|

Listen to this post:

|

Dr. Ryan Mullins, currently in a post-doc at the University of Helsinki in Finland, is doing some of the best work today in analytic theology, especially on topics like God and time, so-called “classical” theism, and God and emotions. A frequent guest on theologically-oriented YouTube channels, I’ve seen a number of his interviews, and they never disappoint. Also, you must check out his excellent podcast The Reluctant Theologian.

In “Is Divine Simplicity Compatible with Trinitarianism? | Dr. Rob Koons & Dr. Ryan Mullins” from August 2020, Dr. Mullins is called upon to interact with the difficult new Trinity theory of Dr. Koons. And Dr. Mullins nicely, with his typical clarity and charity, brings out some hard problems for that theory.

But in this post the part I wanted to comment on some of Dr. Mullins’s starting-points in the conversation. Starting at 11:41, he summarizes what “the Trinity” teaching is, as in, what are the fundamental claims which are included in catholic trinitarian traditions, specifically the 381 “Nicene” creed. He gives us five claims, which I’ll give mostly in his words and then comment on.

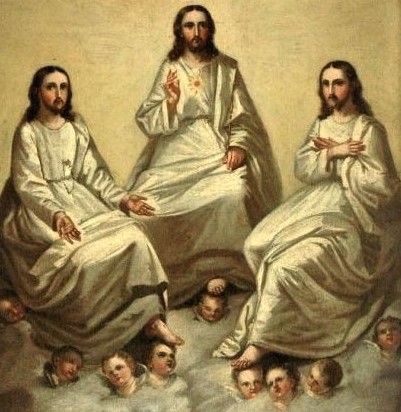

T1: There are three divine Persons.

Comment: Dr. Mullins goes on to make clear that he understands these “Persons” to be what I call selves. I agree that the New Testament clearly assumes and implies that the Father (aka “God”) is a self and that the Son (aka “Jesus”) is a self, and that they are not the same self. (This is clear because the New Testament portrays them as being in a unique interpersonal relationship.) It is far from clear, looking at New Testament language and teaching, that “the Holy Spirit” is supposed to be a self distinct from both Father and Son. See here for why.

What is meant by saying that each of these selves is divine? I think it’s somewhat clarified by Dr. Mullins’s third point below.

T2: The divine Persons are not numerically identical to each other.

Again, the case of the Father and Son, this could hardly be more clear, because according to the New Testament writings, they simultaneously differ in a number of ways, and not only relationally but intrinsically. And it’s self-evident that things which intrinsically differ are numerically distinct, i.e. not one and the same thing. (Basically – a thing can’t be and not be a certain way at a certain time.)

It is much less clear that “the Spirit” is supposed to be something distinct from God and from the Son of God. In fact, some uses of spirit-talk in the Bible arguably seem to be references to God (aka “the Father”) and a few even seem to be about the Son!

T3: The divine Persons share the divine essence (i.e. are homoousion).

This is the “signature” claim of the ancient “pro-Nicene” catholics and has been the rallying cry of catholic theologians of all stripes since it was enshrined into orthodoxy by the 381 council, obediently following the pro-Nicene emperor who’d decided, mid-controversy, that the time for arguments was over.

What is “the divine essence”? In ancient Greek philosophical traditions, this was understood to be what philosophers now would call a kind-essence. It’s akin to human nature, or the essence “humanity” – that is, whatever property or properties it is in virtue of which their owner is a human being. That is, the human essence would be that which makes any human a human. Similarly, “the divine essence” is supposed to be that property or properties because of which their owner is a god.

Now, the way Dr. Mullins has formulated T3, one might think that it is only the Persons together, or the Persons as constituting the whole which collectively have the divine essence. But I think T3 is equivalent to: the Father has the divine essence, the Son has the divine essence, and the Spirit has the divine essence. It’s not only the collective or whole that has the divine essence, but each Person does. (If ask to be corrected if I’m wrong here.)

That is, three different (numerically distinct – see T2) intelligent beings (selves, “Persons”) have the divine essence. But then, each one has exactly what it takes to be a god. Each having the divine essence, the Father is a god, the Son is a god, and the Spirit is a god. But are they the same god? No, they can’t be. For some x and some y to be the same F means that x is an F, y is an F, and that x=y (i.e. x just is y, x and y and numerically the same thing). But these three (see T2) are not the same thing. So, no pair of them can be the same god. This looks like three gods – which is an objection as old as the time of St. Basil, in my view slightly before catholic tradition turned trinitarian.

T4: The divine Persons are related in such a way as that there is only one god, not three gods. (monotheism)

Comment: this is not at all a definition of “monotheism.“ Monotheism is the claim that there is exactly one god. (What’s a “god” you say? I explain more here.) But I think Dr. Mullins means to say that the relations between the three are somehow the monotheism-preserving component of trinitarianism.

But it’s a murky claim! If each Person is divine, that seems to entail that each is a god. (This is what leads Dr. William Lane Craig to buck tradition and say in effect that none of these selves is divine, but only the Trinity!) Once we’ve gone this far – saying that each Person has by himself all that it takes to be a god, what relation between them can we now point to that would reduce the number of gods in the theory to one?

Indeed, there’s an excellent recent paper pressing this issue for “social” trinitarians; it’s one of the better recent papers I reviewed when updating my “Trinity” entry last year.

