Many of you know that I’ve argued in several ways, in print, against “social” Trinity theories, and particularly the sort which holds that Father, Son, and Spirit are a group/community/quasi-family.

Many of you know that I’ve argued in several ways, in print, against “social” Trinity theories, and particularly the sort which holds that Father, Son, and Spirit are a group/community/quasi-family.

On such theories, it turns out that the one “God” is a group – a group of equally divine selves (aka gods – though they don’t like that term in the plural). This is surprising to be sure – is not the God of the Bible a super-duper self? One who is all-knowing, who loves and hates, carries out plans of action, smites and heals? Moreover, theism is usually explained as belief in one perfect, non-physical self, creator off all else.

Social trinitarians have of late been pushing back. “God isn’t one person, he’s three! We Christians have never said – or at least, never should have said – that God is a person. He’s not a person, though he’s personal. And that makes our view monotheistic.”

(A similar dialectic occurs with “social” theorists who don’t say that Father, Son, and Spirit are a mere group. Instead, they constitute or are within some one thing – but this thing is not a self.)

Now I think this response is wrongheaded in several ways, and am working on at least one paper responding to it.

But for now I note that a number of these “social” theorists are evangelicals, and thus many of them tend to take positions in other areas which push in the opposite direction.

- Christology. Who is Christ? God. And Christ is a self – one with two natures. Thus, God is a self as well – the same one as Christ.

- Theistic piety or spirituality. God is a he, not an it. He’s someone you can talk to, someone who loves you, someone who sympathizes with the downtrodden. He’s far from being an it – a force, “being itself”, or the other high-falutin’, abstract things people have imagined. Which brings us to:

- “Worldview” apologetics. Eastern (Buddhist, Hindu) views of ultimate reality are often criticized for their “impersonal” take on the ultimate. Theism – seemingly belief in a perfect, provident self – is argued to be more reasonable, and perhaps more practical as well.

In this series, we’re going to have fun with video – with interviews with some philosophical theologians, Christian and otherwise. Each time I’ll like an interview clip, and comment on the guy’s answers.

These are from the TV series Closer to the Truth, which I believe airs on some American PBS stations. The interviewer has a pretty impressive resume. He asks each interviewee: “Is God a person?”

The question, I take it, is not whether or not God is a human being – but rather, is God a self – a subject of consciousness, what Descartes calls a thinking thing, something with will and intellect.

This is my “local definition” of person

“A person is a self-conscious entity, endowed with reason, freedom and will”

Note #1: there is a substantial philosophical reason for NOT using the more familiar expression “free will”, and for distinguishing between freedom and will.

Note #2: I still prefer the term “person” to “self”, because, while person may, for those who know of ancient Greek and philosophy, carry the (modalistic, merely phenomenal) idea of prosopon, mask etc., OTOH the term self does NOT entail at all self-consciousness.

Hi Andrew,

Yeah, I’m saying that a “notional act” is a unique activity performed by one or two divine persons but not three. That’s how, say, Scotus or Ockham take it.

JT Paasch wrote:

“the mental lives of the persons are constituted by shared mental activities (the so-called ‘essential acts’) and unique mental activities (the so-called ‘notional acts’).

So I think it’s rather traditional and apt to say, as you have, that the persons share certain mental activities but not others.”

This is intriguing, JT. I would have thought a typical conception of notionality dictated merely different “modes of possession” (of the one essence/will/thought etc.). Are you saying something more?

Gents – sorry I’ve been MIA. Been swamped in writing and now the new semester.

A few comments.

“God is a person.”

Does this imply that God is one person (Fortigurn) or does it leave open that he’s three (Scott)?

I think it depends on the meaning of “person”. If it is a role or character or something (first entry in the OED) then Scott is right. Just because God is one of those, it doesn’t rule out that he’s also seventeen more.

On the other hand, if a person is a self, roughly a thinking thing, then I take it the above statement would imply that there’s some self to which God is identical. This would limit the number of “persons” God could possibly be to one.

Compare: “Fido is a dog.” “John is a human being.”

Thus, “One person is three persons” needn’t be a contradiction. It may be true, if it means “One self plays three roles” or something like that.

On legal persons – Brandon, thanks for that Hobbes reference – Hobbes is a real can of worms on this topic!

