|

Listen to this post:

|

At his blog Dr. Michael Bird has a lengthy and informative post on the views of Justin Martyr, someone I’ve been reading for a long time. He’s trying to get Justin right; he’s going far beyond the average Internet apologist who notes that Justin calls the Logos “God” and spikes the ball, thinking this is an example of early trinitarian-style belief in “the deity of Christ.”

While most of what he says is right, the piece is not without its serious missteps, ones which I suppose are caused by Bird’s adherence to a Nicene or catholic narrative about the history of theology. First, a pedantic point. He writes,

There is an intensification of Logos christology among the early apologists especially with Justin Martyr.

Well, depending on what you mean by “Logos christology,” it may start here with Justin. But Dr. Bird wants to start it with the fourth gospel – that’s another argument. But let me just say, this scheme whereby God always deals with the cosmos through this second and lesser god – this does seem to start (in Christian theology) with Justin, and all the slightly later “logos theologians” have read him.

Second, Dr. Bird seems to want Justin’s Logos to be fully divine – like, divine in the way the one God is divine. After all, if this is (as he thinks) clearly and undeniably taught in the New Testament, you wouldn’t think that Justin would be going off track around the middle of the 2nd century. You can see Bird reaching towards a fully divine Logos here:

The center of gravity in Justin’s christology is to argue for a God beside God the Father, a first Power, the first-born and only-begotten Son of the unbegotten Father, the Logos who is Christ…To that end, we can detect a very strong sense of divinity attributed to the Logos. The “Logos is divine”…he was pre-existent before creation and “already existed as God”… The Logos is “the son of the true God” …and is worshipped …Even so, the Son is not the Father, but the Father has always had a Son, the “first-born Logos of God, is also God”…Justin’s analogies for Christ’s divinity vis-à-vis God the Father are like a thought from a mind or a fire kindling fire. Jesus is begotten from the Father, not an excision (apotome) of his essence (ousia)…Jesus is distinct in number, but not in substance (Dialogue 56.11; 128.4; 129.3). Eric Osborne sums it up: “The word is God’s first-born, God himself, God to him in number, but one with him in essence.”

A “very strong sense of divinity”? Perhaps in a sense. But notice, not enough to make him the same god as the Father or a “Person” in the one God. In Justin’s view, the Logos did exist “as a god” at the time of creation, but his view is that God brought the Logos into existence when the time was right to create – more on this below. What?! An “Arian” in the second century? Nah – not an “Arian.” But yes, he thinks that the Logos started to exist a finite time ago, that he was then caused to exist by God.

Does the Logos being God’s true Son mean that he’s fully divine? No – that idea is much later, being started by Athanasius in the 4th century.

Does the Logos being worshiped imply that he’s fully divine – no, just as Bird will shortly mention.

Does Justin’s fire analogy imply sameness of essence? No – look at the passages he cites (Dialogue with Trypo 61.2 and 128.4). His point is that in causing the Logos to exist, not using some pre-existing matter but just out of himself, God does not thereby lose some of his matter or substance. There is no, he says “abscission, as if the substance of the Father were divided.” (128.4) This seems to presuppose that God in some sense has matter, but at any rate, he doesn’t lose any in creating this Logos (or if you like, causing or begetting him), any more than a fire which kindles a fire thereby loses some of itself. But it doesn’t imply full divinity for the Logos.

Does Justin say that the Father has never lacked a Son? I don’t think so – I think Bird is mistakenly reading that later idea (Origen and beyond) back into Justin. To the contrary, God brought this Logos into existence by his own act of will (Chapter 76.1) “before all creatures” in the cosmos, “in the beginning of his ways for his works.” (Chapter 61.1, 61.3 Fall translation p. 94 – see also Chapter 129.3.) But then a moment before the Father (i.e. God) would have existed without having this Son, the Logos.

In sum, Justin doesn’t think, and Dr. Bird has not shown, that this Logos is as divine as the Father, i.e. the one God. This Logos is indeed “distinct in number” from God – i.e. not numerically the same thing/being – but nothing Justin says implies that their substance/essence, that is, their divinity, is the same. It couldn’t be, for this Logos is caused and fails to be eternal – and that’s just the start of why he can’t be fully divine, according to Justin.

Bird continues, seeming to concede that trying to find a fully divine Logos in Justin is hopeless:

Yet Justin also implies a certain subordination because God is unbegotten and everything after him is begotten and corruptive…and the Son holds “second place” with the prophetic spirit “in the third rank” (First Apology 13.3-4; 60.7).

