This post is sponsored by the letter “R”.

This post is sponsored by the letter “R”.

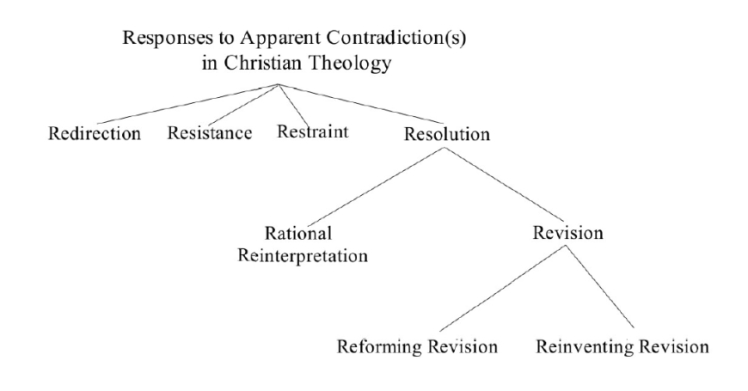

In my forthcoming “On Positive Mysterianism“, I first locate what I can “mysterianism” within a classification of various ways religious thinkers respond to apparently contradictory religious doctrines, i.e. ones which in their view they have some reason to believe.

In that paper I was discussing apparently contradictory beliefs about the Incarnation and Trinity doctrines, but it seems to me that this scheme is applicable to any religion.

The chart is just below.

(See pp. 1-5 here for the definitions.)

I recently read a fascinating little interdisciplinary book by Matthew Bagger, a professor at Auburn, called The Uses of Paradox: Religion, Self-Transformation, and the Absurd. Though I don’t agree with some of his main theses, I highly recommend this book. While I treat “mysteries” (apparent contradictions) as epistemic problems to be solved, or at least responded to, he hits the issue from a different angle, discussing thinkers such as Kierkegaard and Nagarjuna, who view apparent contradictions as an opportunity to get some distinctively religious benefit. They too see them as an epistemic problem, but for precisely that reason, they think them spiritually beneficial. An important part of his book is his distinction between “cognitive ascetics” like Kierkegaard and “mystics” like Nagarjuna. Essentially, the former view paradoxes as an opportunity for salvific suffering, whereas the latter view paradoxical beliefs as a ladder to some supra-rational gnosis.

Where do they fit on my chart? They’re both Resisters – they acknowledge the logical tension between the beliefs in question, but they think it should be upheld – neither ignored nor resolved by belief-revision.

I might call “cognitive ascetics” Reveling Resisters and Bagger’s “mystics” Reunifying Resisters. He doesn’t get into this too much, but it seems to me that all his examples (Daoist, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Neoplatonist) of the latter fit this broad schema: there’s a transcendent Source from which (in some sense or other) all is. By means of the apparently contradictory thoughts and beliefs, one can (in some sense) be Reunified with this Source.

Both, I think, are importantly different from the main Resister I discuss in my paper – Reformed philosophical theologian James Anderson. He thinks that it is intrinsically (epistemically) bad that one’s set of beliefs appears to be inconsistent. It may be that there are certain spiritual benefits to our being in this situation – primarily, humility, and seeing the vast gulf between God and oneself – which would make it overall a good idea for God to put us in this plight. But Anderson shows none of the profound desire to suffer by having paradoxical beliefs that is so prominent in Kierkegaard (Bagger, ch 2). Salvation is by grace, though faith – not by intellectual pain. Nor does Anderson hope to merge with the divine in some trans-rational meditative experience. So I think Mysterian Resistance is different from anything Bagger discusses.

I could come up with an all “R” synonym for Mysterian Resistance: maybe – Rational Resistance. I think James wouldn’t mind that. 🙂 More importantly, it seems to me that those I’ve called Negative and Positive Mysterians provide an epistemic response to this issue – roughly, that it is reasonable for us to expect that in thinking of the transcendent God (or Ultimate Reality) we should meet with paradoxes which in the end turn out to be barely intelligible claims (Negative Mysterians) or with firm and steady apparent contradictions (Positive Mysterians). Then I’d have: Rational, Reveling, and Reunifying Resistance.

Or maybe I’ll go all “M” for the species of Resistance: Mysterian, Merging, and Monkish Resistance.

What do you folks think? I’m inclined to go all “R”, especially since it was the letter “R” which sponsored this post.

Why the mania for alliteration? Just a heuristic device. But it could be argued that it’s evidence of a sick obsession with details on my part. 😉

James said, “I’m happy to confirm that I have no aspiration to merge with the divine in some trans-rational meditative experience. I doubt my wife would be very supportive of that sort of thing, at least while there remain uncompleted DIY projects.”

Perhaps you’re misinterpreting the possibilities; it might make you a better carpenter.:)

James,

If it were up to me, I’d award you an honorary degree in Humor. 🙂

“Rational Resistance”… yeah, it conjures up images of valiant Frenchmen fighting NAZIs. Rhymes with “National Resistance”.

I’m now thinking that “Rationalizing Resistance” is better – such folk are not necessarily rational, all things considered, but “rationalizing” in the sense of finding a reason or reasons why paradoxes should be endured intact.

I need to think more about the intrinsic badness thing. If it is epistemically bad for beliefs to be apparently contradictory, I think that those beliefs could still overall be epistemically good. Compare: pain is intrinsically bad. Yet a certain pain can be part of an experience which is overall good – e.g. eating hot salsa.

Now get back to those DIY projects, you lazy man!

So I’m a member of the Rational Resistance movement? I guess I can live with that. 🙂

But perhaps Reasoning Resistance would be even better, since it maintains the “-ing” pattern and avoids any hint of rationalism. (You know all about me and rationalism.)

I’m happy to confirm that I have no aspiration to merge with the divine in some trans-rational meditative experience. I doubt my wife would be very supportive of that sort of thing, at least while there remain uncompleted DIY projects.

I’m less sure about the differences you identify between my position and Kierkegaard’s. It’s true that I don’t revel in paradox and that I view theological paradox as a prima facie problem to be addressed (or at least, a limitation that we’re justifiably motivated to try to overcome). And I’ll admit I don’t have any profound desire to suffer, doxastically or otherwise!

Still, I’m not so sure that I see paradox as intrinsically epistemically bad. For all I know, prelapsarian Adam was faced with theological paradoxes as a result of his cognitive finitude; likewise for glorified saints. So I’d prefer to say that paradoxes per se are neither good nor bad, epistemically speaking; what matters is whether the beliefs in question are epistemically warranted, all things considered.

BTW, I’m also an ardent alliterationist.

Comments are closed.