It so happens that I’ve been working on some papers on ST theories which deny that God is a self. Might God/the Trinity still be a “legal person”? I suppose. But note that legal persons exist only relative to laws. And most of us, including me, assume that such are mere “as if” persons. When we, or some judge etc. thinks of a corporation such as BP as a self with knowledge, rights, actions, and so on, this is simply because practically, it is convenient to deal with them this way. We don’t find this at all confusing – we all understand that a mere ‘legal person’ isn’t a self – because we’re not inclined to suppose that a thing like BP is literally a self. Interestingly, the case is different when it comes to God. Most Christians can’t long escape the gravity of the people, with its many vivid portrayals of God as a self. So even folks with highly sophisticated Trinity theories on which “God” is not itself a self find themselves thinking and speaking as if it were. So, for example, God is never referred to as “it” by STers.

Oops, that last paragraph there was supposed to be deleted. It just repeats the earlier one.

I don’t think that simplifies it at all.

I happen to think that the traditional Latin scholastic view of the trinity sees the mental lives of the persons as being constituted in an analogous way to the being of the persons. That is, the persons are constituted by a shared constituent (the divine essence) and unique constituents (the so-called personal properties), and likewise, the mental lives of the persons are constituted by shared mental activities (the so-called ‘essential acts’) and unique mental activities (the so-called ‘notional acts’).

So I think it’s rather traditional and apt to say, as you have, that the persons share certain mental activities but not others.

I myself think the persons share some of their mental activities, and those shared activities constitute their ‘shared mental life’. In addition, though, a particular divine person might also have their own mental activities, and so those unique activities (plus their shared mental activities) would constitute the mental life of that one person.

JT Paasch,

Thank you for clarifying that while I try to think these things through. I suppose that each person of the trinity has his own mental acts while each is omniscient and likewise each completely understands each others mental acts. Also, there could be sharing of their thoughts due to their indivisible oneness. And I assume this oversimplifies the thoughts of the persons of God.

Hi James,

That’s a wonderful question, and in light of it, I should rephrase my statement that you quoted. Earlier, Scott seemed to suggest that since I said the persons have distinct mental powers, I must think they have distinct mental acts too. I was denying that with the comment you quoted.

But I didn’t mean to suggest that the persons have no distinct mental acts. I was only trying to say that the persons could share some of their mental activities even if they have distinct mental powers — but I say ‘some’ rather than ‘all’ because I want to leave room for the possibility that a person performs unique mental activities as well.

So on my view, Christ could still have his own thoughts (such as those he had on the cross) — though of course those unique thoughts would not be part of the persons’ shared mental life, they would just be part of Christ’s mental life.

@Fortigurn: I am not in any way denying that trinitarians believe in three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

There does not seem to be any problem in asserting that “God is a person” can refer to this person (Father), or to that person (Son), or to this person (Holy Spirit). The “or’s” could be taken in the divided sense or the composite sense, and it seems that most trinitarians would take them in the composite sense, which leads to your actual worry.

So, the debate is not about the statement, “God is a person”, but about the statement “God is three persons.” But the latter statement is not what we, or at least I, thought we were talking about.

I’m not certain that there is a consensus among trinitarians, at least, persons who have a Phd. in theology or philosophy and are trinitarians, about whether and how to understand the statement “God is three persons.” The first question to ask would be, what does the term “God” refer to in this statement? It wouldn’t refer to a person, because then you’d get “A person is three persons”. I don’t think any trinitarian would accept this, let alone anyone else.

I think different trinitarians would understand this statement differently depending on their metaphysical account of the trinity of persons, and whether they are in the family of “social trinitarians” (ST) or non-social triniatarians (Brian Leftow’s LT).

Hence, the statement “God is three persons” could be understood in diverse ways by different trinitarians depending on their motivations and what not. Some might interpret it like this: “Deity (the divine essence) is essentially numerically the same thing as, without being identical to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit”. This isn’t the only way to interpret the statement “God is three persons.” So, your worry about the statement “God is three persons” is not settled by trinitarians; so even if you’ve achieved a “gotcha” moment with one trinitarian, you might not with many others.

Scott,

That was never in dispute. What was in dispute was whether the indefinite article is indefinite in number. It isn’t. If you say ‘God is a person’, then you are saying God is one person, not three.

