A story about implicit faith…

A story about implicit faith…Once upon a time, there was a virtuous and patriotic Russian peasant named Georgy. Georgy lived a simple life among simple people, in a village so far out in the boondocks of the USSR that World War II – what Russians call the Great Patriotic War – passed by practically unnoticed. The farming life had treated Georgy and his family well, and he had only good thoughts towards the great leader of his country, Comrade Stalin.

After a particularly vicious and thorough purge, Stalin’s government found itself in need of new secret police agents. Being vigorous, patriotic, single, and malleable, one of Stalin’s recruiters focused on Georgy. (He overlooked Georgy’s moral goodness.) Hearing about this exciting and rewarding career, Georgy was strongly inclined to make the deal.

Georgy’s friend Artem, however, was more cautious. “Georgy – are you sure this is a good idea? I mean, you’ll be expected to do,say and believe a lot of things you haven’t yet imagined.”

“Sure – well, that’s the excitement of it. What’s there to worry about? I love the Motherland. So does Uncle Joe.”

“Well, Georgy, are you a communist?”

“What’s that?”

After a stunned silence, Artem continued. “Georgy, do you believe in the collective ownership of the means of production?”

“If Uncle Joe is in favor of that, then so am I. I’m quite into collecting myself. Stamps, for instance.”

“Georgy, that’s a very, um, loyal and patriotic attitude, but how can you be sure that when you find out all of Comrade Stalin’s policies, you’ll agree with them, or at least be willing to carry them out? I mean, saying that you’ll do this when you find out about them is one thing, wanting that to happen is another, but really being inclined that way is another. How do you know you actually are inclined that way, my friend?”

“My dear Artem, I have implicit faith in Uncle Joe, and in all he stands for. I believe whatever he does.”

“But how do you know that you won’t disagree, or just not agree, when you find out in detail what our Comrade Leader believes?”

“I just do. I just love Uncle that much.”

“What if he tells you that the sky is green?”

“He wouldn’t do that.”

“But if he did, Georgy, would you believe him?”

“No.”

“But for all you know, he believes it, Georgy. If so, you don’t believe everything Uncle Joe does, though you say you do, and you wish you did.”

“That’s exactly what I do wish. I’m going to sign up now.” And he did.

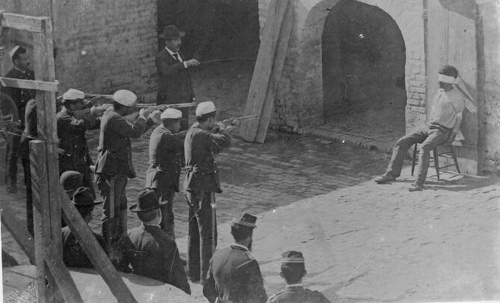

Being as morally upright as he was uninformed, Georgy’s career in Stalin’s secret police was brief, although he went out “with a bang”.

Hi Ryan,

Short answer: yes.

Long answer: In my initial posts, I said having (only) implicit belief in a claim X isn’t a way of believing X, because one needn’t grasp any of the content of X at all. e.g. I “believe”whatever Einstein does about physics. As Brandon pointed out, a belief is best thought of as a tendency to think in a certain way. Well, maybe I do have this tendency with respect to Einstein – because (just imagine) I’m a brilliant youngster who actually would be inclined to agree with Einstein, were he or someone else to instruct me. So may I DO have a tendency to believe X, but it’s a higher-order power – the ability to get the ability to think the world is the way X says. Now I threw in a complication with my Stalin post: maybe I’m a brilliant, physics-capable youngster but I’m not so inclined that I would agree with Einstein in exposed to the relevant evidence, etc. Maybe I’d disagree with some of it, or maybe it is now indeterminate what I would do – I could make choices so that I’d go either way. As some Catholic thinkers noted in another post – the notion of having an implicit belief in X is very vague – it’s not clear really what state of mind that is, not clear quite how the implicit believer needs to be related to X. My main concern about implicit belief in a doctrine X is that theologians talk about doctrine X like it’s a really important bit of information, which will serve as a guide to other beliefs, to action, to devotion, to social action, etc. It’s not clear that a merely implicit belief in, say, the Trinity can play those roles.

