|

Listen to this post:

|

In this post I want to briefly explain why I don’t think that Jude 5 credits Jesus with the exodus described in Exodus. The verse (NRSVUE) is:

Now I desire to remind you, though you are fully informed, once and for all, that Jesus, who saved* a people out of the land of Egypt, afterward destroyed those who did not believe.

* Other ancient authorities read informed, that the Lord who once and for all saved

The surviving Greek manuscripts don’t agree here. In fact, it’s worse than two readings (“Jesus,” “Lord”). Some texts also have “God,” and one even has “God Christ.” But these translators hedge their bets between “Jesus” (1st place) and “Lord” (2nd place – hence the footnote).

Perhaps the most important thing for a layperson to know is that the relevant experts are heavily divided; just look at these English translations. With this much expert disagreement, there will be no certainty in this matter, even for the experts. If one rigidly follows the rule of thumb in textual criticism that we should prefer the more difficult reading, one will go with “Jesus.” And all in all, looking at the oldest and best available copies, what is to my knowledge the most thorough scholarly investigation of the whole text of Jude says what most researchers think, that the reading “Jesus” has the strongest manuscript support. (Wasserman, The Epistle of Jude: Its Text and Transmission, p. 263)

Yet that is hardly the end of the story! That scholar continues, “but (the) lord and the god are attested in important witnesses, showing that the text suffered corruption early on.” (p. 263)

When an early corruption is likely, then it’s not enough just to point to the majority of (relatively but not absolutely) early texts that survive. Thus, textual critics launch into a very difficult game of inference to the best explanation. Which story is most plausible about one of those three readings being original, and then somehow the other two got produced by scribal mistakes and/or by deliberate corruption?

And here again, the top-level experts disagree! Thus you, the layperson, ought not to base any controversial doctrine on this verse, such as that Jesus was active in Old Testament times, something we don’t clearly see anywhere else in the New Testament.

Nor should you be persuaded by one-sided presentations in study Bibles. The always strongly-partisan-evangelical NET Bible gives us this note:

The reading . . . “Jesus”) is deemed too hard by several scholars, since it involves the notion of Jesus acting in the early history of the nation Israel (the NA27 has “the Lord” instead of “Jesus”). However, not only does this reading enjoy the strongest support from a variety of early witnesses . . . but the plethora of variants demonstrate that scribes were uncomfortable with it, for they seemed to exchange . . . “Lord” or “God” for “Jesus” . . . As difficult as the reading “Jesus” is, in light of verse 4 and in light of the progress of revelation (Jude being one of the last books in the New Testament to be composed), it is wholly appropriate. The NA28 text now also reads “Jesus”. For defense of this reading, see Philipp Bartholomä, “Did Jesus Save the People out of Egypt: A Re-examination of a Textual Problem in Jude 5, ” NovT 50 (2008): 143-58.

This, while impressive to the layperson, is far from decisive. Notice that they float the theory that the original “Jesus” made some scribes uncomfortable, who then changed it to “Lord” or “God.” But on the face of it, it is at least as plausible, in light of the Logos theories of the 2nd to the 4th centuries, that scribes, having accepted Justin Martyr’s new speculation that any seen or experienced “God” or “Lord” in the Old Testament must have been the Logos, the second god, not God (a.k.a. the Father), would have changed either “God” or “Lord” to “Jesus”! And citing one article that agrees with the editors . . . well, that’s not enough for the reader to make up her mind. And notice that the most widely used critical edition of the Greek New Testament, the NA (Nestle-Aland) in its 27th edition had “Lord” here but in its 28th edition has “Jesus” here . . . but who knows why!

Most importantly, though, they omit any explanation of why “Jesus” is considered “too hard” of a reading. Let’s briefly explore that. In my view these are relevant facts here which any diligent reader can observe, and taken together, I think they point us to a probably answer regarding Jude 5.

- First, we don’t see any other New Testament authors crediting the man Jesus with the exodus. But probably we would see that, had they believed it. Thus, they probably did not – and so probably Jude did not. So probably, “Jesus” is a corruption.

- Second, “Jesus” is the proper name of the man born to Mary, and this man was not around in the time of the exodus. This point is not decisive, since sometimes we refer to someone by a title or name they only gained later; e.g. the Fuhrer was born in Austria in 1889. But it is this man who is in view, as in verse 1 the author claims, by claiming to be the brother of the well-known James, to be the (half) brother of Jesus. And Wasserman observes that “Nowhere in the New Testament is the personal name Jesus applied to the pre-existent Christ.” (p. 264) Nowhere else, that is; thus, it is unlikely here in Jude 5.