The problem is that it’s satisfied by all of them. That’s precisely why these qualifying terms were invented in the first place, to make the distinction between persons which the Bible never does. God the Father is a person. God the son is a person. God the Holy Spirit is a person. But God is three persons.

Believe it or not, you still end up with three persons. If you want to avoid ending up with three persons, then you need to stop being a trinitarian. This is the first time a trinitarian has told me we need to stop thinking of three persons, by the way. This is almost as good as Brandon’s wacky attempt to claim that P can be P and not-P simultaneously.

JT Paasch wrote:

“I’m not proposing that the persons have distinct mental acts. I proposed the opposite: namely, that the persons have the numerically same mental life, and that involves having at least some of the (numerically) same mental activities.”

Hi JT,

I’m trying to grasp what you mean. How does this apply to the thoughts of Jesus during his crucifixion?

Hey Scott,

I’m not proposing that the persons have distinct mental acts. I proposed the opposite: namely, that the persons have the numerically same mental life, and that involves having at least some of the (numerically) same mental activities.

The point I was making is this: one could argue that the persons have distinct mental powers but still share some of the same mental activities.

So I guess I’m questioning your idea that having identical mental powers is a necessary condition for having an identical mental life (or that having distinct mental powers is a necessary condition for having distinct mental lives). I don’t see how that is obvious, or at least I think it needs more of a metaphysical story to back it up.

What do you think about multiple personality disorder? Presumably, that involves one set of mental powers but many first-person POVs, right? I don’t know enough about psychology to know if that’s true, but if it is, then we also couldn’t say: ‘if distinct mental powers is a necessary condition for distinct first-person POVs, then one set of mental powers is a necessary condition for a single first-person POV’.

@JT: The metaphysics of such a proposal would indeed be ‘interesting’. The “that” in the second to last sentence in #25, refers to the proposal that the persons have numerically distinct powers and acts. Such a view I take to be some sort of Arianism. But to say they share numerically the same mental act, might lead away from the Arian family, so to speak.

The topic that got this off the ground was how many first-person points of views are there? My observation is that many contemporary theologians who want there to be three first-person pov’s posit that the persons have numerically distinct mental powers. I take it, then, that there are several first-person pov’s only if there are numerically distinct mental powers. By positing numerically distinct mental powers, we posit a necessary condition for several first-person pov’s. Given your suggestion that an act of understanding could be communicable like the divine essence (I have my doubts), we’d need to revisit the requisite indices for such a first-person indexical (Kaplan has four indices: individual, time, place, possible world).

@Fortigun: You still allow that “a dog” is satisfied by this one dog, or that one dog. It could be that “a dog” refers to this dog Spike, or this dog Fido, or this dog Sparky. Likewise, “God is a person” can be satisfied by God the Father, or God the Son, or God the Holy Spirit. We need not think of these as “three persons” (a cardinal number), but as this person, this person, and this person (ordinal numbers: first, second, third).

Scott, the indefinite article is not indefinite in number, it is indefinite in referent; ‘a dog’ means one dog, not two dogs, and not ‘maybe one or more dogs, but I can’t be definite’.

Scott:

I mean numerically the same thoughts.

I don’t know about that. It seems no harder to accept than the idea that numerically distinct persons share the numerically same essence.

When I approach this question, I distinguish between power-packs and powers. The divine persons have the same power-pack, but not necessarily the same powers (e.g., the Father has the power to procreate, but the Son does not).

I’m not saying that I think the persons have distinct mental powers. I’m just suggesting that IF one said they did, that doesn’t necessarily entail distinct personalities any more than having distinct relationships entails distinct gods.

@Fortigurn,

Apologies for some subtlety. When you say, “God is a person” you do not restrict the number of persons. The indefinite “a” is, just that, indefinite. What would make this claim true is there is at least one person who is God; trinitarians claim that, yes, there are three persons, and each is God, such that any of these three ‘the Father is God’, or ‘The Son is God’, or ‘The Holy Spirit is God’, would make the claim ‘God is a person’ true.

So, I don’t take the dispute here to be about semantics- both parties agree that the claim ‘God is a person’ is true–where they disagree is what could make this claim true.

