Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

Dealing with this inconsistent triad is hard for many. After a few podcast recommendations, I work through a long post by Reformed blogger Steve Hays, trying to find the beef. Unfortunately, it’s nearly all bun. He’s not able to formulate a response to this inconsistent triad, the subject of our previous episodes in this series.

Dealing with this inconsistent triad is hard for many. After a few podcast recommendations, I work through a long post by Reformed blogger Steve Hays, trying to find the beef. Unfortunately, it’s nearly all bun. He’s not able to formulate a response to this inconsistent triad, the subject of our previous episodes in this series.

1. Jesus died.

2. Jesus was fully divine.

3. No fully divine being has ever died.

Then I evaluate the brief response of a YouTube apologist to this argument:

1. God cannot die. (premise)

2. Jesus Christ died. (premise)

3. Therefore, Jesus Christ cannot be God. (1,2)

Finally, I consider a response to my inconsistent triad by Catholic philosopher Dr. Daniel Vecchio. This is carefully considered, and brings in many distinctions made by the tradition. I think it brings out the difficulty of figuring out what “the” classical catholic answer is supposed to be. In particular, terms like “Christ,” “Jesus,” and “the Son” are ambiguous, referring either to (1) the man (if there is a man in one’s christology), (2) the human nature (which is not a man), (3) the Logos (aka the divine nature), or to (4) the whole Christ, the person who has two natures. It’s not clear that any but the first of these could in principle die a human death, i.e. lose a human life.

Links for this episode:

- Interview 16: Church of God Vision (Seth Ross)

- The Areopagus Podcast (Facebook)

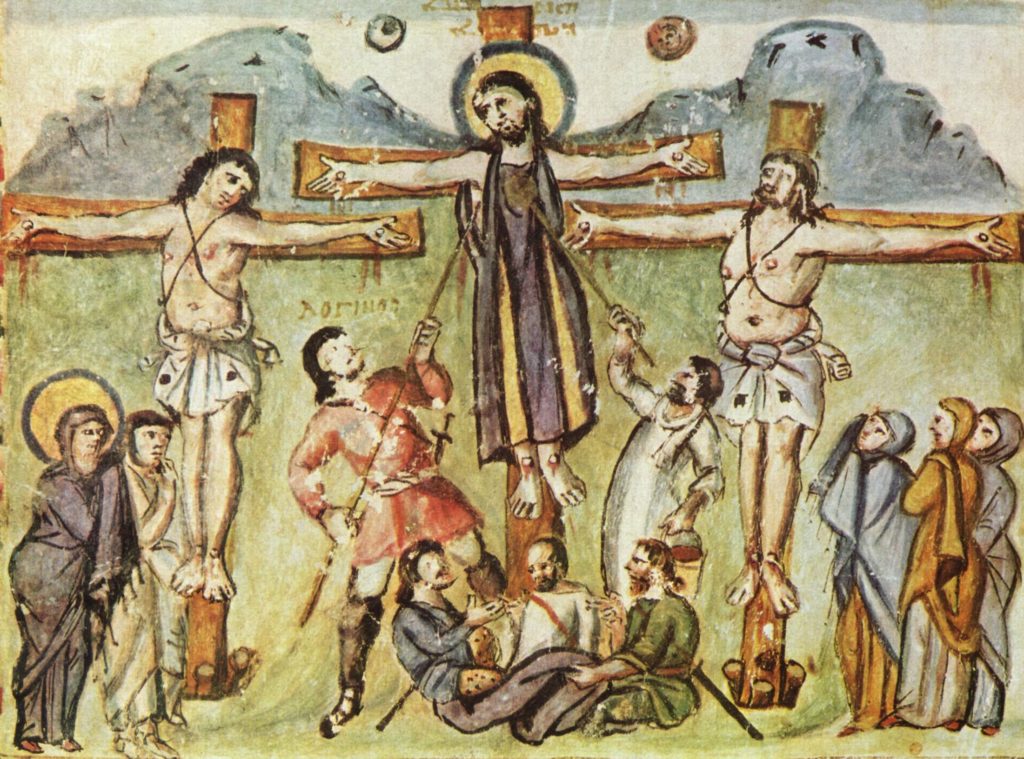

- podcast 145 – ‘Tis Mystery All: the Immortal dies!

podcast 178 – Apologists on how God can die – Part 1

podcast 178 – Apologists on how God can die – Part 1- podcast 179 – Apologists on how God can die – Part 2

- Steve Hays, “When God the Mighty Maker Died“

- “Can God Die?”

- Dr. Daniel Vecchio, “Tuggy’s Trilemma“

- This week’s thinking music is “It Was Only Yesterday” by Arne Bang Huseby.

