Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

Was the Council of Nicea (325) a defense and re-affirmation of core catholic theology? And did the Council of Constantinople (381) merely re-affirm Nicea, and slightly clean up its language and the details of its theology?

Was the Council of Nicea (325) a defense and re-affirmation of core catholic theology? And did the Council of Constantinople (381) merely re-affirm Nicea, and slightly clean up its language and the details of its theology?

In this episode, analytic theologian Dr. William Hasker gives his perspective on these fourth century events, reading from his Metaphysics and the Tripersonal God (discussed here and here). He contrasts a traditional understanding of these events with a clearer view based on careful historical investigation, such as that in Dr. Lewis Ayres’s Nicea and Its Legacy, and the sources I linked last time. And following Ayres, he discusses what “Pro-Nicene” theology is, as exemplified by “the Cappadocian Fathers.”

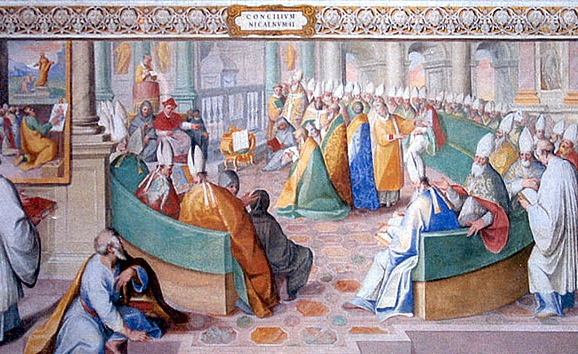

After Hasker’s discussion, I share a few thoughts on authority and tradition, sketching for your consideration a “thought experiment” about an imagined future ecumenical council, one which would give a new meaning to paintings like this one.

Thanks to Bill Hasker for his reading, and for his informative, high-quality work on this subject.

You can also listen to this episode on Stitcher or iTunes (please subscribe, rate, and review us in either or both – directions here). It is also available on YouTube (you can subscribe here). If you would like to upload audio feedback for possible inclusion in a future episode of this podcast, put the audio file here.

You can support the trinities podcast by ordering anything through Amazon.com after clicking through one of our links. We get a small % of your purchase, even though your price is not increased. (If you see “trinities” in you url while at Amazon, then we’ll get it.)

After a fine discussion of the Trinitarian controversy, I was rather disappointed to hear what followed. The answer to the thought-experiment is that this new doctrine is an obvious innovation, with no basis in either Scripture or tradition. It is thus in no way comparable with the pro-Nicene doctrine of the Trinity. As Hasker points out, the pro-Nicene teaching was not simply the teaching of the whole Church, until Arius started poisoning minds, as an older understanding had it. But it was one of several competing interpretations of ‘the faith delivered once for all to the saints’, and the one that the Church judged to be most faithful.

I would certainly maintain that ‘the door should always be open for the New Testament to correct later traditions’, but rejoice in the decline of ‘the spirit of Protestantism’, as you have narrowly defined it. Of course God is the authority, which authority is mediated in the person of Christ and his teaching to the apostles. But the apostles not only wrote their teaching down, but they preached it constantly, and taught others – not least of all, bishops – whom they had specially chosen to preach it too. Going back to the sources means not only going back to the Gospels, but going back to the Fathers – which is exactly what Hasker is recommending we do.

Hi Aiden,

Sorry – I was just thinking out loud – no transcript.

BTW I will interact more with your posts… have been a bit behind on blogging, doing a lot of writing, and other stuff.

God bless,

Dale

Pingback: Re-thinking the Arian Crisis | Eclectic Orthodoxy

Dale, might it be possible for you to either post the transcript of your remarks upon Hasker, with your thought experiment, or for you to email me a copy of them? I’d like to engage your thought experiment, but it’s difficult to do without having a copy of the transcript in front of me. Thanks.

Great episode Dale, loved the thought experiment.