One a purely semantic level, trinitarians might say that ‘the Father is (a) God’, ‘the Son is (a) God’, and ‘the Holy Spirit is (a) God’. That is, the ‘is’ in ‘the Father is God’ is the ‘is’ of predication. But this is _merely_ a semantic claim. It doesn’t commit one to a particular metaphysical claim at this point. Metaphysically, trinitarians might say that F, S, and HS are essentially numerically the same thing as God without being identical (Leibnizian identity) to God. And, if you were to ask, ‘what, then, is identical to God?’ We’d need to query if you are focusing on divine powers when you say ‘God’, or if you are focusing on an agent. If the former, then the divine essence is identical to (in the Leibnizian sense) itself.

Dale,

By the way, perhaps your blog could have a page that explains how replies can include italics and “box” quotes.

Dale wrote:

“That is a legal concept of a person. Yes, for legal purposes we treat corporations and such as if they were selves. But it’s hard to see the relevance of that to theology.” (Please excuse the lack of italics in this quote.)

First, no earthly analogy of the trinity is completely accurate while we still need analogies to try to understand God.

Second, legal analogies abound in the Bible. And legal analogy can help explain divine authority in the trinity.

Third, I know the comparison of human person and a corporate has major lack while it also illustrates the role of language in theological debate. For example, “homoousios” sometimes meant “person.” And this caused a temporary misunderstanding between the East and the West. And perhaps a lot of problems with debate about the trinity involve the ongoing evolution of language.

Fourth, the trinity is personal and not abstract.

Fifth, the trinity is not three separate persons in the exact way that Peter, Paul, and Mary are three separate persons, which goes back to my first point.

Six, “God” and “Lord” in the Old Testament are typically personified.

Anyway, for the last 2015 or so years, God is a human. But not 2020 years ago. Could I even say that God was once a zygote?

Dale wrote:

“Myself – I think that’s deliberately misleading, and amounts to having it both ways. Lots of things are in some ways like a self – a married couple, Siamese twins, a football team, a country – but if we *constantly* personified it, we would mislead.”

Does this mean that if I don’t constantly personify the trinity, then I’m not misleading?

If that is the case, then if I sometimes analogize the trinity to an indivisible partnership or an indivisible divine community. Likewise, I suppose that I’m not misleading. Or would you disagree? Or would you shred those analogies for some other reason?

No Scott, trinitarians believe that God is three persons. That’s the whole point of the ‘tri’ in ‘trinitarian’. Unitarians believe God is a person, trinitarians believe God is three persons. Trinitarians believe that God is an inexplicable thing which has three persons, not that God is a person.

Of course trinitarians believe that ‘God is a person’. The Father is God, and is a person.

If there’s one thing trinitarians can agree on, it’s that they can’t agree on exactly what God is. Aquinas even said bluntly that he had no idea how to describe what God is. The most he could say was that God is three somethings and one something else. That seems to work for a lot of pew sitters, but it’s not exactly precision theological engineering.

As for being a person, trinitarians certainly do not believe that God is a person. That’s something else they agree on.

@JT: By “very same thoughts” do you mean numerically the same thoughts, or qualitatively the same thoughts? On the view that there are distinct persons with numerically distinct mental powers, it’s hard to see how the distinct persons with numerically distinct mental powers could have numerically the same thoughts. If F, S, and HS have numerically distinct mental powers, and THEN we assert that they have numerically the same (mental) acts– that seems a bit of a stretch. It’s hard to see why they wouldn’t have numerically distinct acts from numerically distinct powers. In which case, the persons would have qualitatively the same acts, but not numerically the same acts. And, if one posited that– it’s hard to see how it’s not some sort of semi-Arianism, i.e. ‘homoiousianism’. In other words, numerically distinct divine mental powers (e.g., three divine intellects) seems to entail polytheism.

On James’s legal concept of a person: it’s not a popular view, but I think it could be argued this is pretty close to the way Hobbes thinks of things, since he is certainly a Trinitarian (at least, he talks about God in Trinitarian terms) and he understands this in terms of his concept of personation. We accept a Trinity because, according to Hobbes, God is personated in a threefold way (although in some later writings he draws back from his strong early commitment to it):

The true God may be personated. As He was: first, Moses, who governed the Israelites, that were that were not his, but God’s people; not in his own name, with hoc dicit Moses, but in God’s name, with hoc dicit Dominus. Secondly, by the Son of Man, His own Son, our blessed Saviour Jesus Christ, that came to reduce the Jews and induce all nations into the kingdom of his Father; not as of himself, but as sent from his Father. And thirdly, by the Holy Ghost, or Comforter, speaking and working in the Apostles; which Holy Ghost was a Comforter that came not of himself, but was sent and proceeded from them both.

