This chart has been brought to you by the letter “R” and the number “4”.

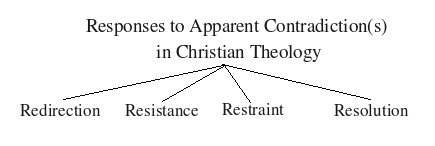

In this series I’ll describe 4 basic ways Christian thinkers respond to apparent contradictions in theology. I don’t claim these are complete. Maybe ya’ll can help me clarify and add to this scheme.

I’ve been working for a while on what I call “mysterianism”, and a main purpose of mine here is to locate this defense strategy and contrast it with others. (Mysterianism is a kind of Resistance.)

Above is my basic division. Future posts will give more detail, but here’s a brief illustration of each sort of response.

Objector/puzzled fellow believer/one’s intellectual conscience: “Huh? Isn’t X inconsistent?”

Responses:

- Redirection: Yeah, well, God is really wonderful, and X is true, important, and practical, and many other profound theological truths depend on X.

- Resistance: Yes, X is apparently inconsistent. Nonetheless, we may reasonably believe X.

- Restraint: X does appear to be inconsistent. But the doctrine in question, it needn’t be understood as saying X exactly… but I don’t know what to replace X with.

- Resolution: If the doctrine in question amounted to X, that doctrine would indeed be inconsistent. But on further examination, Christians needn’t commit to X.

Technorati Tags: 4 R’s, Redirection, Restraint, Resistance, Resolution, apparent contradicton, mystery, paradox, theological paradoxes, mysterianism

Pingback: trinities - Dealing with Apparent Contradictions: Part 11 - One last problem for Rational Reinterpretation (Dale)

I think if we are talking about strategies in the abstract it’s necessary to make the distinction, because when we are talk about apparent inconsistencies it makes a big difference to whom they are apparent. If X says that some set of claims held by Y is apparently consistent, it may well be that Y’s most reasonable general strategy is simply to ignore such an objection, or deny that there’s anything really underlying the objection. If John says something Mary holds is apparently inconsistent, it’s not always even going to be reasonable for Mary to go through the trouble of defending herself; the mere fact that something appears inconsistent to somebody is not really relevant to anything. (After all, there probably isn’t much that hasn’t appeared inconsistent to somebody.) It’s the type of appearance, not the mere fact, that requires a response.

But I agree that for ourselves it’s not a distinction with all that much practical use (except to remind ourselves to look further into things that seem inconsistent to us rather than just accepting them at face value); that’s because when we are looking into the matter for ourselves, we’re obviously going to be more interested in what appears inconsistent to us.

Fortuitously, this blog post gets at what I’ve been thinking about the mystery aspect of the faith:

http://fatherstephen.wordpress.com/2008/06/19/true-knowledge-of-god/

Pingback: trinities - Dealing with Apparent Contraditions: Part 2 - Redirection (Dale)

Carl,

I’m guessing even the most conservative Catholic will grant that there are (at least possible) limits to proper submission to the Church. Suppose you discovered there was something she taught which seemed as clearly contradictory to you as “There is a square circle.” But I agree with you that we ought to give some credit to those who have proceeded us in the faith, assuming they had something coherent in mind. You also have to keep this possibility in the back of your mind, though – that in fact they did not.

Brandon,

I think you’re right that people are often too quick to accuse great thinkers of inconsistency. There’s a human impulse to go for a “gotcha”… to catch people with their pants down, so to speak. But quite often, such accusations are based on misunderstanding. I find that my students often misread passages where a philosopher is discussing objections to his own views – and think that philosopher is (inconsistently) asserting those things. Of course, he’s in fact met said objections by making some distinction.

About your suggested distinction: I’m not sure how useful it is. I mean, suppose some doctrine appears to me to be contradictory. If that appearance stays after I look into it more, I’ll judge (tentatively) that it is. Often, I won’t have a view as to whether nearly any sane people would also view it is contradictory.

Perhaps what you’re getting at is this, though. Suppose I’ve concluded that doctrine D in contradictory. Then you come along and say it isn’t. As best I can tell, you’re sane and informed. So arguably, I now have a “defeater” for my belief that D is contradictory. (Or maybe I come to have a defeater after talking with you a bit, and deciding that yes, we’re talking about the same claims.)

I don’t think this is a bad impulse though. You should humbly submit yourself to the authority of the Church. Now, there does come a point where you should say, “Wait a minute, this is all crap, because blah,” but that point is pretty far out. To begin with, you have to assume that people knew what they were saying when they codified certain doctrines.

That said, I’ve been thinking about it recently, and Chalcedon only makes sense if you have a soteriology based around theosis/sanctification, and under a substitutionary atonement theory, it doesn’t really make any sense.

I think it’s useful to distinguish two very different ways in which something may be ‘apparently inconsistent’. If I claim that X is apparently inconsistent, I may mean that it looks to me (or you) like it’s inconsistent; but I may also mean the much stronger person that it would look inconsistent, at least prima facie, to virtually any reasonable person. In that second sense it’s possible to argue that person’s charge of apparent inconsistency is just not well-founded in the first place; that, in fact, the objector’s account of the ‘inconsistency’ doesn’t involve any apparent inconsistency on the part of the claim at all — there is nothing even to suggest any sort of contradiction — it’s an artifact of the objector’s own confusion. (One thing I’m constantly astonished with is in doing history of philosophy is how often even intelligent people slip into this. People will accuse Locke, for instance, of being inconsistency, and yet the argument they give would at best show that Locke is wrong, not inconsistent; or their argument for inconsistency turns out to be question-begging. Locke’s a good example, actually, because he often really is inconsistent, so when people claim that he is inconsistent on such-and-such, it sounds plausible just on the face of it, without regard for what Locke actually says. But sometimes it’s the objector who is confused and inconsistent, not Locke.) Presumably, though, this could be seen as a variation of either Resistance or Resolution.

Pingback: Mark Porter - Veni Creator Spiritus » Contradictions

Comments are closed.