Nestorianism (431) pronounced that Jesus is two distinct persons claiming two natures to actually constitute two persons. Again, we can see a common difficulty of understanding terms to describe proper Christology with the use of an ambiguous word, nature. Nestorius suffered from an indelible persistence that even some Protestants could appreciate. For Nestorius, Theotokos or God-bearer was a title for the holy virgin that seemed to him concisely inapplicable for an accurate understanding which would warrant a proper Christology. The title God-bearer completely ignores Mary’s role as a mother not to the divine nature, but rather the human nature of the Christ. In another sense the title over-esteems her role since the Holy Ghost conceived the Son. God was never conceived, at least the divine nature always existed, it was never born. Therefore, the holy virgin birthed the humanity of the Messiah, not his divinity, and should be considered the Christ-bearer, most aptly. Plainly a loaded question, but, “What part of her humanity could secure her son’s divinity?”, or as Calvinists put it, ‘the finite cannot contain the infinite’. (Utilizing undefiled logic, Calvin’s assertion, though it’s original intention was used to deny any real presence in a sacrament instead of highlighting the implication as it was employed by the Messiah, deserves general consideration). A fair argument indeed if one considers the gravity of a pre-existent divine nature clouted with immortality. Could it be that the virgin mother was found to be void of common properties that might distinguish her human-ness, her human nature? Was she in fact found to be without sin, highlighting yet another complimentary flawless human nature? This is not the appropriate time to extenuate the approximation divinity has to a perfect human nature, but it will be maintained here, anyhow, that the holy mother finds no place within the Trinitarian formula proper. What will be considered is the logical placement of Mariology.

It is interesting to note the patent dissociation shared by a majority of Protestant churches today with the early fifth century term Theotokos. What is ironic is the fact that the original reformers, whom the Protestants greatly esteem, embraced readily the doctrine of Mariology. Again, these persons of renown, Calvin, Luther and Zwingli etc. were reformers and not acting as theological profligates of secession from the Universal Church. They dutifully maintained the doctrine of Mariology prescribed by the Catholic Church holding to Mariology and other pillars of orthodoxy like it, sinlessness of the Virgin and her perpetual virginity, infant baptism etc.

This condition might be better identified as the reluctance to embrace selective forms of thought which have naturally developed within the evolutionary process of dispensation, identified as a form of schismatic negationism. The evolving doctrines have been severely limited in their logical pattern of growth. Take the dispensation of the incarnation of Christ established historically at the Council of Nicea 325 when the Messiah had been identified not as the son of God but rather as God the Son. Another progressive step in this process of dispensation would be that Mary was in fact the mother of God, or in the Greek, Theotokos meaning literally ‘God bearer,’ officially credited at the Council of Ephesus 431. Notably this is one year after the death of Augustine who is touted by Albert C. Outler, Ph.D., D.D. to have been at once ‘the last true patristic father’ and the ‘first medieval father of Western Christianity.’ It is Augustine who plainly defended the perpetual virginity of the blessed mother of Jesus ‘conceived as virgin, gave birth as virgin and stayed virgin forever, De Saca Virginitate 18, and ‘because of her virginity, is full of grace, De Sacra Virginitate, 6, 6, 191, despite straightforward evidence in Scripture identifying the Messiah as having many siblings in Matthew 13:55,56 and again in Mark 6:3 with reference to James the brother of the Lord in Galatians 1:19. While Augustine’s defense of the blessed mother’s perpetual virginity does not suggest he developed the doctrine of Mariology, he certainly made no effort to discourage a scripturally inaccurate portrayal of Mary the ‘Mother of God.’ Even in Psalms 69:8 we read prophesy of the Messiah who was to be alien to the children of his mother. To be sure it would become a complicated matter to suggest that Augustine operated in the Spirit whilst drumming the roll of perpetual virginity of the blessed mother despite the face of declared scriptural relevancy otherwise. His doctrines, though they are ripe with pagan ascription, have been promulgated as fit by staunch supporters, both Catholic and Protestant.

We have the incarnation of the Christ providing a doctrinal basis for Mariology, the adoration of Mary the Mother of God. It was not until the sixteenth century when the undertow of Protestantism began to surface and with it a developing tide of religious angst that heightened the swelling distrust of orthodoxy among religious philosophers and monks to the point of theological secession. What should warrant consideration is the fact that this lapse of time between measures would span a little over millennia. Why had so much time elapsed before anyone would blow the whistle on Mary worship or excessive veneration of Mary i.e. Mariolatry? Ordination of any dispensation for one-thousand years does require a second look eventually, at least some Protestant reformers thought so. But it would seem that Protestants would eventually embrace orthodoxy up to a point and fashion a ‘scriptural’ precursor that would yield dissent to the molded fashion or dispensation of the day. It does make sense to declare Mary the Mother of God after having established Jesus to be God. The question remains why Theotokos was not considered heresy by reformers in the sixteenth century since its inception, the middle of the fifth century. This prolonged acquiesce demonstrates the cavalier attitude towards the order of the day and in all fairness we must realize the length of silence to be rather cumbersome. Why wait a thousand years before speaking up and was there a considerable threat attached to those who demur, to those whose voice cries out heresy, to those who love truth more than their very own lives? What, if anything, does this credit orthodoxy for those centuries but religious despotism? If there were potential reformers that existed before the sixteenth century they either possessed enough common sense to value their own life above truth and kept silent or remained selfless and sacrificed their soul on the alter of truth leaving a putrid stain for all to see on the hands of the orthodox machine with its agencies furnished by the blood of the martyrs. The purpose for rhetoric of this sort is intended to flush out relative indifferences that exist today within religious circles. History has already warranted the value that most men have placed on their own souls and how much emphasis is placed on doctrines held by despots of varying complexity.

