I have been telling the Maverick Philosopher here about Benjamin Sommer’s theory of divine fluidity, which is one solution to the problem of anthropomorphic language in the Hebrew Bible. The problem is not just Genesis 1:26 (‘Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’) but also Genesis 3:8 ‘They heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze’. Can God be a man with feet who walks around the garden leaving footprints? As opposed to being a pure spirit? The anthropomorphic conception is, in Maverick’s opinion ‘a hopeless reading of Genesis’, and makes it out to be garbage. ‘You can’t possibly believe that God has feet’.

I have been telling the Maverick Philosopher here about Benjamin Sommer’s theory of divine fluidity, which is one solution to the problem of anthropomorphic language in the Hebrew Bible. The problem is not just Genesis 1:26 (‘Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’) but also Genesis 3:8 ‘They heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze’. Can God be a man with feet who walks around the garden leaving footprints? As opposed to being a pure spirit? The anthropomorphic conception is, in Maverick’s opinion ‘a hopeless reading of Genesis’, and makes it out to be garbage. ‘You can’t possibly believe that God has feet’.

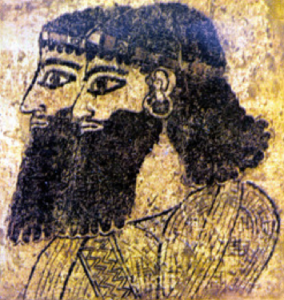

Yet Benjamin Sommer, Professor of Bible and Ancient Semitic Languages at the Jewish Theological Seminary, proposes such a literal and anthropomorphic interpretation. As he argues (The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel), if the authors of the Hebrew Bible had intended their anthropomorphic language to be understood figuratively, why did they not say so? The Bible contains a wide variety of texts in different genres, but there is no hint of this, the closest being the statement of Deuteronomy 4.15 that the people did not see any form when the Ten Commandments were revealed at Sinai. ‘Until Saadiah [the 10th century father of Jewish philosophy], all Jewish thinkers, biblical and post-biblical, agreed that God, like anything real in the universe, has a body’. A proper understanding of the Hebrew Bible requires not only that God has a body, but that God has many bodies ‘located in sundry places in the world that God created’. These bodies are not angels or messengers. He says in this this interview that an angel in one sense is not sent by God but actually is God, just not all of God.

[It] is a smaller, more approachable, more user-friendly aspect of the cosmic deity who is Hashem. That idea is very similar to what the term avatara conveys in Sanskrit. So in this respect, we can see a significant overlap between Hindu theology and one biblical theology.

Do hard-assed logicians such as ourselves balk at such partial identity? Not necessarily. I point to a shadow at the bottom of the door, saying ‘that is the Fuller Brush man’. Am I saying that the Fuller Brush man is a shadow? Certainly not! Nor, when I point to a beach on the island, saying ‘that island is uninhabited’, am I implying that the whole island is a beach. By the same token, when I point to the avatar, and truly say ‘that is God’, am I implying that God is identical with the avatar? Not at all. Nor am I saying that God has feet, even though the avatar has feet. The point is that the reference of ‘that’ is not the physical manifestation before me, but God himself. Scholastic objections that we cannot think of God as ‘this essence’ (ut haec essentia) notwithstanding.

A somewhat similar approach was suggested by Richard Cartwright in his famous essay ‘On the Logical Problems of the Trinity’. We can say ‘that is Descartes’ (pointing to a picture), ‘that is the Sonesta Hotel’ (pointing to a reflection in the water), or ‘that is the Fuller Brush man’ (pointing to a foot in the doorway).

Each of these suggests a possible construal of our Trinitarian sentences, and a full treatment would take account of them all. But perhaps I have said enough to convince you of the difficulty of the subject; and, if I have not exhibited the rewards of truth, I hope I have demonstrated the dangers of error.

Sommer’s approach is perfectly consistent with this.

Sommer insists that core Christian assertions—the trinity and incarnation—are not theologically impermissible within the world of Judaism, but rather are faithful to the fluidity model of divinity found in ancient Israel. For modern Jews, Sommer demonstrates how biblical notions of fluidity and antifluidity pose challenges for both liberal and conservative Jews, though not in the same way. He concludes by insisting that, contrary to customary positions, it is the fluidity model that offers the strongest statement of monotheism consistent with the personhood of God.

Interesting, although I’m not at all sure “faithful” is the best term with respect to the Trinity developments into the Greek and Latin milieu – maybe we could claim that it is in line with that.

I’d love to hear any recommendations for reading on the subject of anthropomorphic usage. I recently stumbled over the fascinating Psalm 11:5 that asserts that God has a soul (that hates the wicked) and that the people of Israel also have a heart and a soul (see Psalm 33:20-21).

There is also a question raised here for me of translation fidelity (culturally and textually, note the LXX high reluctance to translate Yahweh as being a rock for instance). Note also how a lack of polytheistic practice could be considered as *atheism*, at least in the fourth century (and I am sure before).

Thanks for the stimulating post.

Comments are closed.