Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 24 (Dale)

In chapter 24, Richard says that

In chapter 24, Richard says that

Certainly one and the same substance is not something greater or lesser, better or worse than itself. Therefore, [there are no inequalities among members of the Trinity] since one and the same substance is certainly in each. …for this reason any two persons [in the Trinity] will not be something greater or better than any one person alone; nor will all three taken together be more [great?] than any two or any one alone by himself… (p. 396)

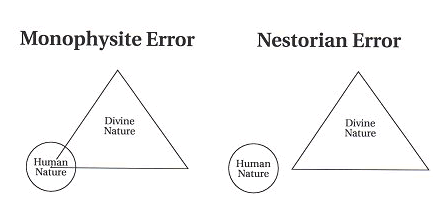

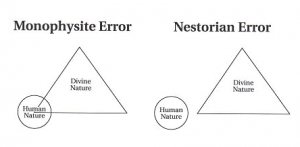

I take it that in the first sentence here that by “substance” he’s referring to the divine nature, saying that it can’t be greater than itself. That’s hard to argue with. He then argues that no person can be greater than any other. There’s an assumption here that greatness is solely a function of a thing’s nature. I’m not sure why we should accept that. Why not other intrinsic properties as well? One might think, e.g. it is greater to be the Father than it is to be the Son, hence even though they share the divine nature, one might think that the Father is greater than the Son. The inference from X and Y have the same substance to X and Y are the same in greatness, seems invalid. But if we make a valid argument, by adding the premise that greatness is a function solely of essence, we have valid argument, but then, Read More »Richard of St. Victor’s De Trinitate, Ch. 24 (Dale)