I don’t recall if he ever calls the whole Trinity a person, but the ability of many to be personated as one is essential to Hobbes’s political philosophy, so there would be no logical impediment to saying that each of the three persons is a Person and the whole Trinity is a Person.

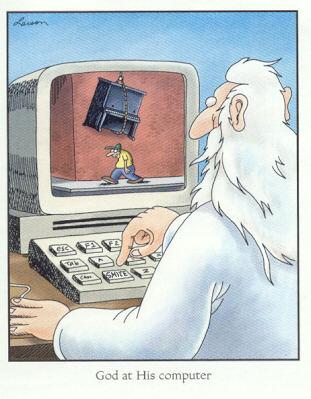

But most importantly, I want a ‘smite’ button on my computer too.

I’m not totally convinced that having distinct mental powers is enough to constitute distinct persons/personalities. Suppose three people, each with their own set of mental powers, went crazy go nuts with yoga and meditation, and they somehow hit a state of enlightenment where they all had the very same thoughts and loves — i.e., where they all shared the very same mental life. Would that really amount to three personalities?

I’m not sure. Maybe that would be more like one personality shared by three people. And maybe each of those persons could still have a first-person perspective on their shared mental life. Maybe they could each know what it is like to be the particular person that they are who has that mental life.

If that were plausible (I have no idea if it is), then perhaps it would take not discrete mental powers, but rather discrete mental lives to constitute distinct personalities. (Or, maybe these three enlightened persons could share their mental life, but if each of them had at least one discrete mental act on top of that, that would be enough to also make them distinct personalities — though maybe that would result in four personalities: one shared personality, and then three aggregate personalities composed partly of that shared personality.)

One could also turn this around. If distinct mental lives are all that’s required for distinct personalities, then do we really need distinct mental powers as well? Could three persons have the same mental activity power-source (the same thought/love generator, so to speak), but yet have distinct mental lives? If so, could there then be distinct personalities but one power-source? Alternatively, could one person with one power-source end up having distinct mental lives (multiple personality disorder, as it were)?

“I’m interested in hearing an answer from a trinitarian who says that the trinity is not a person.”

On a standard medieval view, roughly following Augustine and the Ps.-Ath. creed, we have the following.

1. The Father “is” God. The Father is a person. And, the Father is a person by virtue of himself or some essential personal property (paternity). So, the Father is not a person by virtue of the Son or the Son’s essential personal property (filiation) [even if it’s essential to the Father to be related to the Son].

2. Here, ‘person’ at minimum means that which has properties and is not a property of something else. This need not entail that the Father is a ‘self’ in the sense of having a first person singular point of view, namely “I”.

3. It seems that to have a first-person singular point of view, what is required is that the person in question has mental powers (intellect and will) and that such powers are numerically distinct from all other persons’ mental powers.

4. So, if the Father’s mental powers are identical with (or, at least essentially numerically the same as) the Son’s mental powers, then there are two persons but not two first-person singular points of view.

5. It seems that most accept this criterion [=C] for a person’s having a first-person singular point of view, [C]: person A has (can have) a first-person singular point of view, and person B has (can have) a first-person singular point of view just in case A and B have numerically distinct mental powers.

6. So, even if we have distinct (non-identical) persons, it doesn’t follow that we have distinct first-person singular points of view. The reason? This tradition has it that there is numerically one divine essence (numerically one divine intellect and will) that is ‘had’ essentially by the three persons. So, by virtue of denying numerically distinct mental powers, scholastics (at least) would seem to deny three first-person singular points of views when affirming distinct persons.

7. Would scholastics allow there to be a first-person _plural_ point of view, namely a “we”? That’s another question than the question, are there three first-person _singular_ points of view, namely “I”. Still further, it’d be interesting to see whether a “we” must presuppose an “I”? Interestingly, such questions seem to be surprisingly absent in much scholastic discourse on the Trinity.

James,

That is a legal concept of a person. Yes, for legal purposes we treat corporations and such as if they were selves. But it’s hard to see the relevance of that to theology.

