most Christians, though, eschew such a claim. Mysterian James Anderson discusses and rejects this approach to Christian mysteries in his book Paradox in Christian Theology.

Much to my surprise, I recently found a move like Priest’s in Gregory of Nazianzus (d. c. 390), in his Third Theological Oration.

Gregory is considering an argument by Arians, a premise of which is that the Son who the Father begot either was or was not in existence – I take it, prior or “prior” to his being begotten. (It is clear at the end of this section that Gregory takes them to mean literally before.)

Gregory asserts that this claim “contains an absurdity, and not a difficulty to answer.” He then gives a non-too-clear time example, which I’ll skip. Then he argues,

…in regard to this expression, “I am now telling a lie,” admit one of these alternatives, either that it is true, or that it is a falsehood, without qualification (for we cannot admit that it is both). But this cannot be. For necessarily he either is lying, and so is telling the truth, or else he is telling the truth, and so is lying. What wonder is it then that, as in this case [of the liar paradox] contraries are true, so in that case [concerning the Arians’ premise above] they [i.e. both alternatives] should both be untrue, and so your clever puzzle prove mere foolishness?

I take it that the “contraries” he mentions would be: “the man is lying” and “the man is telling the truth”. Contraries are often defined nowadays – I’m not sure how they were defined in his day – as claims that can’t both be true. But here, Gregory asserts that both are trueRead More »Gregory of Nazianzus – an early dialetheist? (Dale)

What I call positive mysterianism about the Trinity is the view that the doctrine, as best we can formulate it, is apparently contradictory. Now many Christian philosophers resort to this in the end, but only after one or more elaborate attempts to spell the doctrine out in a coherent way. On the other hand, some jump more quickly for the claim, not really expanding on or interpreting the standard creedal formulas much at all. These are primarily who I have in mind when I use the label “positive mysterian”.

I ran across a striking version of this recently, in a blog post by theologian C. Michael Patton, who blogs at Parchment and Pen: a theology blog. In his interesting post, he says that all the typical analogies for the Trinity (shamrock, egg, water-ice-vapor, etc.) are useful only for showing what the Trinity doctrine is not.

This contrasts interestingly with what I call negative mysterians. Typically, and this holds for many of the Fathers, as well as for people like Brower and Rea nowadays, they hold that all these analogies are useful, at least when you pile together enough of them, for showing what the doctrine is. Individually, they are highly misleading, and only barely appropriate, but they seem to think that multiplying analogies like these results in our achieving a minimal grasp of what is being claimed. Maybe they think the seeming inconsistency of the analogies sort of cancels out the misleading implications of each one considered alone.

In any case, in Patten’s view, the best you can do is to Read More »Mysterians at work in Dallas

Over at the Maverick Philosopher, Bill Vallicella and some others have been on a tear of philosophical theology, specifically on appeal to mysteries in theology, and on incarnation issues. Here, atheist philosopher Peter Lupu mounts an argument against positive mysteriansism. Bill asks: Does inconceivability entail impossibility. (No.) And: Whether Jesus exists necessarily? (No.) In another post, Bill argues that if a mysterian defense works for… Read More »Linkage: Mavericking Mysteries

Thanks to Ed Feser for some interesting dialogue on the topic of mysteries in Christian theology. This post is just a bunch of miscellaneous responses to his thoughts posted last week, here and here. As he mentioned, Ed and I knew each other briefly as students at what is now called Claremont Graduate University. I remember having a conversation in his car once, maybe around… Read More »More on Mysteries

At his self-titled blog Edward Feser, the Catholic philosopher & popular author mounts a negative mysterian defense of the Trinity. It’s worth a read. In my view, most of it is perfectly reasonable, but it goes wrong where he claims that the teaching of Christ as recording in the New Testament logically implies the creedal formulas about the Trinity. The defense of mystery appeals by… Read More »Feser’s Negative Mysterian Defense of the Trinity

In a well-argued recent guest post and follow up comment, Greg Spendlove argued that for all we know, there could be a property (feature) which is also a person / self / personal being. As I explain in my comments there, I’m not convinced – I think we’re on firm ground to deny the alleged possibility, but I loved his example of Hooloovoo – author… Read More »Linkage: Disproving the existence of Hooloovoo?