- Third, and perhaps most importantly, this author distinguishes between Jesus and God, a.k.a. Yahweh (vv. 1, 4, 21, 25), and the texts he has in mind unambiguously ascribe the actions of Jude 5-7 to Yahweh: Numbers 14:10-35 (Jude 5); Genesis 6:1-4 (Jude 6); Genesis 18-19:29 (Jude 7). It’s God’s judgment which is referred to in this whole section.

- Fourth, many commenters have noticed that for whatever reason this author prefers the fancier “Jesus Christ” or “Lord Jesus Christ” or “Jesus Christ our Lord” (1, 4, 17, 21, 25), so it is surprising if he should use just the unadorned “Jesus” here.

Wasserman concludes,

In sum, the external evidence [i.e. the array of surviving manuscripts] is divided and corruption occurred early on. The reading “Jesus” has the best manuscript support and is indeed a difficult reading to the point of impossibility. I find it very unlikely that this early Christian author would write the simple “Jesus” if he had the pre-existent Christ in mind, especially in light of his style, and of the whole context of vv. 5-7. The ambiguous “(the) lord” on the other hand, could explain all other readings, which may represent conscious alterations or else copying mistakes involving nomina sacra [i.e. short, stylized abbreviations for important names and titles, like “God,” “Christ,” “Lord,” and “Jesus” – see Wasserman p. 265 or here]. Moreover, the typology Jesus-Joshua which became popular in the patristic era could have led a scribe to supply “Jesus.” I prefer the anarthrous form, “lord,” as original because of the weighty attestation of “Jesus” without the article.

p. 266 (emphases, links, and material in brackets added)

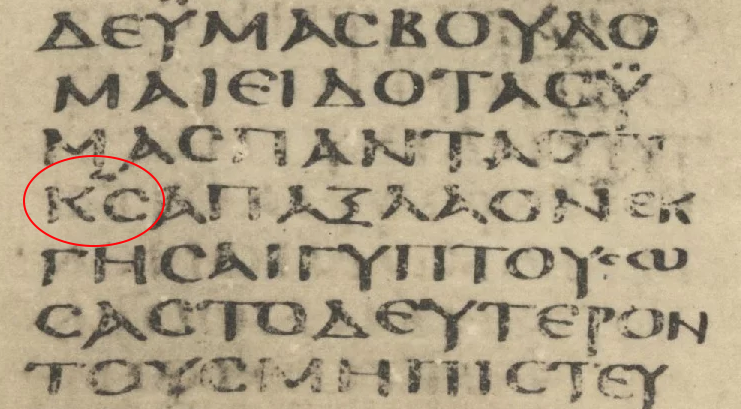

I have agree with Wasserman; “Lord” seems more likely than “Jesus” in Jude 5. Here is the reading “Lord” (kurios, abbreviated to KC with a line over the letters) in the important 4th c. Codex Sinaiticus.

Notice that Wasserman, like the NET editors, pre-supposes that Christ existed before his human career. But the former says that Jude 5 should mention “Lord” and the latter want it to be “Jesus.” Who’s right? If you think there is strong evidence that New Testament authors taught Jesus’ activity in Old Testament times, that may incline you to do with the NET editors; and yet, at best you should hold this conclusion very lightly! You must remember that scholars just as competent as the NET editors disagree with their note. For my part, I don’t think there is such evidence (and no, the 2nd Person of the Trinity is not supposed to be en-rocked in 1 Corinthians 10:4-5), and based on the considerations above, I have to agree with Wasserman and many other textual scholars that the original being “Jesus” here is “virtually impossible,” (Wasserman, p. 262), or I would simply say: unlikely.

Am I sure that the original didn’t read “Jesus”? No! I know that many with far more knowledge than me in these matters agree with the NET scholars. This is OK; I don’t need to base any controversial claims on this verse. The NET Bible editors here, and many like-minded traditionalists, need to fight for a pre-existence-implying reading here, as there are so few (arguably) clear texts to work with in the NT about that, and so every last little scrap must be made to count. Even so, many believers in Jesus’ pre-human career, may, wanting to maintain intellectual integrity, agree with Wasserman here. In this case the contexts of the wider passage and of the rest of the New Testament writings seem more important than manuscript considerations, which are in the end not decisive.