There’s a big divide here – many trinitatarians do think God is a self – namely those with views that could be characterized as modalist. Unitarians tend to focus on those who think the ‘persons’ are so many selves – ’cause this isn’t monotheism (when those Persons are all divine, and equally so). But while some trinitarians assert in no uncertain terms that their “persons” are real persons/selves – e.g. most flying the ST banner – others strongly assert this to be naive, perhaps a consequence of “modern” notions of personhood being misread back into the patristic claims. Not infrequently, when Muslims or unitarians raise a ruckus about monotheism, these latter come out in force.

The answer to your question, I think, is that if you’re a ST person, it nonetheless sounds wrong to refer to God as ‘they’. Thus, we call them ‘God’, and the justification is a doctrine of analogy – this term fits because this group is *like* a self. Myself – I think that’s deliberately misleading, and amounts to having it both ways. Lots of things are in some ways like a self – a married couple, siamese twins, a football team, a country – but if we *constantly* personified it, we would mislead.

The url reference didn’t make it:

Dave,

I’m interested in hearing an answer from a trinitarian who says that the trinity is not a person. Anyway, I believe that the trinity is personal. And depending on the many possible definitions, the trinity is a person.

For example, a definition of “person”:

“6: one (as a human being, a partnership, or a corporation) that is recognized by law as the subject of rights and duties”

“person.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2010.

Merriam-Webster Online. 3 August 2010

If God is not a person, why do Trinitarians insist on referring to Him in this way?

Throughout my entire debate with Bowman, he never referred to God as “they”; he always used singular personal pronouns. Yet at the same time he wanted me to accept that the Trinitarian God is three persons, not one.

Why are Trinitarians so inconsistent with their terms of reference? Is it because their doctrine leaves them with no choice…?

Dale,

I thank you for your self revelation in Posts 30 and 31. I suppose your papers and posts criticize fine points of various social trinitarians while I originally suspected that your criticism was more broad. My misunderstanding.

I look forward to when you’ll further clarify your own views of the trinity.:)

1. no

2. yes – whether hyp means “self” or just thing/entity/being

3. it makes them a pair – there no reason, biblically, to think that they are parts of some further self/thing

4. N/A

Hi Greg,

Yes, I have read it. I think it is a good book in a number of ways. In the end, it still sort of leaves us wondering exactly what “the” doctrine is, but it is a good overview of some recent theories about analytic philosophers, and offers some well-motivated criticisms of and suggestions of how to amend some recent theories by systematic theologians. The whole thing is clearly written. Philosophically, I think its biggest problem is the issue of monotheism – but I’ll say more about that later. I’ll be writing a book review of it, which I’ll post here.

They miss the mark in a number of places. I may do a post on these. But keep in mind that “my views” in this context are mainly my published criticisms of ST and remarks on mysteries. I’ve not fully expressed my views, and also, in a couple places I’ve said a lot more about some things, since his book was written.

Yeah, I think that’s my least favorite quote. 🙂 I think that because I didn’t mention some things (e.g. medieval views about analogy, or Jenson’s theory) some people have assumed I didn’t know about them. But at least in many cases I did – I just tend to ignore things I think aren’t to the point – even if some readers want to hear about them.

What I called the Radical Ref approach is just the view that we must interpret the Bible by reason – by what makes the best sense of the texts. There is no Magisterium which can stipulate what they mean, or require us to read them in certain ways, or literally change their meaning. The author’s intent is primary – though I will also allow for God’s additional meanings over and above the authors’. This is all to say: let’s scrupulously avoid eisegesis – reading our own ideas back into these texts. But McCall would agree with that. He seems to think I hold we should ignore historical theology and the creeds in the task of interpretation – which is just silly. Listening to those voices is a part of interpreting them by reason. But, I’ll set them aside when convinced they have a distorted view of the text – just like McCall does! In a way, I think he was just offended by my tone, or what I didn’t say – I didn’t sing the praises of the mainstream tradition. Of course, that’s because I have very mixed feelings about catholic thinking.

About persons – yes, I do think the Bible asserts God to be a self, not to be “personal” as McCall and other STers would have it.

I’m glad I didn’t beg the question. Whew!