People also talk about having “implicit faith” not in a doctrine (or bunch of them) but in an institution – really, in the people past and present who have run it. The Catholic Church has in no uncertain terms demanded a kind of unquestioning trust in whatever they say – see the statement of the first Vatican Council of 1870. To me, it isn’t rational to adopt that stance with respect to them, to have “implicit faith” in them, in that I’ll commit to whatever they should say. Their track record in doctrine and in general holiness are the main issues to me. But again, even if one says and fully intends to believe whatever Mother Church says, whether or not you are really committed to what she says depends on what tendencies you actually have. This can only be know, I guess, in retrospect, i.e. I find out she says Y, and even find out her main reasons for Y, and yet, I don’t believe Y. Then, my implicit faith in Y was an illusion – perhaps even a bit of self-deception.

To continue:

For the sake of discussion, let’s suppose that “Catholicism is pretty off track.” Also, let’s suppose, as you said, that “the apostles’ trust in Christ was wholly reasonable.” And finally, let’s suppose, as I said, that this trust can be described as “believing in a person (Jesus Christ) prior to being fully aware of what that belief entails.” Given all that, then the problem with “Catholic implicit faith” is just the “Catholic” part, not the “implicit faith” part, right? And, wouldn’t implicit faith be OK as long as it is justified by the right evidence and pointed towards the right target?

Hi Dale, my intention here isn’t to dissuade you from your reading of the NT and of church history. (Sure, there’s a time and a place for apologetics and the Catholic versus Protestant thing, but your blog succeeds in part because of its tight focus, and I wouldn’t want to diminish that.)

Sincerely, my intention here is to learn as much as I can about the Trinity from you and the other contributors and commentors. I hope it’s no cliche to say that “dealing with apparent contradictions” in the Trinity has kept me up at night – for me, this is all more of an existential quest than a Rubik’s cube. I’ve been looking for guides and I’ve been grateful to find your blog. I appreciate the pursuit of precision and the collective philosophical training and talent found here.

I’ve got to head out to the wake of my wife’s distant relative. I’ve got a few more scattered thoughts about implicit faith to come.

Hi Ryan,

My view is that trusting in Christ & the apostles, and trusting in the Catholic church are two different things. If you think that trusting the Church is the means of trusting Christ, then God bless you in your journey. I guess I’m one of countless people whose reading of the NT (and of church history) has convinced my that Catholicism is pretty off track.

Thanks for your response Dale. Now I don’t understand why the implicit faith defended by Aquinas is more like “Georgy and Stalin” rather than the Apostles and Christ? Wouldn’t a good Catholic (I aspire to be one) say “I have ample evidence for the Church’s trustworthiness in her miracles, the content of her teachings, and her holiness”?

Hi Ryan,

You’re welcome. There’s more coming too – I’m really working up to the topic of what I call Mysterian Resistance.

My view is that the apostles’ trust in Christ was wholly reasonable. They couldn’t be 100% certain that Jesus wouldn’t turn out to be bad or untrustworthy at some future date, but they had ample evidence for his trustworthiness in his miracles (amounting to an endorsement by God), the content of his teachings, and his holiness. So I think that makes their case quite different from that of Georgy and Stalin.

Thank you for your series on dealing with apparent contradictions, I have enjoyed reading and pondering. Today, I’ve been thinking about Peter’s response in John 6: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We believe and know that you are the Holy One of God.” I’m wondering if it has some similarities to Georgy’s implicit faith in Stalin – believing in a person prior to being fully aware of what that belief entails… So, how would you categorize the relationship of faith and reason in the responses of the Apostles to Jesus Christ in the Gospel?

Carl, I thought someone might take my story the wrong way. I almost added this note: I’m not comparing anyone to Stalin here. I chose him, because of his contrast with the very good Georgy. So happily, I’ve avoided Godwin’s Law entirely. 🙂

Nor is the point, really, to blame Georgy. To get the point of this story, you must connect it to comment #14 here.

Comparing your opponents to the supporters of Stalin doesn’t quite invoke Godwin’s law, but really only on a technicality.

If anything doesn’t this undermine your position, since we would say that even a good person is somewhat (but not fully) responsible for their choice to support a morally reprehensible regime even if they aren’t aware of the regime’s true nature if it turns out that they could have relatively easily learned more about it? That is, we have a moral responsibility to be become more aware of certain facts about society (but not all facts, obviously). Therefore, ignorance is not a blanket excuse. On the other hand, if Stalin had been really good at hiding his crimes, then his servants wouldn’t have been considered accomplices to his crimes.

Pingback: trinities - Dealing with Apparent Contradictions: Part 5 - Aquinas on Implicit Faith (Dale)

Comments are closed.