Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

In this episode I review our dueling definitions of the concepts trinitarian and unitarian, explain some criteria for a successful conceptual definition, and argue that Dr. Branson’s definitions don’t fare well according to these.

In this episode I review our dueling definitions of the concepts trinitarian and unitarian, explain some criteria for a successful conceptual definition, and argue that Dr. Branson’s definitions don’t fare well according to these.

Finally, I defend my definitions against his objections.

Dr. Branson’s definitions are:

(TB) A Trinitarian Theology says that:

(1) There are exactly three divine “persons” or individuals. Nevertheless,

(2) There is exactly one God.

(So, the persons can’t all = the One God).

(Presumably each one bears some important relation to the one God or has a “claim” to being called “God,” but our definition won’t settle how that works.)

(UB) A Unitarian Theology says that:

(1) There is exactly one divine “person” or individual, and

(2) There is exactly one God.

(Presumably these will just be identical, or at least “numerically one,” but again we won’t rule on that point in our definition.)

In contrast, in “Tertullian the unitarian,” I say,

A ‘trinitarian’ Christian theology says that (1) there is one God (2) which or who in some sense contains or consists of three ‘persons’, namely, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, (3) who are equally divine, and (4) (1)-(3) are eternally the case.

In contrast, a ‘unitarian’ Christian theology asserts that the (1) there is one God, (2) who is numerically identical with the one Jesus called ‘Father’, (3) and is not numerically identical with anyone else, (4) and (1)-(3) are eternally the case.

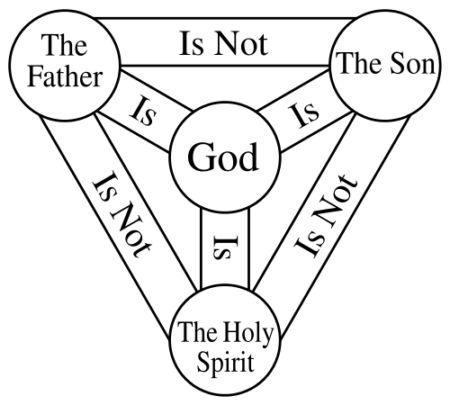

At a couple of points I bring up trinitarians who seem to hold a Trinity theory on which all the occurrences of “is” in ye olde Trinity shield would be understood as the “is” of identity (numerical sameness, =). It’s not a coherent view, of course.

At a couple of points I bring up trinitarians who seem to hold a Trinity theory on which all the occurrences of “is” in ye olde Trinity shield would be understood as the “is” of identity (numerical sameness, =). It’s not a coherent view, of course.

I also discuss this argument, which I attribute to Dr. Branson:

1. “Monarchical trinitarianism” is the view of the Trinity held by the Cappadocian fathers.

2. The true understanding of the Trinity (or the Triad) is what the Cappadocian fathers held.

3. The true understanding of the Trinity (or the Triad) should be called “trinitarian.”

4. Therefore, “Monarchical trinitarianism” should be called “trinitarian.” (1-3)

Links for this episode:

- David Kelley on How to Evaluate Definitions

- podcast 185 – How to tell whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God – Part 1

- podcast 186 – How to tell whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God – Part 2

- podcast 73 – Is Proverbs 8 about Jesus? Part 3

- trinitarian or unitarian? 7 – Origen uncensored

- podcast 24 – How to be a Monotheistic Trinitarian

- one-self trinitarians

- three-self trinitarians

- podcast 232 – Trinity Club Orientation

- This week’s thinking music is “Rescue Me (Instrumental)” by Aussens@iter.