Look – orthodoxy demands 3 “persons”. Theologians can be very… careful about what this means. But McCall, being a STer, plainly holds them to be selves. And each is fully divine. Ergo 3 divinities. That just *means* the same thing as saying there are 3 gods. Now his reply, in what you quoted, amounts to: “But the tradition *says* these aren’t 3 gods.” Well, this is an argument that Tom’s view is outside the mainstream tradition!

I was very surprised that Tom didn’t focus his philosphical laser beams on Bauckham’s central thesis. That’s all I want to say about it for now, other than that I do not think that Bauckham gives us good insight into actual NT christology.

Yeah, I’m working on a review, as I said. Will post it here. Am working on a long paper on Hasker, whose views are similar to McCall’s. And am actually working on a paper analyzing Bauckham’s thesis (that “Jesus is included in the identity of God”). The Hasker on is the most substantial – refutes his reply to my deception arguments, and considers his positive views, going into monotheism, whether ST is tradition, etc.

I should have used a technical term instead of “inseparable.” I should have said that the trinity is “simple” and “indivisible,” unlike any other social group.

Dale,

I also want to through in that my view of the trinity includes aspects LT. For example, I reject that three harmonious divine persons merely sharing the same divine substance makes them one God. For example, I believe that God is three inseparable persons, inseparable from everlasting past to everlasting future. However, in any other circumstance with the possible exception of conjoined triplets sharing vital organs, three persons made of the same substance can separate and go their own ways. But as ironic as it may sound to some people, the Almighty Father and Son and Spirit cannot separate and go their own ways. (Not that it might sound ironic to you, but perhaps to others.) In that context, the word “person” inadequately describes the Father or the Son or the Spirit. Perhaps giving a new definition to “quasiperson” or some other word might help. And I perceive the Gospels teaching something along the line of an everlasting past to everlasting future interpersonal relationship of the Father and Son while I’m unsure of the best wording to describe it.

Anyway, as I stated in my last post, I think that I could better understand many of your writings if I had a clearer understanding of your view of the relationship of the Father and Son in the Gospels, beyond that of sender and sent. And after more reflection, I suppose that your answer to my first two questions in my last post are no and no, but I’m unsure of your view and I’d be deeply indebted if you answered those questions.

Dale,

May I first focus on your response in Post 27? This could inform me to better understand some of your other responses.

Could I please have more information about your interpretation of the relationship of the Father and Son? Your answer (“God to his Son. Sender, sent.”) answers one aspect of the relationship. I’m sorry if I my question was too vague, but allow me to ask more clear questions about this. For example,

1) Are the Father and Son the same person?

2) Are the Father and Son two hypostases?

3) If your answer to question 2 is yes, then would that make them a group of hypostases?

4)If your answer to question 3 is no, then could you please explain the answer?

Please, I need to take some baby steps to understand this. Your answers to my above four questions would greatly help me to understand your view. And I deeply apologize if you answered these questions in papers that you posted and I overlooked those answers.

Thank you.:)

Hi, Dale:

I’m currently reading Thomas McCall’s new book _Which Trinity? Whose Monotheism?_ and I am curious about whether you’ve read it and, if so, what you think of it. More to the point, I wonder what you think of his critique of your views.

In it, he lays out your arguments against ST and has lots of positive things to say about your strictly philosophical points. However, he’s not so complimentary of your theological points or hermeneutics.

Specifically, he says that your “minimalist methodology” (MM) or “radical reformation approach” (RRA) which assumes “that the monotheism of Scripture prescribes belief in only one divine person while proscribing belief in multiple divine persons is painfully naive, and in light of the work of contemporary biblical scholarship such an assumption looks misguided indeed. Similarly, to conclude that the affirmation that there are multiple divine persons is equivalent to the affirmation that there are multiple deities is completely unwarranted in light of traditional Christian orthodoxy, and in doing so Tuggy comes perilously close to begging the question against ST” (95).

The contemporary biblical scholarship that McCall alludes to above is the work done by Richard Bauckham (e.g., _God Crucified_) and others on second temple Jewish monotheism.

What say you to these charges? Do any of the papers that you’re currently working on respond to these charges or anything else McCall has said.

Thanks.

Hey Scott,

Philosophy of language is a weak spot for me – I don’t think I’ve read that piece.

I’m not sure what you’re getting at… could there be one power with three points of view? Any power must belong to a being, right? So we’re asking could there be one being with three points of view?

