In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

In round 5, Bowman aims to show that the “threefoldness” of God is implied by the Bible. At issue is how to explain “triadic” mentions of Father, Son, and Spirit (Or God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, etc.). Bowman mentions his list of fifty such passages. Here he focuses on a dozen passages. But first, his recap of where he thinks the debate is so far:

In the preceding three rounds of this debate, I have argued that the person of Jesus Christ existed as God prior to the creation of the world and that the Holy Spirit is also a divine person. If my argument up to this point has been successful, I have thoroughly refuted the Biblical Unitarian position and established two key elements of the doctrine of the Trinity. Add to these two points the premises that there is only one God who existed before creation and that the Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, and the Father is not the Holy Spirit, and the only theological position in the marketplace of ideas that is left is the doctrine of the Trinity. Since these are all premises that Biblical Unitarianism accepts, I have not defended them here. (emphases added)

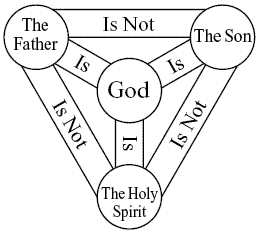

I’m tired of pointing out the inconsistency of what Bowman is urging. I’m capable of hearing the many ways theorists smooth away apparent inconsistencies (making subtle distinctions), but other than a quick gesture (I think in Round 1), I hear none of these familiar notes from him. This is just to say – he’s a resolute positive mysterian. Briefly, Father, Son and Spirit are numerically three, as they qualitatively differ from one another. But also, Bowman seems to think, each of them is numerically the same as God. This is inconsistent, because the “is” of numerical sameness is transitive – if f = g, and g = s, then f = s (compare: the concept of “bigger than”). Also, it seems that he thinks Father and Son to the same god, and also, since this god just is a person (hence “who” above), they are the same person as each other. And, of course, also they are not. Sigh. Let’s stick with the vague “threefoldness” claim I started with.

Bowman ignores what I call a kind of subordinationism in which the Son and Spirit are (take your pick) eternally generated, or created before the creation of the cosmos (this assuming that deity doesn’t imply aseity). This is in some sense within the “marketplace of ideas”, and is, unlike Bowman’s view, seemingly consistent – they, like Burke, identify God with the Father (and not with the other two). Moreover, some important unitarians like Clarke and Biddle have held a view like this. I suppose his reasoning is that the only kind of subordination really out there, is that maintained by Jehovah’s Witnesses, in which the Spirit is not a self. In this debate, I think it is fair to set this option aside, as Burke isn’t defending it. But speaking of those early modern unitarians, Bowman’s discussion got me curious about how they read the passage we focus on below, so I pulled some books off my shelf and found some interesting comments there.

Back to his main aim; he discusses a selection of twelve out of what he says are “over fifty clear examples” of texts in which there is a “‘triadic pattern‘ in which Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” (or similar terms) are mentioned together. (Interestingly, Clarke has a chapter on such texts – by his count, 41.)

Bowman is certainly right about this – this phenomenon is interesting (it is far more than a stylistic tick of some one writer), and demands explanation. He might have added that unitarians have a tendency to treat each passage in isolation – holding that none by itself implies a Trinity doctrine. But they need to do more than that – they need to have a competing, and better explanation of this phenomenon. Will Burke offer one?

Bowman leads with what many would take as the strongest or most important such passage:  Matthew 29:18, in which Jesus tells us to baptize “in [or into] the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”. It’s importance, Bowman urges, is confirmed by

Matthew 29:18, in which Jesus tells us to baptize “in [or into] the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”. It’s importance, Bowman urges, is confirmed by

…the many anti-Trinitarians over the years who have grasped at the straw that the fourth-century writer Eusebius supposedly testified to an original form of the text in which Jesus said to baptize disciples “in my name” instead of what we find in all of the Greek manuscripts. Many continue to repeat this claim today, though it is hard to find any contemporary scholars who will support it

This is a bit of a distraction, since as Bowman point out, Burke doesn’t argue this way. But I found some interesting things in looking into this.

First, the authors he’s referring to in their book (p. 455) give quotes from Eusebius, refs and all – this isn’t some sort of rumor. (However they don’t seem to give the ref(s) relevant to what Price alleges below.) Second, they point out something which Bowman well knows, and which United Pentecostals never tire of pointing out – which is that baptism in Acts is never described in any threefold way. This is a bit strange if the usual text is accurate, but in his book Bowman properly points out that Acts never gives any ritual formula for baptism.

Bowman no doubt considers this argument desperate because no extant early Greek texts have the non-triple reading. But is it hard to find scholars who endorse it?

I didn’t find it too hard. Robert Price translates the verse: “…train all the gentiles as disciples, baptizing them in my name.” (p. 176, emphasis added) In a footnote he explains,

Eusebius tells us he saw copies of Matthew pre-dating the Council of Nicea that had “in my name” rather than the now-familiar trinitarian “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” It is hard to resist the inference that a Nicene baptism formula, reflecting the newly minted doctrine of the trinity, was inserted into the text from that time on.”

Granted, Price is way out past the left of left-wing / liberal Bible scholarship. But he’s certainly for that reason no “biblical unitarian”.

The triple-reading is in the Didache 7:5, which is universally held to be pre-200 CE. But so is the simpler wording. (9:5) Is it there because it was in Matthew, or the reverse? It’s hard to be sure. I guess I’d stick with the manuscripts, though. It is possible that Eusebius was mistaken – it may have been in his day that much was being made of that text by the “pro-Nicene” crowd, and someone for polemical reasons or to harmonize with Acts changed the reading to “in my name” – which Eusebius then saw and mistook for an earlier copy.