If my understanding is correct, many of the pre-Nicene apologists believed the Father alone was God, but only in the functional sense, not in the ontological sense. The Father is functionally (hierarchically) above the Son, so He is God not only to creation but to the Son and Spirit as well. The Father alone is “God” *in that sense*. But ontologically, the Son is also God–that is, the Son, having come forth from the only true God, is by nature/inheritance “God.” Justin even calls Him “another God,” and Origin calls Him a “second God.” I suppose Justin and Origin could be accused of being tritheists, but if tritheism implies belief in three independent Gods, they were not tritheists. The apologists clearly did not think the Son and Spirit were independent of God. Instead, the Logos and Pneumos were aspects of the divine mind and came forth as distinct personal beings before or at the moment of creation. (Origin, of course, believed in eternal generation of the Son, but he still referred to Him as a “second God.”) If indeed the early apologists understood the Logos and Pneumos as aspects of the divine mind that, at some point, came forth as personal distinctions, then I suspect they would not have had a problem with the later fathers’ definition of “one God in three persons.” And, without contradiction, they could also speak of the Father as the one God and as God and Father of the Lord Jesus Christ. It all depends on what you mean by “God.”

Hey Vance – thanks for the comments. I don’t think we can spin the views of people like Justin and Origen and Tertullian as having the Father only “functionally” superior to the Son (or to the Logos). That’s a 20th c idea, merely functional (as opposed to ontological) subordination. For Justin and Tertullian, the Father literally existed before the Son, so the Son isn’t eternal. Can’t be a god, i.e. be divine in the way the one God is divine without being eternal. Origen holds to other ways in which the Logos is less than the unique God – none are functional, that I remember. I discuss a number of relevant passages in their writings here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Hnlw4iMhE8&t=1600s

Any translator who writes “another God” rather than “another god” – you see what he did there?

Origen makes a big point in his commentary on John about the difference between theos (a god) and ho theos (“the god” – we usually translate into English as “God”) – and his point is that “ho theos” can only be said about the Father, not about the Son. Why? Because of the *ontological*, not merely functional differences between God and the Logos. Some relevant quotes here: https://trinities.org/blog/trinitarian-or-unitarian-7-origen-uncensored-dale/

“came forth as personal distinctions” Well, this seems to be a manifest impossibility: at time 1 something is a property of God and at time 2 that same thing is an intelligent agent alongside God. https://trinities.org/blog/a-gnomes-tale/ The more clear-headed, like Tertullian, did not assert that. He is fairly clear that this idea of God’s externalizing his “Word” – really, in that, a new intelligent being comes to exist (the Son). I discuss the relevant passages here. https://trinities.org/blog/podcast-11-tertullian-the-unitarian/

So the issue between the 2nd c. guys and later trinitarians, e.g. Augustine, doesn’t really come down to different uses of the word “God.” One way to see it is to look at what they did when (because they were asserting in some sense the deity of the Son) when their monotheism was challenged. A trinitarian will argue that there is only one god because there is only one Trinity, or because the Persons have the same nature or essence, or because Father and Son are the same god. A unitarian will point out the uniqueness of the Father. This last is what the early guys do. Some relevant discussion and passages here: https://trinities.org/blog/podcast-24-how-to-be-a-monotheistic-trinitarian/ The non-monarchians – they all have God and the Logos as two beings, the first greater than the second, and the first being the unique God of the Bible – they hold the Logos to be a lesser, additional god. (Hence all the fuss from the monarchians – that’s one too many gods, and one too many creators!)

In “A Plea for the Christians,” Chapter X, Athenagoras writes:

“But the Son of God is the Logos of the Father, in idea and in operation [or, in ideal form and energizing power]; for after the pattern of Him and by Him were all things made, the Father and the Son being one. And, the Son being in the Father and the Father in the Son, in oneness and power of spirit, the understanding [mind] and reason of the Father is the Son of God…. He is the first product [first begotten] of the Father, not as having been brought into existence (for from the beginning, God, who is eternal mind, had the Logos [or, had His word and reason] in Himself, being from eternity instinct with Logos [or, being eternally rational]); but inasmuch as He came forth to be the idea [or, came forth to serve as ideal form] and energizing power of all material things…. The Holy Spirit Himself also, which operates in the prophets, we assert to be an effluence of God, flowing from Him, and returning back again like a beam of the sun.”

