Last time we looked at a famous argument about Jesus. (If you’ve never had a course in logic, or if it’s been a while, you should review the linked definitions there of “valid”, “invalid”, and “sound” before proceeding – this discussion presupposes that you understand their meanings.)

Consider this argument:

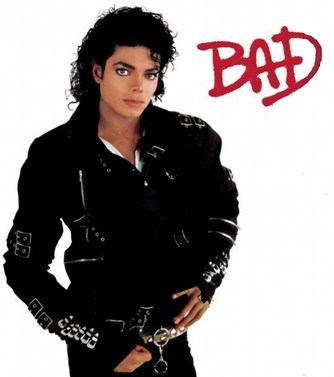

1. Michael Jackson is bad.

2. All bad people should be in jail.

3. Therefore, Michael Jackson should be in jail.

This appears to be a valid argument. Is it? It depends on what “bad” means.

Rewind to before we knew about Michael’s dirty deeds. Then, “bad” meant something like “cool” or “tough”. And I’m sure we’d all agree that premise 1 was true in that sense. ;-). How could premise 2 be true? We’d have to interpret “bad” there to mean “having committed a serious crime”. But then, 3 would not follow from 1 and 2; we would have a fallacy of equivocation. To make this painfully obvious, let’s rewrite the argument with the terms clarified:

1. Michael Jackson is cool.

2. All people who have committed serious crimes should be in jail.

3. Therefore, Michael Jackson should be in jail.

Now, never mind that 3 is true. The point is that 3 does not logically follow from 1 and 2. (In other words, it is possible for 1 and 2 to be true, while 3 is false.)

Of course, if we interpret “bad” is the same sense in premises 1 and 2, then the argument comes out valid. (We could then debate about whether it is also sound.) Here’s that valid argument:

1. Michael Jackson has committed at least one serious crime.

2. All people who have committed serious crimes should be in jail.

3. Therefore, Michael Jackson should be in jail.

This argument is valid. We can agree on that, and then debate about whether or not it’s also sound. (It’ll be sound if premises 1 and 2 are both true, which, given that it is valid, will imply that 3 is true as well.)

Now, back to a real man – Jesus. Here again, is the argument about him.

1. Jesus is divine.

2. There is only one god.

3. Something is a god if and only if it is divine.

4. Therefore, Jesus is the one god.

For this to be valid (for 4 to follow from the truth of 1-3), then “divine” and “god” must be used in the same sense throughout.

This is easier to see if we rewrite the argument using just one divinity term. (If we do this, we can discard the obvious premise 3.)

1. Jesus is a divine being.

2. There is only one divine being.

3. Therefore Jesus is the one divine being.

Alternately, we could rewrite the argument using “god” throughout.

1. Jesus is a god.

2. There is only one god.

3. Therefore, Jesus is the one god.

(Why am I not capitalizing the word “god” here? Because it is here being used as a kind-term like “human” or “dog”, not as a name like “George” or “Frank”.) I take it that these two arguments are equivalent.

Is the argument valid or invalid? It depends on what the terms mean.

- If “divine being” means one thing is premise 1 but something else in premise 2, there’s a fallacy of equivocation, and the argument isn’t valid. But if “divine being” means the same throughout, the argument is valid.

- Looking at the second version, if “god” means the same thing throughout, then the argument is valid. If not, it is invalid.

Once we’re sure we’ve got a valid argument, then, we can go on to ask if both premises are true, making a sound argument. But why should we be worried about equivocations? Doesn’t everyone agree on what “god” and “divine” mean? The answer to that is: absolutely not.

Next time: what does it mean to call something “a god” or “divine”?

Pingback: trinities - Jesus and “god” - part 11 - Review and Conclusion (Dale)

Pingback: trinities - Jesus and “god” - part 5 - Jesus as “god” in the New Testament (Dale)

Pingback: trinities - Jesus and “god” - part 3 - analyzing “X is a god” (Dale)

Pingback: trinities - Jesus and “god” - part 1 (Dale)

Comments are closed.