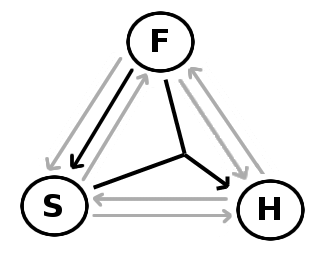

Dale’s Swinburne Trininty chart, version 2.0. (or 1.1 – whatever)

Thanks to reader (and Swinburne student) Joseph Jedwab for the correction. He points out:

[Swinburne] wants to avoid the idea that the Spirit’s existence is causally overdetermined [i.e. that it has two complete causes, either of which would alone suffice]. But he also wants to avoid the idea that each actively only partly causes the Spirit to exist. (comment on the previous post, accidentally deleted)

This seems right. I see Swinburne talking of the Father and Son as “co-causes” of the Spirit. It isn’t clear what co-causing is supposed to amount to (that their efforts are each necessary, but only jointly sufficient for the procession of the Spirit?), but that’s another subject. Above is a more accurate chart.

Technorati Tags: Swinburne, social analogy, social trinity, social trinitarian, procession

JT: My guess re: Henry is that he wants to say that the Son does not give the Father some new power by which the Father produces the Holy Spirit. So, with this in view, he’d say F per impossibile could produce the HS by himself w/o the S. I need to review the questions where he discusses this though for a ‘full report’ on this. I wouldn’t be surprised if Henry has similar sorts of reasoning as Swinburne–maybe not in as analytically nice terms, nonetheless.

I think the ‘mutuality’ thesis is driven by respect for Richard St. Victor and that love as a productive principle is ‘perfect’ if it is mutual love. So, on this view, perhaps, we can think of the Father’s own perfect love and that as ‘mutual love’ this is just another ‘mode’ of perfect love. Henry seems to use this sort of reasoning to say how e.g. the Father has perfect knowledge, though the Son has perfected knowledge qua generated (i.e. as a mode of perfect knowledge).

Scott,

Good point. It’s really just a question about what you’re trying to explain. What explains two products? Two productive acts. What explains two productive acts? Two causal powers. So Scotus is just locating the productive acts as the proximate a quo of the products, and the causal powers as the remote a quo of the products. The idea would be that two causal powers won’t explain two products unless those causal powers are exercised, unless there are productive acts. Without productive acts, you just have two dormant powers.

Also, your question about mutual lovin’ is good. I know that Scotus thinks the Father could produce the Spirit apart from the Son because the Father has that power in himself, independently of the Son (in the first instant of nature). The Son only participates, as it were, in the Father’s active spiration. (Of course, Ockham thinks this means the Son’s role amounts to causal over determination: if the Father has the power ‘before’ the Son, then why doesn’t he exercise that power ‘before’ the Son?)

Henry, I don’t know. I’ve only read the chunks of Henry that Ockham quotes on this topic, I haven’t read Henry on this topic outside of that (not yet). In those texts quoted by Ockham Henry really seems to think we need two, doing the mutual lovin’. Of course, Ockham’s selective quoting is probably a culprit here, but in any case, how does Henry think the Father could produce the Spirit apart from the Son, if mutual lovin’ is the ‘principiative’ source of the dual-procession?

Good posts Joseph and JT.

I agree with most all of what JT says about the medieval mob; distinction of origin according to agent-cause only distinguishes the persons, it doesn’t distinguish the number of persons; and further, Henry of Ghent’s developed arguments that distinction of causal powers may explain the distinction and number of productive acts by an agent-cause. But, what I’m not clear about is why you think Scotus doesn’t think the causal power by which the productive act is performed doesn’t explain (in some sense) why there two really distinct products. If we say Scotus minimizes the sort of power by which the agent does productive acts, is this not sliding into Ockham’s critique? I somewhat imagine that Scotus is in fact subtly heading toward Ockham, given his, what I’ve been calling, agnosticism toward the specific identity of the productive acts (notional acts)–whereas Henry thinks the productive acts ought to be specified as as ‘reflexive acts’ that count as productive acts.