Now, returning to the natural progressive step relating to the incarnation of Christ we find that the development of Theotokos was met by a millennial wall of silence. Martyrdom first broke this silence in Paris, France, April 22, 1529 with the death of Louis de Berquin, a humble yet zealous evangelist of forty years. Berquin was the first in France to place his life beneath the value of the Gospel. Judged as he was to take issue with the doctrines of Rome, Berquin found refuge in the light of the Gospel and for this he was declared a heretic. If Berquin were to submit to recantation he was to undergo ritualistic steps of humiliation. With shaved head carrying a lighted candle, Berquin was to publicly perform penance in front of the Church of Notre Dame to God and the Glorious Mother, the Virgin. Afterwards his tongue was to be pierced and Berquin was to be put in prison for life without ink and paper to write or book to read. Berquin was charged with refusing to give proper title to the Blessed Virgin and invoke her name above, or in place of, the Holy Spirit. Unsatisfied with the option of denying his deep-seeded conviction while being bound the remainder of his earthly life to the uncompromising domination of orthodox regime he embraced the solace and freedom granted in the mortal persecution that lay in wait at the stake.

Shifting our attention ever so slightly northeast nearly the same period of time we find a contemporary reformer of Berquin. Martin Luther, the great German Protestant Reformer (1483-1546), is held in high esteem by many Protestants throughout the centuries for his historical issuance of the ninety-five theses (1517) which served as a source of antagonism for standard orthodoxy that endorsed, among other things, the sale of indulgences. Heightened by his proactive unorthodox stance, Luther also sets about by reclaiming the Holy Scriptures to be infallible over the Pope. This of course lends itself to the familiar solution that Luther adopted for salvation: God’s grace and faith in His Son. Small wonder is given to the stronghold that religious avarices may have held over the course of many centuries regarding salvation. From a Protestant perspective, an argument could be made for the damnation of an undisclosed amount of souls for an indefinite length of time while endorsing the embellishing sacraments espoused by orthodoxy prior to the Great Reformation. Recognized as a complete severance from the Catholic Church, the Reformation, if given a full view, will be identified more concisely as a splinter. The term severance would imply clear separation from a part, while splinter would connote a breakage, but not necessarily detached from the source, for if the Reformation could supply complete detachment from orthodox it would not have continued, among other doctrines, endorsement of Mariolatry. Connoting the marks of a Lutheran today we find noticeable dissimilarities in comparison to their esteemed progenitor who in fact was not trying to abandon the church but rather reform it. While it is quite possible that this fervent Augustinian Monk minted the phrase ‘Sola Scriptura,’ or ‘Scripture Only,’ some are left in marvelous wonder as to how effectual the veneration of Mary was to Reformers or would be Protestants of Luther’s day. Mariolatry remains an autonomous rubric woven into the very fabric of Protestant consciousness; it (the excessive veneration of the Virgin) is tied so closely and repetitively to the pattern of orthodoxy that it was innocently overlooked by some of the Reformers themselves. As a matter of evidence, the perpetual virginity of Mary who was admitted to be without original sin fell demonstrably from the works of many Reformers. Tying this link closely to a portion of their unorthodox posture should remind us of just how influential Mariology really was. Reverend Ganss dutifully balances the historical account:

‘The very confessions and very formularies of faith give the most positive and direct evidence that the Blessed Virgin once occupied an exalted position in their teachings; and, furthermore, that modern Protestantism is untrue to the tradition of its founders, -that it antagonizes and subverts its very charters of existence.’

Luther remained unhesitant to acknowledge Mary’s perpetual virginity while clarifying his perceived scriptural ambiguity, we read,

Christ, our Savior, was the real and natural fruit of Mary’s virginal womb . . . This was without the cooperation of a man, and she remained a virgin after that.