Right – it’s part of the monotheistic concept of a god that such a being is underived; all else comes from him, but he is without any cause or origin. And note that the Logos’s subordination is, in current lingo, ontological, not merely functional. And the “second place” here is a second rank in honor, second to God, a silver medal. The Spirit gets the bronze medal (First Apology 13). Full divinity would entail being worthy of the highest honor, being held in first place; only the Father has this divinity and the honor it requires.

Bird continues,

Justin argues that the Logos is “another God and Lord under the Creator of all things, who is also called an Angel, because he proclaims to man whatever the Creator of the world— above whom there is no other God— wishes to reveal to them”…This angel “called God, is distinct from God, the Creator; distinct, that is, in number, but not in mind” (Dialogue 56.11).

Notice that in Justin’s view, there is a similarity or sameness between the one true God and this lesser deity the Logos. But it’s a sameness of purpose, aim – just as in John 10:30. He neither asserts nor implies nor assumes sameness of divine essence; he has no need to, and in fact given what full divinity implies, the Logos couldn’t have it. But sure, this Logos is called “God” and “Lord” (etc.) and is in some sense “divine.” But he’s not the Creator, the ultimate source of all else, but rather one who is brought into existence to be used by the Creator. (Second Apology 7) As in the Bible, Justin doesn’t assume that only a fully divine being could rightly be called “God.”

Bird continues,

A God beneath God is supported by way of citations to Psalms 45:6-7 and 110:1…Justin identifies God with the Angel of the Lord, this Angel with the pre-incarnate Christ, who appeared to Moses in the fire…

Correct. But Justin also thinks that full deity/divinity, the kind the one God (= the Father) has, implies a kind of transcendence that the Logos doesn’t and can’t have. After discussing some Old Testament examples of “God” interacting with people on earth, Justin says this:

…you should not imagine that the Unbegotten God himself went down or went up from any place. For, the ineffable Father and Lord of all neither comes to any place, nor walks, nor sleeps, nor arises, but always remains in his place, wherever it may be, acutely seeing and hearing, not with eyes or ears, but with a power beyond description. Yet he surveys all things, knows all things, and none of us has escaped his notice. Nor is he moved who cannot be contained in any place, not even in the whole universe, for he existed even before the universe was created. How, then, could he converse with anyone, or be seen by anyone, or appear in the smallest place of the world… Thus, neither Abraham, nor Isaac, nor Jacob, nor any other man saw the Father and ineffable Lord of all creatures and of Christ himself, but [they saw] him who, according to God’s will, is God the Son, and his angel because of his serving the Father’s will; him who, by his will, became man through a virgin, who also became fire when he talked to Moses from the bush.

Dialogue 127.1-4, Falls translation pp. 191-92 – see also Chapter 60.

In short, for Justin Jesus is a god who has in some sense become human, but his is not an incarnation of the god, God, but rather of a second and lesser god, the Logos. Justin seems to think it’s impossible, by reason of his transcendence, for God to become incarnate. Full divinity, he thinks, is incompatible with incarnation! Good thing God has this Logos to work through; he needs to work through another to, e.g. appear to Jacob. You might think that this is odd, that an omnipotent being should need to work indirectly with his creatures. Where’d he get such an idea? Directly or indirectly, he gets it from Plato’s famous dialogue Timaeus, as I discuss here.

All of this is not what a partisan of the Nicene creed expects or wants to find in Justin. Bird cites scholars asserting, implausibly, that surely Justin’s Logos is fully divine, as divine as the Father, but I think that’s the catholic narrative talking, not Justin. According to this false narrative, Christians always thought that the Son is fully divine, being uncreated and yet “eternally begotten,” the Second Person of the Trinity, the triune God, who becomes incarnate.

The work of Justin shows the falsity of these claims. Justin was well known and was at least somewhat influential in what was still a pretty small movement – more, I think, as time went on. (I think this Christian philosopher would have been pretty controversial in his own day.) But his Logos is neither the one God, nor a fully divine Person, nor one of three “Persons” in the one God. Like others in this period, he everywhere assumes that the one God just is the Father alone, which is to say that his theology was unitarian.

In the second and third centuries the only Christians who believed that Jesus is fully divine, that he’s the one true God incarnate, were the modalistic monarchians, those who like many today confuse together Jesus and God, as Origen observed.

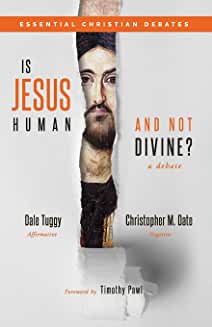

Why was this confusion rare? Because the New Testament assumes and asserts many simultaneous differences between Jesus and his God – see my debate book for these, and for a lot more on early subordinationist christologies.