|

Listen to this post:

|

In her interesting essay “For the Love of Reason” (in this book) philosopher Dr. Louise Antony describes her youth as a very serious and committed Roman Catholic, and how she eventually became an atheist in college. It seems that baffling Trinity claims did play a role in her ongoing frustration, although it was considerations about God and evil that finally moved her in the direction of atheism. She writes, about her questions on puzzling topics such as the Catholic doctrine of Limbo,

Not many adults were willing to go on to round three. They would grow impatient. “Louise,” my mother would say, “you just think too much.” Sometimes they’d get positively angry. What was the matter with me? Why did I have to argue about everything? Didn’t I realize that some things just had to be taken on faith? In general, I was informed, I should concentrate more on loving my neighbor and less on being a smarty-pants.

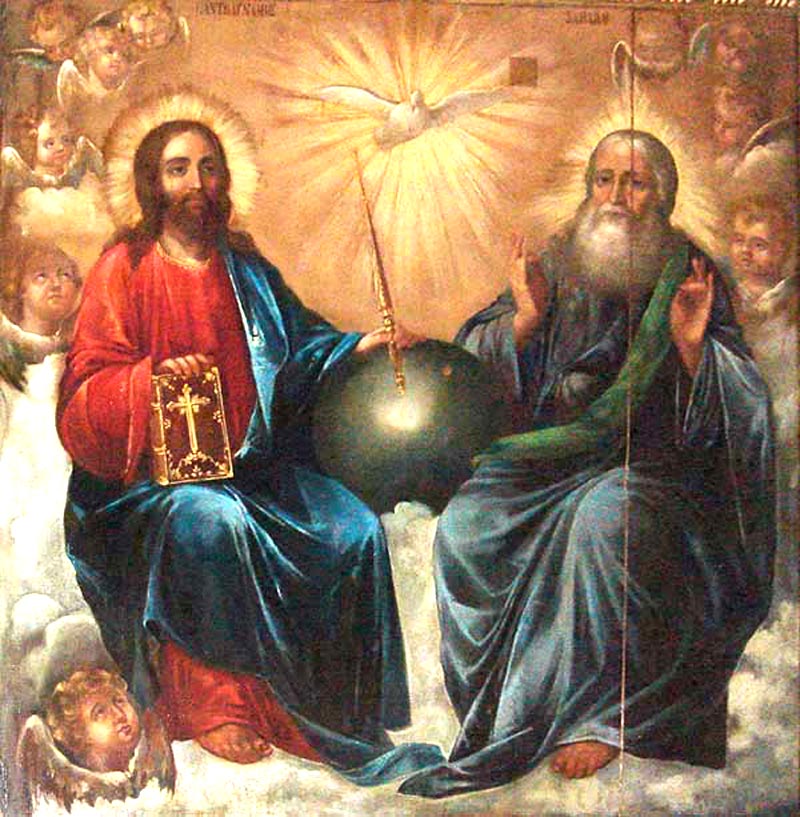

None of the nuns or priests from whom I received religious instruction were of any help on the matter of Limbo, nor, for that matter, on any of the other issues that troubled me. There was also the Trinity: how could there be “three persons in one God”? I remember trying to wrap my childish head around this “holy mystery” in the classes preparatory to my receiving my First Communion. For several months running, I would go home from religious education one week, think hard about the whole thing, then return the next week with a new idea to offer Sister. It was always wrong. Maybe God was like a family, I suggested. There was, after all, a Father, a Son, and (remember, now, I was only six-and-a-half, and He was usually depicted as a bird) the family pet, Holy Ghost. No, said Sister, God is not like a family. OK—maybe God is like a three-leafed clover (I had just been taught that this was how St. Patrick explained the Trinity to the heathen Celts in Ireland)—the Father is one leaf, the Son is another, the Holy Ghost is a third, and they’re all parts of God. No, said Sister, God is not like a three-leafed clover, St. Patrick notwithstanding. Well, maybe each person is like a different mood of God—God the Father is the angry mood, God the Son is the loving mood, and the Holy Ghost is some other kind of mood. No, said Sister, not moods, either. Finally Sister, clearly exhausted, told me that I’d never understand the Trinity because it was a mystery of faith. Mysteries of faith are, by their nature, incomprehensible. We must simply believe them. But how can I believe something I don’t understand, I asked? “Just memorize your Catechism,” was Sister’s reply. “Belief will come.”

(pp. 42-43)

Dr. Antony immediately goes on to describe her troubles with another fiction: Santa Claus! (pp. 43-44) Then she reflects on the overall impact of these conversations on her.

What I got from all of this was that thinking was fine and good, but only in its place. A little learning might be a dangerous thing, but a lot of thinking was worse. . . .I still, to this day, resent the way I was made to feel as a child—that my questioning was inherently bad, that there was something wrong with me for wanting things to make sense.

As I’ve said, the reactions of grownups to my questions about religion were doubly distressing to me because of their dissonance with the principles adults were explicitly promoting in other contexts. In school, a broadly libertarian and individualistic ethos prevailed. We were always being exhorted to “think for ourselves.”

. . .Somewhere along the line, I came to the conclusion that my inquisitiveness was sinful. It was not just that it was prideful—I’d been told that explicitly, and often enough. This new idea was that the questions had been put into my by the devil, and that, indeed, the whole world had been mined with dangerous ideas, ideas that could threaten my faith if I indulged them. No one told me such a thing in so many words, but it seemed to me a good explanation for the taboo against thinking in religion, together with apparent inability to respect it.

My little theory kept me in a pretty constant state of anxiety, lest I take seriously something that turned out to be incompatible with religious teachings.

(pp. 44-45)

There is a real cost to dodgy speculations about God! What is a fun plaything for intellectuals can be a source of painful confusion for an earnest kid or just, an ordinary adult in the pew. Catholic trinitarian traditions are what conditioned people so that they would mistreat this very smart and curious little girl, and they were part of what led her to hate her own gifts in a way that was not going to work, long-term. She, caring about truth, was not going to be content with parroting formulas she doesn’t understand.

Dr. Antony is aware that some decide that staying with a religion is worth basically going along with, or even pretending to believe, things which they do not believe (p. 56) She just wasn’t willing to do it.

I suggest that a Christianity which is free of theories like the Trinity and Limbo may do a better job, in general, of keeping people like Dr. Antony. At least, it can if it also puts aside unbiblical yet traditional misology (hatred of reason). This is at least as big a tradition in many streams of Protestantism – just read Calvin and Luther. About this, next time you read Proverbs, which is largely about the importance of wisdom and knowledge, try to find the part where it dumps on “human reason” as a crummy, ruined, or overall troublesome and dangerous thing.