Christ . . . was the only Son of Mary, and the Virgin Mary bore no children besides Him . . . I am inclined to agree with those who declare that ‘brothers’ really mean ‘cousins’ here, for Holy Writ and the Jews always call cousins brothers.

A contemporary Reformer of Luther, Ulrich Zwingli with a resonant voice capitulates,

I firmly believe that Mary, according to the words of the gospel as a pure Virgin brought forth for us the Son of God and in childbirth and after childbirth forever remained a pure, intact Virgin.”

‘Interdum Scriptura’ might have been a more appropriate shibboleth for Luther whose pronouncements ironically continue to suffer exclusive Protestant suppression, intrepid pronouncements characterizing the sinless-ness of the Blessed Mother.

“It is a sweet and pious belief that the infusion of Mary’s soul was effected without original sin; so that in the very infusion of her soul she was also purified from original sin and adorned with God’s gifts, receiving a pure soul infused by God; thus from the first moment she began to live she was free from all sin”

Today, Protestants fail to realize it is much too irrational to dismiss Theotokos after having embraced the mysterious and extra-biblical doctrine of the Trinity which formulated the Messiah to be God.

To this purpose, Theotokos has been delineated to provide an historical context in which ideas within the church have evolved over the course of time. To a greater degree, Mariology developed naturally from the summation of church councils and ecumenical creeds which have supplanted a remedial Christology. What is plain is not far from wonder. How did veneration of the saints soon develop from such a time as this? Whether this is stated rhetorically or from a sincere curiosity, the process continues to unfold; the matter for evolution of theological doctrines remains apparent when close attention is paid.

Sola Scriptura, though it was an honest cry, was bandied about primarily as a euphemism to subvert a limited percentage of the Catholic Church’s doctrines and not necessarily as genuflection towards an objective meaning of the phrase.

Returning once again to the heretical doctrine of Nestorius we find the Council of Chalcedon to have heightened awareness of the controversy by offering this abbreviated statement:

The Symbol of Chalcedon, which was the written statement of the council, basically affirmed four things: 1) Christ is True God 2) He is True Man 3) He is one person 4) The divine and human in Christ must remain distinct.

Statements like this might serve only to mystify the second person of the Trinity blurring the meaning of words. Christ is true God and he is true man, but they must remain distinct within the person. What is more, there are three persons, each possessing one solitary will, each identified as separate and distinct from one another, each fully God in themselves thereby advancing the meaning of three persons in one being into obscurity. The Council of Chalcedon blurred the meaning of two separate and distinct natures into one dichotomized person. Although this scarce explanation of the incarnation serves as an example of Christ’s earthly presence it does not, however, explicate what becomes of the formula, this configuration, at his death. Patripassianism would not admittedly allow the first person of the Trinity to suffer death, elucidating a heretical form of Modalism which suggests that there is no distinction in the persons of the Trinity. Within Modalism, this heretical form allows the person, whom the second member of the Trinity occupies, to remain indistinct to (an)other member(s). Are we to assume that what has remained distinct within the second person while he was alive became indistinct upon his death? We should take caution here to explore what it is that actually suffered death, for if the second member of the Trinity employs the divine will, the only will singularly available to all three persons of the Trinity, yet remains distinct in person, we are therefore obliged to consider exactly what part, what aspect, of the Trinity had actually suffered death. For if the second person, who is intimately attached to the divine will and nature, died, then a portion of the divine will and nature suffered death along with him, the second person of the Trinity. Mind you the divinity of the second person does not have his own will, but shares it equally with the other members of the being.

So, what died at the crucifixion, humanity and/or divinity, and did one person continue to remain distinctly one person during and after his death? At this point we know that reason shall not ever be satisfied, but know that men have done their best to remediate the inefficiency of It’s Word, that is the Being’s Word (scripture.) Further, if divinity, if divine nature/will suffered death, how then could it, divine nature, be described as brandishing the properties of immortality?

I can certainly appreciate the thought experiment applied at such a generous length for it provided a fairly vivid process that hinges nearly if not appreciably to the actual series of historical events. I could stir the pot with a piece that might echo, however faintly, these sentiments if you should find it acceptable. The submission would be in the form of a word doc.

As always, the careful work you present resonates with philosophical poignancy. It strikes a chord.

Hi Michael,

Sure, send it to me. I’m kind of overloaded, so I can’t guarantee a reply, but I will look at it.

Comments are closed.