What is this monotheism-saving relation? Well, some collapse together the Persons into one and the same thing, that is, urge that the three are really numerically one, despite appearances. But this should be rejected for the reason discussed above. Again, some, like Basil in some moods, suppose that it is precisely essence-sharing which makes the Persons amount to one god. But if “the divine essence” is supposed to be a property which is in principle had by more than one thing, then it would not guarantee that the there are one god. And if “the divine essence” is supposed instead to be an individual property, a feature such that in principle there could not be two things that have it, that would indeed entail that the Persons are the same god, but at the cost of entailing also that they are one and the same (i.e. numerically identical) – in short, Person-collapse.

Others have speculated that maybe “perichoresis” is what’s needed. Or maybe it’s the Persons being “constituted by” the same stuff. Others have supposed that the cooperation, or the necessary cooperation (the impossibility of their not cooperating) implies that they’re the same god. Others demote the Persons from each being individually God, urging that each is instead a god-part, each a proper part of the Trinity which is the one God. Others imagine that it’s just the eternal “processions” which make them the same god.

The problems with all such suggestions generally are that (1) they are not clearly taught in Scripture, and (2) it seems on reflection that multiple gods, were such to be possible, could stand in that relation to one another.

But it’s worse that this. T4 is so vague that it doesn’t even require that there is exactly one sort of relation that implies that among these three Persons there is only one God. For all that’s been said, there might be a couple of relevant relations. And in fact, T4 leaves the door open to a kind of unitarian theology! Here’s how.

Suppose that the famous subordinationist unitarian Dr. Samuel Clarke is right. There here is how the Father is related to the one god: numerical (absolute) identity. This is not so with the other “Persons.” Per T5 below, the Father eternally causes the Son and the Spirit, and shares as much divinity with them as in principle can be shared. Of course, aseity can’t be given to or caused in another! So only God, aka “the Father,” exists a se. But Clarke thinks he can give the other divine attributes to the Son and Spirit. So, being related in these ways, there is only one god. (Of course, there are two other nearly divine beings…)

Further, I don’t think it is a required part of trinitarian tradition that somehow the relations between the Persons ensure monotheism. Here’s a very simple way to ensure monotheism: identify the one god with the Trinity. For any trinitarian theology, there’s only one Trinity (Keith Ward’s speculations are the exception that prove the rule), so identifying the one god only with the one and only Trinity ensures that there is one and only one god. This, in my view, is the place that Basil’s problems drove his younger associates the Gregorys to. Basil’s many flailing answers to tritheism objections that were constantly lodged by non-Nicene catholics didn’t satisfy, so the Gregories came up with the strategy of saying that actually it’s the whole Trinity which is the one God, not the Father alone.

This, I claim, is a definitional and foundational claim to any truly trinitarian theology, and it is precisely where trinitarian speculations clash with clear biblical doctrine.

Of course, there is still a problem for the trinitarian here. It’s not enough to have a self-consistent monotheism to identify the one God with the Trinity if one also posits three divine beings (the “Persons” of the Trinity).

In sum, it seems like a very pressing problem for Dr. Mullins, and for any trinitarian who conceives of the “Persons” as distinct selves, each of which has the divine essence.

T5: The divine Persons are distinguished from one another and related to one another by causal relations, namely that the Father eternally causes the Son to exist, and the Father (or: the Father and the Son) cause the Spirit to exist. (the doctrine of divine “processions”)

As Dr. Mullins points out, T5 is rejected by many Protestant theologians today, including him and Dr. Craig, because it is not taught in the Bible and because it entails that the Son is less divine than the Father (because full divinity requires aseity, and given T5 only the Father will have that divine perfection). And this is not only a 20th c. stance; in fact, a leading 19th c. trinitarian evangelical Bible scholar famously took this stance about “processions.”

In conclusion, Dr. Mullins has come much closer to capturing the essence of “the Trinity” than is often done with the rather over-compressed B.B.-Warfield-type summary, as I discuss here. Even so, the vagueness of his T3, T4, and T5 make clear that “the Trinity” is not some one theology, a single account of God, but is rather some vague ideas which Christian have since their inception been pretty much on their own to try to make sense of (though most really don’t try).

But Dr. Mullins has left out what I think is really the key claim of any truly “trinitarian” theology, that g = t (God just is the Trinity, i.e. the only god is none other than the triune god). Instead of this, he’s substituted a vague claim (T4) which is something which is understandably on the “social” trinitarian agenda.

But suppose we consider three girls. Could they be so related that they are the same girl? It seems that short of destroying them and constructing a single girl out of their remains, they could not be the same girl. But three divine beings (three things with the divine essence) is by definition three gods, and so it’s hard to see how they could be related to one another so as to be the same god. Would more would it take to please a tritheist than a theology on which there are three divine beings?

Finally, Dr. Mullins is right that T5 has been enshrined as a required part of catholic trinitarian traditions. He’s not, then, as a denier of T5, a fully orthodox trinitarian. I, for one, don’t think that’s a bad thing! But the questions for a Protestant should be: (1) how many of T1-T4 (and the key trinitarian claim that g=t) are really taught in Scripture, and (2) are there any clear Scripture-teachings which contradict any of T1-T4?

I humbly suggest that Dr. Mullins should devote some of his research agenda to these important biblical questions.