Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

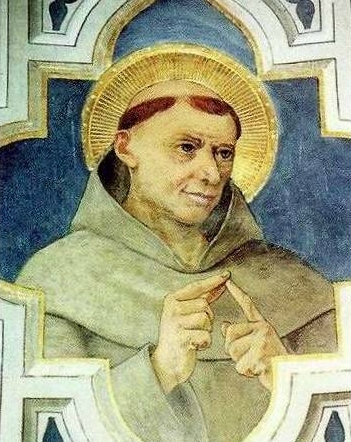

John Duns Scotus (d. 1308), nicknamed by tradition “the Subtle Doctor,” was one of the most important medieval Christian philosophers, and was notorious for the difficulty of his thought. In this episode, we hear a specialist in medieval philosophy give a conference presentation on Scotus’s views on identity (sameness) and distinction (difference).

John Duns Scotus (d. 1308), nicknamed by tradition “the Subtle Doctor,” was one of the most important medieval Christian philosophers, and was notorious for the difficulty of his thought. In this episode, we hear a specialist in medieval philosophy give a conference presentation on Scotus’s views on identity (sameness) and distinction (difference).

Nowadays most philosophers and logicians recognize qualitative sameness (aka similarity), which comes in degrees, and numerical sameness (aka numerical or absolute identity), which doesn’t come in degrees, and which is a symmetrical, transitive, and reflexive relation. This latter, numerical identity, is a relation which a thing can only bear to itself.

If these are all we have to work with, then we get apparent contradictions from trinitarian claims. For instance, consider this triad of claims:

- The Father is God.

- The Son is God.

- The Father is not the same as the Son.

If the Father is numerically identical to God (1), and so is the Son (2), then it follows (because the relation is symmetrical and transitive), that the Father and Son are numerically identical. (So, 3 is false) The above three claims, so understood, are an inconsistent triad – if any two are true, the remaining claim is false. But arguably, the “Athanasian Creed” requires them all.

That is, interpreting the above triad in terms of numerical identity, there would be this valid argument:

- f = g

- s = g

- g = s (from 2, symmetricality)

- f= s (from 1 and 3, by transitivity)

But 4 is a disastrous conclusion. We know that a thing can’t, at the same time and in the same way, differ from itself. But according to the New Testament, the Father and Son have differed. To put it differently, numerical sameness forces indiscernibility. If any A just is some B, then A and B can’t differ in the smallest way. But the Father and Son do differ, and so they must be non-identical, which is to say, numerically distinct. What does it mean to say, then, that each of them “is God.” Perhaps the statements simply mean that each is divine, that each has the divine attributes or a divine nature. Father and Son would then be not numerically identical, but rather similar – that is, like one another, in respect of being divine. But then we have two beings, each of which is divine; this would appear to be two gods. What now?

One response is to make additional distinctions, to argue that our concepts of numerical and qualitative sameness are not enough. This is the course pursued by John Duns Scotus. He holds that we must consider sameness and difference both in the mind, and as it were “on the side of things” in the world, and then he goes on to make further distinctions, which he thinks are relevant not only to theology, but also to more general metaphysics.

Our presenter is Dr. Joshua Blander, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at The King’s College in New York City. His paper is called “Being the Same without Being the Same: Duns Scotus on Identity and Distinction.” Here is his handout from the presentation, which will help you to follow along.

You can also listen to this episode on stitcher or itunes (please subscribe and rate us in either or both). If you would like to upload audio feedback for possible inclusion in a future episode of this podcast, put the audio file here.

Links for this episode:

- Dr. Joshua Blander

- John Duns Scotus

- previous trinities posts

- on identity

- on the indiscernibility of identicals (and another)

- on the minority view in present-day philosophy that there can be numerical sameness without identity

- episodes on “Before Abraham was, I am.” (John 8:58): episode 62, episode 63

- The Apostolic Fathers

Pingback: Depictions of Bl. John Duns Scotus - Absolute Primacy of ChristAbsolute Primacy of Christ

Dale,

looking at Josh Blander’s handout (for which you have provided the link) the the core seems to be something as fancy as “formal and adequate distinctions”.

No suprise Duns Scotus was nicknamed doctor subtilis.

I have not traced this in Scotus himself, but I have read it from different and reliable sources. According to these sources, Scotus’s “separability criterion” can be formulated like this: “two items are really distinct iff one can exist without the other”.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see as diverse application as the body-soul distinction, the divinity-humanity in Jesus, and, of course, the three “persons” of the Trinity …

I forgot to mention this other quote by Justin from Dialog with Trypho, chapter LX:

“…it will not be the Creator of all things [YHWH] that is the God that said to Moses that He was the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, but it will be He who has been proved to you to have appeared to Abraham, ministering to the will of the Maker of all things [YHWH]…”

Hi Dale,

Very interesting discussion on John 8:58 in the works of the early church fathers. I would suggest that while Justin himself did not apply this verse to Christ, he may well have laid the groundwork for such an application. The following is a quote from Jusin’s First Apology, LXIII:

“And the angel of God spake to Moses in a flame of fire in a bush, and said, I am that I am, the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob….He who spake to him was indeed the Son of God, who is called both Angel and Apostle…”

It seems likely that Irenaeus, as a follower of Justin, honed in on this and deduced a connection to the ego eimi in Jn 8:58. And the rest, as they say, is history…

Comments are closed.