Thanks to Vlastimil Vohánka for referring us to this discussion between Maverick Philosopher Bill Vallicella and Dr. Lukas Novak of Charles University, Prague. As I understand it, a suppositum is supposed to be an ultimate subject of characteristics / properties, as distinct from non-ultimate subjects. My individual human nature is supposed to be suppositum, but Christ’s is not. One ought to be a little suspicious… Read More »Linkage: Vallicella and Lukas on Supposita

Last time I tried to analyze Richard’s argument in ch. 22 that his view preserves monotheism. This time, I critically evaluate the argument. Is it sound?

Last time I tried to analyze Richard’s argument in ch. 22 that his view preserves monotheism. This time, I critically evaluate the argument. Is it sound?

It goes like this:

What shall we make of this argument? Why believe premise 1? Richard says,

…if it is agreed that omnipotence can do everything, it will be able to carry out with ease what any other power would not be able to do. For this reason it is clear that only one omnipotence can exist. (ch. 22, p. 394)

I have a couple of problems with this. Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 22 – part 2 (Dale)

Below is a guest post by Greg Spendlove, who is an adjunct philosophy instructor at Salt Lake Community College. He received his Master of Arts in Christian Thought with an emphasis in Systematic Theology and a cognate in Philosophy of Religion from Trinity International University in Deerfield, IL in 2005. His Master’s thesis was entitled “A Critical Study of the Life and Thought of Brahmabandhab… Read More »Guest Post: Greg Spendlove on Logos Christology

Has Richard, after these 21 chapters so far of Book III of his On the Trinity (De Trinitate) only succeeded in proving that there are at least three gods? In chapter 22, Richard argues for a negative answer.

Has Richard, after these 21 chapters so far of Book III of his On the Trinity (De Trinitate) only succeeded in proving that there are at least three gods? In chapter 22, Richard argues for a negative answer.

First, he refers back to the doctrine of divine simplicity, which is common coin for medieval theists, even, surprisingly, for trinitarians. This needs explaining nowadays – theists now tend to think of God’s nature as something he has, and of God as having, and not being, his attributes. Moreover, we tend to think that God has many attributes.

For a primer on divine simplicity, I can do no better than Bill Vallicella:

[According to this doctrine] God is radically unlike creatures in that he is devoid of any complexity or composition, whether physical or metaphysical. Besides lacking spatial and temporal parts, God is free of matter/form composition, potency/act composition, and existence/essence composition. There is also no real distinction between God as subject of his attributes and his attributes. God is thus in a sense requiring clarification identical to each of his attributes, which implies that each attribute is identical to every other one. God is omniscient, then, not in virtue of instantiating or exemplifying omniscience — which would imply a real distinction between God and the property of omniscience — but by being omniscience. And the same holds for each of the divine omni-attributes: God is what he has. As identical to each of his attributes, God is identical to his nature. And since his nature or essence is identical to his existence, God is identical to his existence. (William Vallicella, “Divine Simplicity”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Richard starts ch. 22 by gesturing back at book I of De Trinitate – his point is that this divine being/essence/nature common to the three is utterly simple. Yet he realizes that this by itself won’t soothe the concern about monotheism. How can we rule out that there are three gods, each of which has is an utterly simple, composition free being? Then he hits on an additional argument.Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 22 – part 1

In the preceding chapters, Richard has been arguing for the impossibility of only one divine person. If there’s one, there must be more than one; more than that, there must be at least three.

In the preceding chapters, Richard has been arguing for the impossibility of only one divine person. If there’s one, there must be more than one; more than that, there must be at least three.