A point of view could be like a way of dealing with the world – think multiple personality movies… But I think you mean, can one being simultaneously have three different points of view. My first reaction is: not if those involving having contrary properties. e.g. being in pain & not.

No – this is an important mistake about the view in question. Sure the *word* “God” might be applicable to all three. But if we ask what the one God is, the one source of all else, they say the Trinity – and it is a group (or in some cases, a thing – but not a self).

In my view, no, and no. But what does this have to do with the paper?

Keep in mind the target of that paper – “social” Trinity theories on which “God” names a group of three divine selves. So it looks like there would have been deliberate deceit – in causing the Jews to think that “God” is a self (which *on the theory at hand* it is not). As to speculations that the three would have to conceal the fact that they’re three, in the paper, I can find no reason to think that (other than, it’d give the “social” theorist an answer to this concern!)

God to his Son. Sender, sent. I’m not sure what you’re getting at.

Excellent– I’ve been thinking about this topic–given that I just wrote on it — or at least, what I take Henry of Ghent to say on the matter.

Have you found Kaplan’s article from the 1970s on indexicals of any help? It seems that we need to sort out the criteria, the indices, for a first-person point of view, right? And, (1) we’d need to see whether non-identical first-person p.o.v.’s require numerically distinct mental powers, right? (2) If there is numerically one mental power in God, does it follow that there is numerically one first-person pov? It seems to me that only once we’ve answered (1) can we get to (2).

If we suppose that ‘God’ stands for a determinate incommunicable agent, i.e. one agent, then it seems that we’d answer (2) by saying there is numerically one first-person pov. But if we think that ‘God’ stands for some divine person, e.g., three agents, then it might be that there are three first-person povs, even there is numerically one divine mental power, right?

Oops, I need to clarify that my last post commented only on “Divine deception, identity, and Social Trinitarianism.”

I went through your paper. I looked as it once before. I need more time in the future to pull something together when I have no other deadline. But here are initial thoughts:

“x” and “y” could be identical in every way except the letter “x” looks different then the letter “y”.

“Each is, in a sense, one third of God, in the way that a single player is one eleventh of a football team.”

This is vague and insufficient. I don’t see how we can divide a football team into equal parts. What social trinitarian ever said something like your above quote?

Also, if one partner in a US general partnership with three partners signed a contract, then legally the contract was not signed by one third of the partnership but by the entire partnership.

“(1)If ST is true, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit acted like Don, Jon, and Ron.”

This looks like a poor analogy and jumping to a conclusion based on a limited amount of information. God needed to strongly emphasize monotheism and the loving relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And God needed to progressively reveal the complexities of theology. This isn’t an issue of a lying accommodator. Some use the same logic and imply that theistic evolution couldn’t be true or God is a liar.

“Remember that according to ST, God is not identical to the Father; ‘God’ doesn’t name an individual, but is a term for a unique and closely united group of three divinities.”

“God” can be the name of the Father or the Son or the Holy Spirit or all three of them. Perhaps you mean to say that in some ways but not all ways, “God” and “Father” are not identical.

“Note that we’ve just slipped into talking as if the God of the Jews is the same individual as the Father. As we’ve seen, this way of thinking about the Father pervades the New Testament, but it is not consistent with ST, which holds that ‘God’ and ‘Yahweh’ aren’t names for the Father, but are rather disguised plural referring expressions referring to a collection of three things, one of which is the Father.”

ST can claim that “God” and “Yahweh” are sometimes names for the Father.

“Let g be the God of the New Testament.”

This is vague and insufficient. For example, social trinitarians believe that the God of the New Testament could be thought of as the Father or the Son or the Holy Spirit or all three of them.

Was it a deceptive charade when the Father said “This is my Son” during the baptism of Jesus and the Transfiguration?

Was it a deceptive charade when Jesus prayed to the Father at the Garden of Gethsemane?

Dale, may I ask how you interpret the relationship of the Father and Son in the Gospels?

For example,

What happened when the Father said “This is my Son” during the baptism of Jesus and the Transfiguration?

And what happened when Jesus prayed to the Father at the Garden of Gethsemane?

And how do you interpret Jesus submitting to the Father?

Or if you’ve written about this in a paper and I missed that, please let me know.

Comments are closed.