|

Listen to this post:

|

There is a vast disconnect between what some top-level modern scholars have thought about the meaning of John’s prologue vs. what the average Christian, or even the average seminary graduate, thinks about it.

For the many, this text is a slam-dunk support for “the deity of Christ” and even for “the Trinity.” It says Jesus is God, right? And yet implies that he’s a Person distinct from the Father who is eternally with the Father.

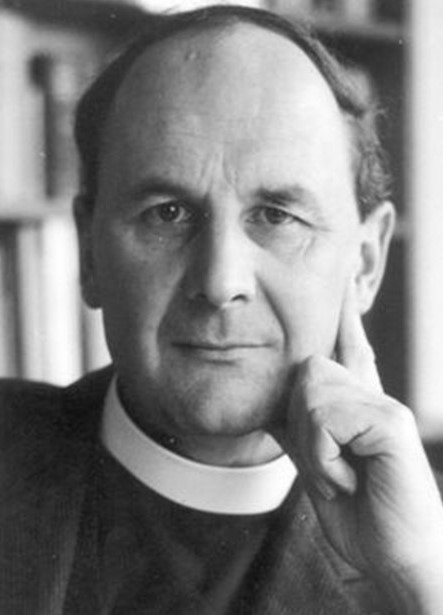

But there is a tradition going way back of taking this text to not even assume the pre-human existence of Jesus! A case in point is the influential New Testament scholar John A. T. Robinson (1919-83), in a review of James Dunn’s Christology in the Making in Theology (1982):

. . . I would say that John’s position is essentially contained in statements Dunn makes on p. 262 :

Initially at least Christ was not thought of as a divine being who had pre-existed with God but as the climactic embodiment of God’s power and purpose . . . God’s clearest self-expression, God’s last word. . . . The Christ-event defined God more clearly than anything else had ever done. . . . ‘Incarnation’ means initially that God’s love and power had been experienced in fullest measure in, through and as this man Jesus, that Christ had been experienced as God’s self-expression (italics his).

Dunn, Christology in the Making, 262.

This I believe is exactly what John sums up in 1.18 when he says that Jesus Christ as Son of God has given an exegesis of the Father. . . . What I contend John is saying is that the Word, which was theos, God in his self-revelation and expression, sarx egeneto [“became flesh”] (1.14), was embodied totally in and as a human being, became a person, was personalized not just personified. But that the Logos came into existence or expression as a person does not mean that he was a person before. In terms of the later classic distinction, it was not the Logos which was hypostatic (a person or hypostasis) who then assumed human nature as well as his own, but that the Logos was anhypostatic until the Word of God finally came to its full expression not merely in nature and in a people but in an individual historical person, and thus became hypostatic . . .

This distinction, I believe, is vital in order to guard John’s Christology, and our own, from the charge of docetism, to which it has so often been subjected . . . namely, that Jesus was a heavenly being, a divine person, living as a human, passing through this earth on the path of a parabola yet always a few inches off the ground. For John, I am convinced, as for all the other New Testament writers, Jesus is genuinely and utterly a man (he uses anthropos [“man”] of him more often than all the other Gospels together) who so completely incarnates God that whoever has seen him has seen the Father. This is precisely what John Bowker seems to be saying in the restatement in modern terms, considerably less pellucid than John’s, which Dunn commends (on p. 352, n. 7), of Jesus as ‘the wholly God-informed person’. ‘It is possible on this basis’, concludes Bowker, ‘to talk about a wholly human figure, without loss or compromise, and to talk also of a wholly real presence of God so far as that nature . . . can be mediated to and through the process’ of a human life. This quotation occurs in a footnote to Dunn’s statement (p. 265) that ‘we honour [John] most highly when we follow his example and mould the language and conceptualizations in transition today into a gospel which conveys the divine, revelatory and saving significance of Christ to our day as effectively as he did to his’. For prior to this (p. 264) Dunn shows himself uneasily conscious that the way John put it (as he interprets it) cannot really be ours today, and indeed that he was perhaps being taken for a bit of a ride by the ‘cultural evolution’ of the late first century.

It could be said that the Fourth Evangelist was as a much a prisoner of his language as its creator . . . That is to say, perhaps we see in the Fourth Gospel what started as an elaboration of the Logos-Son imagery applied to Jesus, inevitably in the transition of conceptualizations coming to express a conception of Christ’s personal pre-existence which early Gnosticism found more congenial than early orthodoxy.

Dunn, Christology in the Making, 264

I agree that this happened, but I believe it happened to John rather than in John, and that he was ‘taken over’ by the gnosticizers. In evidence I would cite the Johannine Epistles, which are saying in effect: ‘If that’s what you think I meant, that I was teaching a docetic-type Christology, denying Christ come in the flesh and trying to have the Father without the Son, then this is very Antichrist’. . . . Yet John is so near as well as so far. It is entirely explicable that he should have been taken in this way. For the ‘retrojective process’ was probably inevitable, which Geoffrey Lampe so well described in his God as Spirit, of reading back the revelation of the Logos as ‘a son’, that is, as a human being who perfectly imaged God, like an only son his father, on to the revelation of ‘the Son’, a heavenly being, later the second person of the Trinity, who took on a human nature. The content of the Christian revelation of God in and as an individual human person was combined with the cultural transition in late first-century Judaism and Gnosticism to the notion of fully hypostasized pre-existent heavenly figures to produce this result.

– John Robinson, “Dunn on John,” Theology 85: 322-38.

Bonus: here’s a video of Robinson giving an informal lecture on John that same year. At around 30 minutes, he actually talks about this review article!

A very interesting, thought provoking article. The bonus footage of Robinson addressing students was wonderful. I think he is a badly underestimated N.T. scholar.

Comments are closed.