|

Listen to this post:

|

I recently read a helpful new paper by Dr. William Lane Craig. Here are some quotes and comments:

. . . for the [second-century] Christian Apologists, God the Father, existing alone without the world, had within Himself His Word or Reason or Wisdom (compare: Proverbs 8:22-31), which somehow proceeded forth from Him, like a spoken word from a speaker’s mind, to become a distinct individual who created the world and ultimately became incarnate as Jesus Christ. The procession of the Logos from the Father was variously conceived as taking place either at the moment of creation or, alternatively, eternally. Although Christological concerns occupied center stage, the Holy Spirit, too, might be understood to proceed from God the Father’s mind.

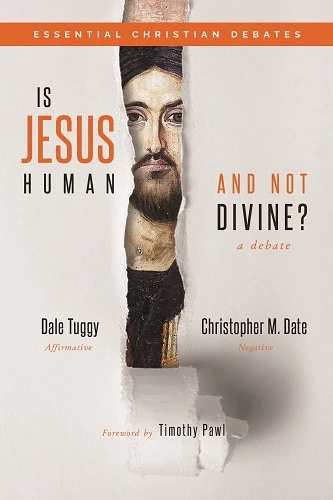

Right. Chris Date strongly denies this in our new debate book. He urges that for all such authors, the Logos is eternal, existing first as God’s reason, and then as a divine person. The catholic narrative simply demands that the eternity of the Son is a clear New Testament teaching, though it isn’t, and that more or less all Christians always believed in it. But these early Logos theorists, it seems for the most part, did not!

I point out that it seems obviously impossible that a property should turn into a person. Still, I concede, some of these authors may have thought that, although it seems to me that the better philosophers among them like Tertullian did not think that the Logos (the lesser divine being helping God to create) was the same person as God’s mind/reason/wisdom (inner logos). I claim that this is borne out by a careful look at what he says in Against Praxeas.

Back to Craig,

. . . According to this doctrine, then, there is one God, but He is not an undifferentiated unity. Rather certain aspects of His mind become expressed as distinct individuals.

Notice that Dr. Craig is charitably interpreting them as not saying that an attribute turns into a powerful, concrete self. He continues,

The Logos doctrine of the Apologists thus involves a fundamental reinterpretation of the Fatherhood of God: God is not merely the Father of mankind or Israel or even, especially, of Jesus of Nazareth, rather He is the Father from whom the Logos is begotten before all worlds. Christ is not merely the only-begotten Son of God in virtue of his Incarnation; rather he is begotten of the Father even in his pre-incarnate divinity.

Well said! This is to distort biblical ideas about the fatherhood of God.

. . . The Logos-doctrine of the Greek Apologists was taken up into Western theology by Irenaeus, who identifies God’s Word with the Son and His Wisdom with the Holy Spirit (Against Heresies 4.20.3; compare with 2.30.9). Tertullian not only accepts the view of the Greek Apologists that there are relations of derivation among the persons of the Trinity, but that these relations are not eternal. The Father he calls “the fountain of the Godhead” (Against Praxeas 29); “the Father is the entire substance, but the Son is a derivation and portion of the whole” (9).

Again, Craig, so to speak, sides with me over Chris Date. Date simply would not hear Tertullian’s explicit statements that the Father is older and greater than the Logos, who is only composed of a portion of his (material) substance. He chose to focus on what were ostensibly more trinitarian-sounding passages.

Back to Craig,

The Father exists eternally with His immanent Logos, and at creation, before the beginning of all things, the Son proceeds from the Father and so becomes His first begotten Son, through whom the world is created (19). Thus, the Logos only becomes the Son of God when He proceeds from the Father as a substantive being (7). Tertullian is fond of analogies such as the sunbeam emitted by the sun or the river by the spring (8, 22) to illustrate the oneness of substance of the Son as He proceeds from the Father.The Son, then, is “God of God” (15). Similarly, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son (4). It seems that Tertullian would consider the Son and Spirit to be distinct persons only after their procession from the Father (7); but it is clear that he insists on their personal distinctness from at least that point. In the East theologians like Origen also adhered to the derivation of the divine Son from the Father, although they maintained, in contrast to Tertullian, that the begetting of the Logos from the Father did not have a beginning but is from eternity. (pp. 23-24)

Dr. Craig is correct about all of this.

I would add that looking at all of Origen’s works, it is pretty clear that he thinks the three greatest beings are, in descending order: God, the Logos, and the Spirit. We could say that the Father gets the gold, the Son gets the silver, and the Spirit gets the bronze.

Now, Craig points out what seems to be an incoherence in the much celebrated “solution” arrived at by the later Nicenes, enshrined into law and tradition by Theodosius I in 380 and by the council he hosted in 381. Craig writes,

. . . although credally affirmed, the doctrine of the generation of the Son (and the procession of the Spirit) is a relic of Logos Christology which finds virtually no warrant in the biblical text and introduces a subordinationism into the Godhead which anyone who affirms the full deity of Christ ought to find very troubling. (p. 26)

By “Godhead” here Dr. Craig means the Trinity; he is saying that generation and procession imply inequality between the three of them, with the Father being the greatest. And he points out something which many apologists choose not to: that biblical scholars reject any alleged basis in the Bible for “generation” and “procession.” Guys like Athanasius who so merrily proof-text these doctrines are simply engaging in misguided eisegesis.

. . .This doctrine of the generation of the Logos from the Father cannot, despite assurances to the contrary, but diminish the status of the Son because He becomes an effect contingent upon the Father.

Right. Another way to put it is: given generation and procession the Son and Spirit would lack the divine attribute of aseity. As Dr. Craig says,

Even if this eternal procession takes place necessarily and apart from the Father’s will, the Son is less than the Father because the Father alone exists a se, whereas the Son exists through another (ab alio).

“Fathers” like Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa, of course, were aware of such objections. They simply denied that deity implies aseity. In my view, they were over-reacting against their theological opponent, the non-Nicene catholic Eunomius, who thought that unbegottenness was all of the divine essence, and so thought that we could know all of the divine essence. But never mind that – it seems to be part of the idea of a perfect being, and also just part of the monotheistic concept of a god, that such a one should exist independently of anything else. By definition a perfect being, or for that matter a “god” as understood in monotheistic religions, isn’t caused to exist by another.

You can download Dr. Craig’s entire paper from TheoLogica here.

Pingback: podcast 296 – Assessing Craig’s “Trinity Monotheism” – with Dale Glover – Part 1 – Trinities

And all of this Gentile speculation, to a righteous Jew, is a bunch of bull. A different God than Moses, Elijah and Isaiah knew.

Comments are closed.