Arius and Athanasius, part 1 — How is the Son produced? (JT)

This series is extracted from a paper I delivered at the APA in Chicago last month. I’ve basically just cut up the paper into smaller chunks.

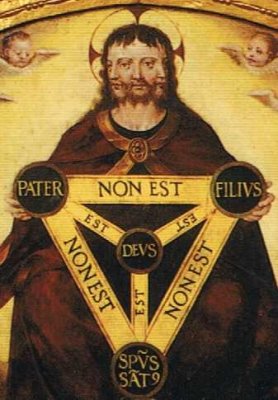

As we all know, the doctrine of the Trinity states that God is three persons: the Father, Son, and Spirit. Further, two of these persons, the Son and the Spirit, are produced. According to both East and West, the Son is produced by the Father, but the East holds that the Spirit is also produced by the Father, while the West holds that the Spirit is produced by the Father and Son together. But that’s by the by. The point is that some of the divine persons are produced.

The question that interests me is this: how, exactly, does one divine person produce another? In this series, I want to look at two 4th century attempts to explain how the Father produces the Son: that of Arius, and that of Athanasius.

Read More »Arius and Athanasius, part 1 — How is the Son produced? (JT)