Bowman accuses such unitarians of inconsistency – they deny that this verse implies the Trinity, and yet they consider it a trinitarian insertion (which therefore would imply the Trinity). But this accusation won’t hold up. Rightly, unitarians deny that the verse (with the normal triple text) logically implies the Trinity or key component claims of it. They may be within their rights to think it sort of suggests it or fits best with some Trinity doctrine though. (This is far from obvious, in my view, despite what Price says above. In any case, this position is manifestly consistent.) I don’t this this is right, myself, as I explain below.

Typically, the older unitarians simply accepted the text, and found a way to read it which is consistent with unitarianism.

What about the passage might imply the equal divinity of the Three, and/or their in some sense composing or being “within” God or the divine nature? The context of baptism? No – see 1 Cor 1:15 and 10:2. Their being mentioned together? No, see 1 Tim 5:21. (Belsham, pp. 232-4). To his credit, Bowman realizes that his case can’t be this simple; there are just rival expositions are interpretations, and the question is, which is the best?

Here’s how he argues:

If Biblical Unitarianism is true, the Father is God himself, while the Holy Spirit is an aspect of God, specifically his power. Thus, two of the three names in Matthew 28:19 denote either God himself or an aspect of God, according to Biblical Unitarianism. The middle name, however, supposedly refers to a mere human being (though the greatest of them all) whom God exalted to a divine status. This would seem to be a problematic way of reading the text.

Sorry, I don’t see a difficulty. We frequently group things of different categories. I love my computer, my country, my mom, and Monty-Pythonesque humor. But Bowman continues,

If we simply paraphrase Matthew 28:19 to express explicitly how the Trinitarian and Biblical Unitarian theologies understand its meaning, the difficulty facing the Biblical Unitarian will become clear:

Trinitarian: “Baptize disciples in the name of God the Father, the name of God the Son, and the name of God the Holy Spirit.”

Biblical Unitarian: “Baptize disciples in the name of God, the name of the exalted virgin-born man Jesus, and the name of the power of God.”Criticizing the Trinitarian interpretation based on arguments from silence ignores the fact that the Biblical Unitarian interpretation cannot simply repeat the words of the text without explanatory comment. Both views offer an interpretation of the text. The question is which of those interpretations best fits the text.

Indeed. I’m still not sure what the difficulty is, though.

Jesus says explicitly here to baptize disciples “into the name of…the Holy Spirit,” so that “Holy Spirit” is a name, like “Father” and “Son.” Anti-Trinitarians commonly assert that the Bible never gives the Holy Spirit a name and therefore he is not a person (at best another argument from silence), but Matthew 28:19 says explicitly that “Holy Spirit” is a “name.” This would seem to be very good evidence that the Holy Spirit is a person after all.

OK – Bowman thinks the words “in the name of” are important, and that they suggest(?) the personhood of the Spirit. Do they? Maybe. For example, if the idea is that one baptizes by the authority of each of the Three, that suggests that all three are selves. Suggests, but not implies – compare: “I arrest you in the name of the president, the governor, and the State of Texas.”

But I think it is a mistake to make too much of “in the name of” here. As a number of unitarians have pointed out, by considering parallel scriptures (I’m too lazy to list out the references or scriptures here – this post is too long), it is plausible to think that “being baptized in/into the name of X” means the same thing as “being baptized into X”. If this is right, the paraphrase for either trinitarian or unitarian would be: “baptize into the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit”.

But what does that mean? Those three aren’t liquids, so we can’t be dipped into any of them. The ceremony is an initiation into a community of disciples. I take it, to be baptized into X is to commit publicly to the teachings associated with X. So one can be baptized into Jesus, John, the death of Christ, etc. To wrap up my current take on this passage, there is only one set of doctrines in view here – that which has come from the Father, being delivered by the Son, and now confirmed and spread by the Spirit. It seems to me this thought is consistent with the Spirit being a self, but is also consistent with it being God’s power. One would refer to the same doctrines if one talks more simply, as in Acts, of being baptized into Christ, or in the name of Jesus, etc. This reading seems to sit well with v. 20, which brings up teaching. If I’m right, this passage can never be important positive evidence for either the trinitarian or unitarian (well, at least not this verse – as to the passage, arguably v. 18 is easier for the unitarian).

If this is right, then it doesn’t follow that the Spirit has a name. In any case, “The Spirit”, “The Holy Spirit”, “the Spirit of God” are at most titles applied to a self, but are not proper names like Rob, Dave, Jesus, or Yahweh. Nor is the passage, on my suggested reading, making any point about the words “Holy Spirit” – Bowman’s suggestions in that last paragraph, I suggest, and a dead end.

Finally, note that many commenters, and I possibly early interpreters as well, are distracted by the idea that this text is giving a baptismal formula; I think this is wrong-headed, and I believe that Bowman agrees. Assuming this is from the original text of the gospel, it is a general command to the Christian community – ceremonial correctness is just not in view.

As best I can tell, then, Bowman does not make the case that this verse “presents powerful evidence in support of the doctrine of the Trinity.”

But this is just one passage – perhaps a wider view is more helpful to his side?

Pingback: trinities - SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 5 – BOWMAN – PART 3 (DALE)

“… there is only one set of doctrines in view here – that which has come from the Father, being delivered by the Son, and now confirmed and spread by the Spirit.”

Oh, perfect!

In fact, that is how I see all of God’s activities, past, present and future. The plan is all God’s. He is the source of all things. But he carries out his purposes through his Son, by the power of the Holy Spirit.

I have to admit – I like the idea of “eternal generation,” because I think it makes sense of a lot of problems. I’m glad it is still in “the marketplace of ideas”.

Comments are closed.