Check out pp. 162-168 on Hebrew subject gapping. It seems plausible to me that the original of Jude might be written in Hebrew. As noted here a Hebrew original does explain all the variations in Greek, Aramaic, Latin, etc. I would suggest the assumed subject gap to refer to God rather than Jesus. https://wixlabs-pdf-dev.appspot.com/assets/pdfjs/web/viewer.html?file=%2Fpdfproxy%3Finstance%3DDphyqq2QMSOGd0kfNN6SlnrZDHwp7ebGcxGxYfVfwnM.eyJpbnN0YW5jZUlkIjoiMmVlMTE3ODEtMmI0Ni00ZTJkLWI0NjYtOWM0OTU5NGZkMjgzIiwiYXBwRGVmSWQiOiIxM2VlMTBhMy1lY2I5LTdlZmYtNDI5OC1kMmY5ZjM0YWNmMGQiLCJtZXRhU2l0ZUlkIjoiYTIwNWFhZmUtM2NiNC00ZTQwLWEyZjItMGVmZGFhMDFlZWZjIiwic2lnbkRhdGUiOiIyMDIyLTA2LTI0VDAyOjQ3OjAzLjAzMVoiLCJ1aWQiOiJjNjhkYjk5NC1jODA5LTQzZDItOWM3NC01Zjk3MTIzM2IwZmQiLCJwZXJtaXNzaW9ucyI6Ik9XTkVSIiwiZGVtb01vZGUiOmZhbHNlLCJiaVRva2VuIjoiOGNlNGJkN2YtMTdmMi0wMDZkLTE2OTQtOTJiNGYzNGUzYzdmIiwic2l0ZU93bmVySWQiOiJjNjhkYjk5NC1jODA5LTQzZDItOWM3NC01Zjk3MTIzM2IwZmQiLCJzaXRlTWVtYmVySWQiOiJjNjhkYjk5NC1jODA5LTQzZDItOWM3NC01Zjk3MTIzM2IwZmQiLCJleHBpcmF0aW9uRGF0ZSI6IjIwMjItMDYtMjRUMDY6NDc6MDMuMDMxWiIsImxvZ2luQWNjb3VudElkIjoiYzY4ZGI5OTQtYzgwOS00M2QyLTljNzQtNWY5NzEyMzNiMGZkIn0%26compId%3Dcomp-kxfro4si%26url%3Dhttps%3A%2F%2Fdocs.wixstatic.com%2Fugd%2Fc68db9_e2a4a76045264e60b6b7f69c73f1c696.pdf&rng=1656044966531#page=231&zoom=75,-292,645&links=true&allowPrinting=true&allowDownload=true&originalFileName=The%20Hebrew%20Revelation%20James%20and%20Jude%20(small%20file%20size)%20-%20HebrewGospels.com%20-%201%2C3

Or Iesous means Joshua, and Jude was making a typological comparison.

One reason the Editio Critica Maior and the Nestle Aland 28 favor Iesous in Jude 5 is because of the Coherence-based Genealogical Method. Apparently the Kyrios reading had less coherence in its attestation which means it is more likely to have arisen multiple times.

Also relevant is the issue of word order. It seems likely that “you who know all things once for all, that [Kyrios / Iesous] having saved a people out of the land of Egypt, secondly destroyed those who did not believe” was changed to “you who know all things, that [Kyrios / Iesous] once for all having saved a people out of the land of Egypt, secondly destroyed those who did not believe” in order to create a parallelism between “once” and “secondly.” The problem is that no manuscript with Kyrios follows what seems to be the original word order. Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Athous Laurae and family 2138 read Kyrios but move “once” to before “having saved.” Byzantine manuscripts read Kyrios but change “all things” to “this.” There is no reason that any scribe would change the word order to that of Codex Vaticanus, Codex Alexandrinus, 33, 81, and so forth. The word order is probably one of the reasons the editors of the Editio Critica Maior and the Nestle Aland 28 chose Iesous over Kyrios.

Further the text of Codex Sinaiticus in Jude seems to have been produced via a comparison of multiple manuscripts. That is apparent from verse 3, where almost all manuscripts and versions read “our common salvation,” 1505, 1611, Syriac and Ethiopic read “our common life,” and Sinaiticus and Athous Laurae read “our common salvation and life,” a conflation.

Here is something I wrote in a recent article:

I can certainly envision a scenario in which a scribe, who was an ardent disciple of Justin, is copying portions of the NT, and comes upon Jude 5, which may have read Lord, which would have looked like ??1. But suppose the manuscript was damaged or worn in places and the scribe couldn’t make out the K, and remembering the passage in Justin’s Dialogue With Trypho in which Justin said, “For all we out of all nations do expect not Judah, but Jesus, who led your fathers out of Egypt,” he writes ??, which is how the word Jesus appears in the Greek manuscripts. This, of course, would not have been intentional on the scribes part. But I can also imagine how a scribe might be tempted to change an ambiguous ?? (Lord), which to his mind could refer to either God or Jesus2, to a ?? (Jesus) because it better supported his christological view.

Comments are closed.