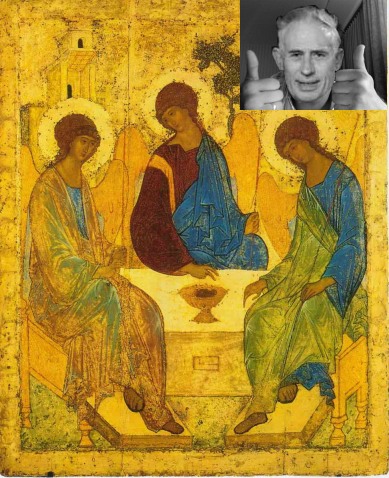

Swinburne sez: Two thumbs up for the social analogy!

Richard Swinburne is an Emeritus professor at Oriel College, Oxford University, and is widely considered one of the greatest living Christian philosophers. He’s done original work in philosophy of science, epistemology, philosophy of mind, and general metaphysics, but is perhaps best known for his work in philosophy of religion and philosophical theology. He has a way of squarely facing tough issues, and treating them in original and principled ways. He’s particularly well known by philosophers for his arguments for mind-body dualism, for his cumulative case for the existence of God, and for his bold social trinitarian theory, which I’ll cover in this series. I particularly enjoy his takes on moral matters, where I think he has a really fine touch. But I’d be hard pressed to say what my favorite book of his is. All I can say, is that I’ve learned a lot from him. I have fond memories of seeing him defend dualism in a most manly fashion, about ten years ago in California, in front of a very hostile audience of several hundred philosophy professors and students. In a sense, much of his philosophy of religion work is an exercise in apologetics – be he’s no mere verbal jouster, no lawyerly defender of the party line. He strives to go deep into the issues, and base his moves on well thought through philosophical positions. It takes a bit of work to see why he says all he does, but that’s what this blog is about – trying to give you a leg up.

Swinburne’s The Christian God contains his trinitarian theory. This theory is carefully crafted, and is notable for its clarity. Unlike many self-professed “social trinitarians”, he doesn’t content himself to say “God is sort of like three men, and sort of not” (never quite telling you in what ways the analogy does and doesn’t hold), or just “God is sort of like three men, but he’s really infinitely unlike three men” (whatever that means). No – he steps up to the plate, and boldly sketches out a theory which you can understand well enough to either agree or disagree with. And he’s certainly taken the heat for his clarity. He’s not unlike Moreland and Craig in this respect.

As with his other books in philosophical theology, Swinburne starts out by laying out some fundamental philosophical claims, which he then applies to the issues at hand. In this case, he has chapters on the concepts of necessity, substance, time, causation and “thisness”. In this series, in the interest of brevity, I’ll skip straight to his Trinity theory, explaining his purely philosophical claims only as needed.

As we haven’t discussed “social trinitarianism” here yet, let me say a few general things about it. There’s no precise definition of “social trinitarianism”. Indeed, many such theologians think they only differ in emphasis, or even just verbally from what they call the contrasting “Latin” tradition. (We’ve looked at a well-developed recent example of that in Leftow, and perhaps Brower and Rea can be put in that broad camp as well.) I would list the following as concerns distinctive of those in the “social trinitarian” camp.

- A concern to preserve the interpersonal relationships among the members of the Trinity, particularly the Father and the Son.

- Closely related, a desire to do justice to the New Testament, specifically its idea of Christ as a mediator and his loving personal relationship with the Father

- Suspicions that the “static” categories of Greek philosophy have in previous trinitarian theology obscured the dynamic and personal nature of God.

- Concern that traditional or Western trinitarian theology has made the doctrine irrelevant to practical concerns, such as politics, gender relations, and family life.

- The idea that to be Love itself, or for God to be perfectly loving, God must contain three subjects or persons.

I see the first, second and last of these in Swinburne, as well as one more concern, found more in philosopher social trinitarians – a desire that the doctrine be visibly consistent. He’s not content to leave apparent contradictions in place, unlike some social trinitarians, who also endorse what I call “mysterianism”. But that’s another topic.

Next time: Why there are three dudes on the cover of The Christian God.