To do this, he’s used Anselmian perfect being theology – arguing that since God is absolutely perfect, and it would add to his perfection to have certain features, he must indeed have those. It seems that he prefers a three parallel arguments, from perfect goodness, perfect happiness, and perfect glory. (See, e.g. chapter 5.)

As the book goes on, though, it seems to me that he prefers the argument from happiness. Here, in chapter 21, he sums up his case, because he feels some pressure here at the end of the book to explain why all this should be considered monotheism, and not polytheism. More on that next time. Here’s what looks like his summary of his argument:

The fullness of supreme happiness requires fullness of supreme pleasure. The fullness of supreme pleasure requires fullness of supreme charity. The fullness of supreme charity demands fullness of supreme perfection. (p. 393)

This last part isn’t easy to see, but as we’ve been over it, I let it go here. In chapter 21, Richard assumes that perfect being reasoning should be applied to each member of the Trinity. If we do this, then we prove the existence of equally perfect beings, such that “all coincide in supreme equality. In all of them there will be equal wisdom, equal power, undifferentiated glory, uniform goodness, and eternal happiness…” (pp. 393-4, emphasis added)

This, he asserts, meets the requirement of the “Athanasian” creed,Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 21 (Dale)

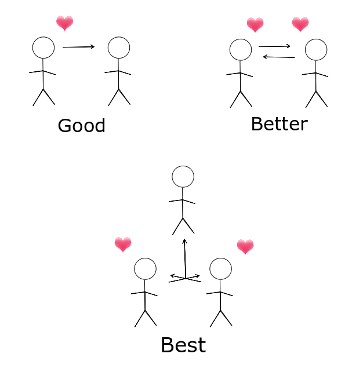

As Joseph explained in his last post, in his On the Trinity, Richard of St. Victor asserts the superiority of “shared love” (Latin: condilectus). He holds that it is superior to other loves in value and in the pleasure it involves. He’s imagining something like my chart on the left.

As Joseph explained in his last post, in his On the Trinity, Richard of St. Victor asserts the superiority of “shared love” (Latin: condilectus). He holds that it is superior to other loves in value and in the pleasure it involves. He’s imagining something like my chart on the left.

Look at the bottom case, and how the love arrows combine; this seems to be what Richard is imagining (see the quote in the last post). I don’t think it’s coherent, really – affections, or individual love-acts can’t literally fuse. Nor do I understand any non-literal way they can be said to “fuse”.

Still, I’m inclined to agree with Joseph and with Richard Swinburne that there is a unique value in lovers cooperating to love a third party. This is something we recognize, I think, in Mom and Dad’s love for junior, or even in “best friends” graciously including an excluded girl within their circle.

Further, I think Richard of St. Victor is right that there is a relational harmony and cooperation in such cases, and a unique sort of pleasure all around.

Whether this value would provide a perfect person with a compelling reason to create mysteriously originate at least two other divine persons is a further matter.

In chapter 20, Richard makes clear that my chart here is too simple – there should be aRead More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 20 (Dale)

Some good stuff from philosophical theologian Paul Helm at his blog Helm’s Deep. Among other things he criticizes this book by Alister McGrath. My favorite quote: …there is some confusion between affirming the logical consistency of the mysteries of the faith, and showing that they have not been proved to be inconsistent, and demonstrating their consistency.

Note: this review originally appeared in Religious Studies Review. FAITH LACKING UNDERSTANDING: THEOLOGY ‘THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY’. By Randal Rauser. Colorado Springs, CO: Paternoster, 2008. This rausing little book is a work of popular philosophical theology which exhibits uncommon intellectual honesty, courage, humor, clarity, and insight. Each chapter but the first is devoted to a doctrine of the Apostles’ Creed: Trinity, Creation, Incarnation, Atonement, Ascension,… Read More »Book review: Randal Rauser’s Faith Lacking Understanding