I wonder, Dale, if a Thomist would have a better (or at least different) reply to the too-many-Jesus’s problem. A substance dualist thinks that a person is 2 substances, with 1 center of consciousness. A Thomistic dualist thinks a person is 1 substance having 1 essence yielding 1 center of consciousness. Doesn’t the Thomist want to say that Jesus is 1 substance, with 2 essences, and 1 center of consciousness? If so, wouldn’t that count as 1 person?

Dale, thanks so much for the work you’ve been putting into this series. It’s really taxing my brain (which probably isn’t saying a whole lot, come to think of it), and I’ve enjoyed it tremendously.

I grant that your trilemma is formidable. However, could that be that it seems so relative to the catholic [sic] position because it’s not having to do all of the work that the catholic position does? From your fantastic podcasts on the development of the early tradition, it seems to me that a key driver behind the development of that tradition was the need to account for how exactly Jesus’ death atoned for the sin of mankind, i.e. what was it about him that made his death universally effective, and how did he come to be that way? The traditional answer is the Incarnation, which of course leads to your trilemma. But if you reject the Incarnation, and accept that Jesus was not divine, then how is the atonement effective? You can say “It just is”, but that to me seems no less “mysterian” than those who attempt to reconcile your trilemma’s propositions with byzantine constructs like “hypostases” or “natures”.

Perhaps you could do a program on the Atonement under your form of Unitarianism, and how your approach addresses the questions raised by Atonement at least as well as (if not better than) the approach the Trinitarians took? Why did they feel it was so necessary to drink this particular cup if a simpler and more satisfactory alternative was available?

Hi RonH,

“what was it about him that made his death universally effective, and how did he come to be that way? The traditional answer is the Incarnation”

I would say that there is no one traditional answer to that. By itself, the creedal Incarnation claims are no answer. Rather, people suppose for different reasons that only a fully divine being could provide atonement. E.g. because only a fully divine being could divinize humanity, or because only a fully divine being is valuable enough to “pay” for all our sins.

For now, I content to point out that the NT says no such things as these. Nor are they self-evident. And such speculations bring their own problems with them. My own view of the atonement, I think, takes the biblical metaphors seriously. I don’t think anything was literally paid for. In a sense, it was up to God what he wanted to consider to be an appropriate sacrifice. I don’t think we’re going to find a theory which reveals how this was the only possible way anyone could be forgiven. In a sense, atonement theory is not a part of divine revelation, so I do think it is less important than the central claims of the gospel that we see, e.g. in Acts 2.

I have discussed atonement in a couple of older episodes, but I may do another one some time soon…

“I would say that there is no one traditional answer to that.”

Well, no one traditional atonement theory perhaps, but all the ones I’m familiar with still seem to hinge on Jesus’ divinity to work at all. There had to be something particularly special about him, otherwise we could all atone for ourselves (or at least each other). He was sinless, the only begotten Son of God, in whom all the fullness of deity dwelt in bodily form (Col. 2:9)… What does that mean? If your claim is that we don’t know, the scripture doesn’t tell us, and we’re better off not speculating about it, then I’ll grant that you may have a point. However, the Trinitarian can take the same stance when you press the point about how a fully divine being could die.

This is an interesting question about where to draw the “mysterian” line, because I don’t see how one avoids drawing it altogether. However, the idea that in the Incarnation God himself was entering the human experience for the purposes of saving us has proven to be an extremely powerful image. It is one of the most compelling aspects of the (Trinitarian) Christian story. That advantage might well offset the logical obstacle presented by your trilemma.

I know I’ve heard shows you’ve posted before on atonement theories. What I don’t think I’ve heard before is why the early Trinitarians were so committed to an idea which you argue not only lacks scriptural support but defies simple logic. Was there some kind of cultural pressure or historical event(s) driving it, much like the corruption of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in Luther’s day drove him to question the extent of the authority of the Magisterium? Modern Trinitiarians are (rationally) motivated to maintain consistency with their traditions and the communities based around them. But what about the first ones? Do we even have sufficient historical data to answer that question?

In my experience in the evangelical church world, I distinctly remember Bible teachers making the claim that, in the God-Man, God did what God cannot do on His own. God is infinite, but assumed finitude in the God-man. God is omniscient, but assumed limited knowledge in the God-man. God can’t die, but died in the God-man. What I consider the strongest illustration to show the incomprehensibility of the Incarnation, the baby in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger, was at the same time upholding the universe with the word of his power. I leave this to others to critique.

The comments above indicate an apparent contradiction where the double nature and/or Trinity is unfalsifiable. Therefore I reject this theory or hypothesis because it projects confusion on to the Gospel writers.

Comments are closed.