While it may be a “manifest impossibility,” this sounds like Athenagoras is saying that God’s word (which includes His reason and wisdom) was an aspect of God’s mind which somehow proceeded forth from Him to become a distinct person through whom God created the world.

Let me rephrase my earlier statement: the apologists believed that the Son was ontologically *similar* to God the Father, since (in their view), the Son was not created from something external to God, but came forth (was born, begotten) from within God Himself. Yes, we could argue that one who is begotten cannot be ontological identical to one who is unbegotten—hence the later Eusebian/Semi-Arian argument for homoiousios rather than homoousios—but the point is that the word “God” still applies, as the Son was brought forth *directly* from God (according to the apologists); He’s “God from God.” He may be “God” in some lesser sense, but (in their view) He’s still God, as He was born directly from God. (And if they were writing in modern English, they would most likely use the uppercase “G.”) If they were describing it in modern scientific categories, they’d probably say that the Son was produced from God’s own DNA. So this is what I was thinking of when I originally made the comment on ontological-vs.-functional categories.

But, no, the use of “God” as a hierarchical or functional term as opposed to the ontological sense is not a later development. The *language* may have developed, but the *concepts* were already there. They are in fact in Scripture itself. God is the “Most High God,” “God of gods,” “God over all.” He is “God” in the sense that He is the supreme Sovereign—the Almighty One who is above all else. There are other “mighty ones” (or “gods”) but only one *Almighty* One; and the Almighty One, according to the early apologists, brought forth from His own being a one-of-a-kind Son. The Son, therefore, is ontologically—i.e., in nature, kind—*like* (similar to) the Father, as His origin was in ho Theos Himself, but the Son is under the Father in authority.

I think the apologists, if they were here answering our questions, would tell us that the Father alone is “the one God” and “only true God” in the sense that there is one who is both ultimate Origin and supreme Sovereign—the First and the Highest.

At 50:45 you define Trinitarian view as “One God contains or consists of three Persons” and Dr. Branson’s view is not Trinitarian because he doesn’t affirm this. Now if that is your definition then none of the early catholic theologians were Trinitarians at least until some modern era. I am pretty sure that such a definition was never used by any Pro-Nicean theologians. I am absolutely sure that this was never a common or standard definition for them. Maybe you are getting something near to that in writings of Augustine. Your another mistake is that you assume that if someone says that Father, Son and Holy Spirit is One God then that is a denial of the creedal affirmation that “One God the Father”. You may be able to find statements similar to “Father, Son and Holy Spirit is One God due to one divine essence” in Pro-Nicean theologians even before Augustine but that is a defense against the accusation of Tritheism. This was never meant to be a denial of the creedal affirmation that One God is the Father. We know Augustine and following him later western theologians were quite uncomfortable with that and that is the source of modern view that “One God contains or consists of three Persons”. I don’t think any one even Dr. Behr or Dr. Branson would say that Father, Son and Holy Spirit are three Gods let alone the early Pro-Nicean theologians. I think you need to do a bit more homework 🙂

Thanks for the comments. The view that the one God “is” the Trinity, all thee of the together, is easily observed in Augustine, and is also in Gregory of Nazianzus, as I argued in the previous episode. They would not have liked my language of containing or consisting, because that would suggest the falsity of divine simplicity. But I add it to convey that there is supposed to be more to the one God than any one of the Persons alone – it’s three together that are supposed to be the one God.

About the one God the Father vs. the one God the Trinity: it doesn’t matter if one asserts both and does not intend that the one should contradict the other, given that we’re talking about numerically identifying things. If g = f, and g = t, then it would follow that f = t. But we all know that is false, for the Father and the Trinity (supposing there is such) would differ in several ways.

I suppose you will say that right-thinking Orthodox theologians assert that g=f, but not that g = t – but as I showed in the first part of my response to Dr. Branson, that is not true. A number of leading Orthodox theologians have asserted their belief that the one God is the triune God, and also, contrary to the story Dr. Branson tells, that their view of the Trinity is, filioque aside, basically the same as the “Western” views.

Comments are closed.