What a great beard!

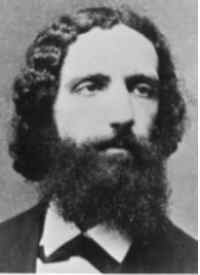

Franz Brentano (1838-1917), a forerunner of the phenomenological movement and the analytic movement, was of great influence on folk such as Edmund Husserl, Alexius Meinong, Anton Marty, Carl Stumpf, and Kasimir Twardowski. He is best known for his work Psychology From an Empirical Standpoint (1874). And in that work he is best known for his view that the mark of the mental is intentionality:

Every mental phenomenon is characterized by what the Scholastics of the Middle Ages called the intentional (or mental) inexistence of an object, and what we might call, though not wholly unambiguously, reference to a content, direction toward an object (which is not to be understood here as meaning a thing), or immanent objectivity. Every mental phenomenon includes something as object within itself… (Brentano, Psychology, 88)

So Brentano thinks all and only mental phenomena have intentionality, i.e. are directed toward an object.

Brentano was from a Catholic background, but defected, partly due to problems he had with the doctrine of the Trinity. Carl Stumpf, in his ‘Reminiscences of Franz Brentano’, writes about an incident in 1870:

[…] on 29 April, having come back from a vacation in Aschaffenburg, [Brentano] visited me and raised certain doubts about the dogmas of the Trinity and Incarnation which seemed insoluble to him despite all the usual distinctions between substance, subsistence, substitution, nature, person and hypostasis. […] Brentano’s motives [to defect from the Church] were of a theoretical nature, they were simply the result of internal contradictions in the Church’s doctrine which even his penetrating mind, after years of wrestling with the problem, could not resolve. For quite a while after his decision he did not tire of carefully re-examining the inferences which had brought it about, nor of trying every conceivable possibility for a way out. On 19 November he wrote to me in Göttingen of an enneakilemma, a nine-termed disjunction, in which he had summarised the contradictions in the dogma of the Trinity. (The Philosophy of Brentano, edited by Linda McAlister (London: Duckworth, 1976), pp.23-4, bold emphases added)

I don’t know whether the enneakilemma still exists. I would love to read it. Who knows what’s there? Perhaps it’s a killer objection. Or perhaps it’s rather like things I’ve already seen or come up with myself. Be that as it may, Brentano had an interesting account of substances and I hope to show next time how one can apply this to come up with an interesting account of the Trinity. So stay tuned!

Sounds cool!

Comments are closed.