Joseph: Does S speak of the particular causal principle as requiring two agents akin to Richard of St. Victor who (I believe) says that the reason there must be two co-causers (or in late medieval lingo, ‘two co-principiators’) is that the causal principle by which the two act must be ‘mutual love’, so given that both agents fully cause, they thus act as a ‘mutual cause’ bringing about the HS. Interestingly enough, both Henry and Scotus surmise whether we can say, per impossibile, that the Father alone could produces the Holy Spirit, and both seem to answer ‘yes’. This to my mind causes hesitation to sort out just what they mean by ‘mutual love’ as the one principle by which the Father and Son produce the Holy Spirit. [I’m sure though if I review the relevant texts, an answer might emerge.]

Joseph,

Very interesting stuff here. Two separate issues I find interesting here: (A) the distinction of the persons (or at least, the distinction of their causal relations), and (B) causal over determination.

A. The distinction of persons.

1. I like bringing in Aquinas’s argument for the filioque here: if we can only distinguish the persons by their caused-by relations, then S would have to be caused-by F, and H would have to be caused-by F + S. I think you’re very right to say that this argument is applicable for those who don’t think the persons have thisness.

2. There is the common criticism to the filioque argument: there could be a fourth person, call it B, who is caused-by F + S + H. And there could be a fifth person, call it C, who is caused by F + S + H + B. And so on, ad infinitum.

3. This criticism highlights that the filioque argument can’t be used to establish the number of persons, only the distinction of persons.

4. One might take an alternative approach to distinguishing the persons. One might say that in God there are two causal powers, call them x and y, which are different in enough in kind that they are not reducible to one another. One could say that the difference in kind between the powers (Henry of Ghent), or the acts of exercising those powers (Scotus), might be sufficient to distinguish the persons.

5. Or one might just say the causal relations themselves are different, and that’s sufficient. If x causes y and x causes z, then the x-y relation is different from the x-z relation simply in virtue of being different relations (Ockham).

B. Causal over determination.

6. If I thought the power-to-produce-H is a causal power of the divine essence (rather than F and S each having their own power-to-(partially?-)produce-H), and if I thought this power is either exercised or not (i.e., it cannot be exercised partially), then if F or S exercised the power, that would be sufficient to produce H. If both F and S exercised it, that would be causal over determination.

7. I could avoid the problem by saying that only F or only S exercises the power, or I could say that the power can be exercised partially, e.g., such that F exercises some of it, and S exercises the rest of it (Richard of St Victor? Henry of Ghent?), or I could say each of F and S have their own power, e.g., they either each have part of it, or they have all of it, but each exercise it only partially, so as to avoid causal over determination (Swinburne?).

8. Or I could say that F and S somehow jointly exercise the power, but such that there is only one act of exercising that power. I find that very mysterious, but it’s what some of the medievals thought we had to say (Aquinas, Scotus, Ockham).

9. If we do take the answer in 8, then we have to ask how many causal relation obtain between F and S, on the one hand, and H on the other. Are there two relations, one F-H and one S-H? It’s hard to see how that wouldn’t be the case. But if so, wouldn’t that mean we have two (partial or full) causers?

Dear Dale,

It’s a good question what co-causation is. I think S should say it’s just this: each individually doesn’t suffice but both jointly causally suffice for the effect. You may call this partial rather than full causation if you like. But there are two distinctions to make here. 1. A substance fully causes iff it causes and suffices for the effect, and a substance partially causes iff it causes but doesn’t suffice for the effect. 2. A substance fully causes iff it causes the effect, and a substance partially causes iff it cause part of the effect. In sense (1) F and S individually partially cause and jointly fully cause H. In sense (2) neither F nor S individually partially cause but both jointly fully cause H.

I don’t know that S explicitly denies that F and S causally overdetermine H’s existence. But he should for at least two reasons. First, it’s very odd to posit such causal over-determination. Secondly, suppose the divine individuals lack thisness and active causal relations alone individuate them. F actively causes S to exist. And any divine individual F actively causes to exist is S. So if F actively causes H to exist, H is S. Since H isn’t S, F doesn’t actively cause H to exist. So only if S actively causes H to exist is there an active causal relation that individuates H. But this isn’t direct active co-causation. So if the initial assumption holds, F and S can’t causally overdetermine H.

Best,

Joseph

Comments are closed.