Search Results for: relative identity

Exegetical neutrality

I am making slow (but sure) progress on The Same God? Reference and Identity in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Scriptures. My background is in the philosophy of language, and particularly the theory of reference and singular terms. The research for this book has taken me to some strange places I never expected to visit (and never really knew about before). One of those is hermeneutics,… Read More »Exegetical neutrality

podcast 252 – Fred Sanders on Seeing the Trinity in Scripture, and his Secret

Can we “see” the NT authors assuming that God is triune?

the dud of “corporate personality” or group persons

Chad occasionally talks in ways that suggest that I’ll actually alleging divine deception.

podcast 110 – Dr. Keith Ward on Christ and the Cosmos – Part 2

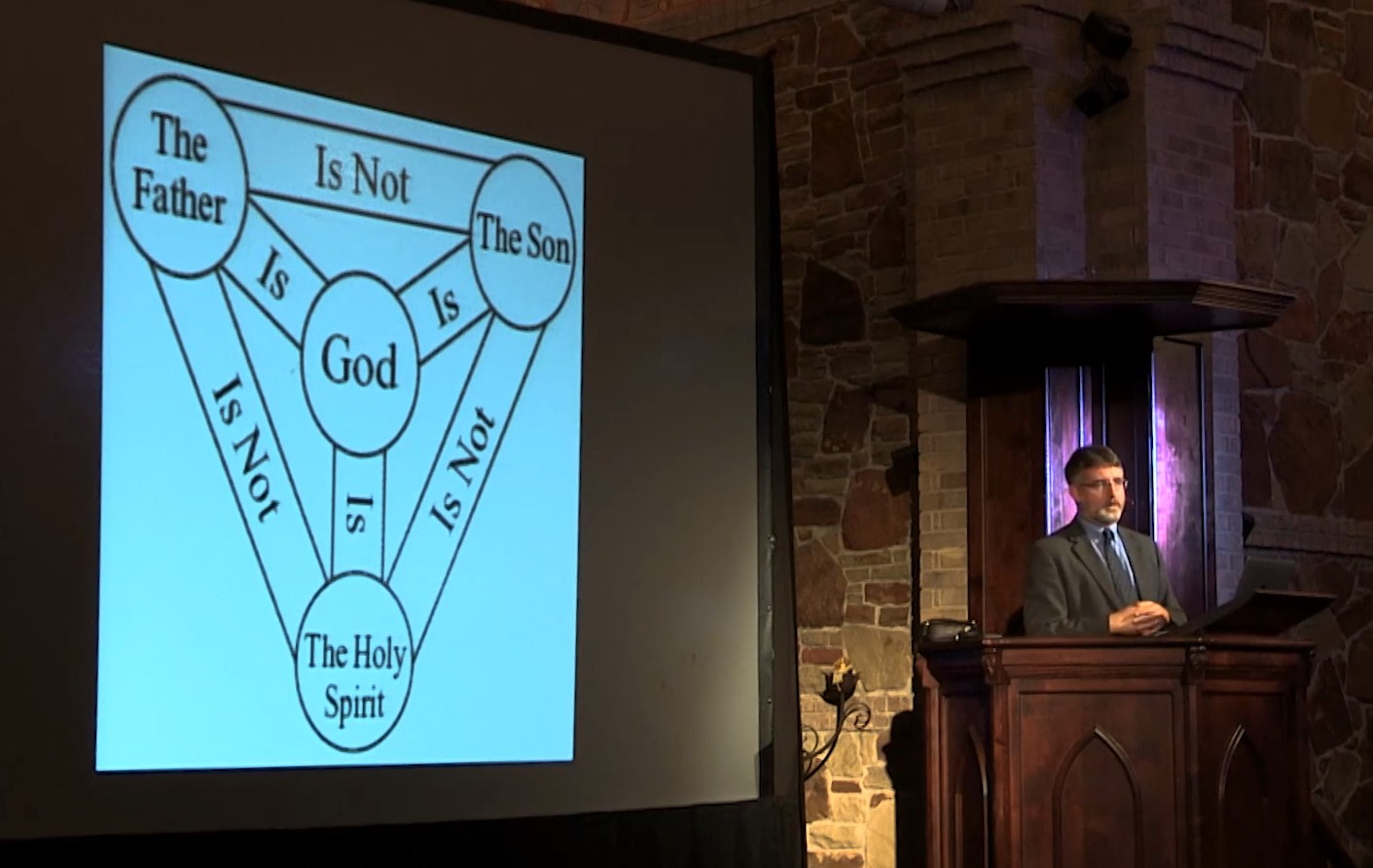

What does it mean to say that God is triune? Is this to say that the one God is a loving community of three divine selves? Or is there but one self common to the Trinity?

podcast 14 – One God, One Lord, Two Interpretations

The apostle Paul famously says, …for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Corinthians 8:6) Is this passage a radical transformation of, or a redefinition of Jewish monotheism? Is it an insertion of Jesus into the Shema confession, that… Read More »podcast 14 – One God, One Lord, Two Interpretations

podcast 149 – Dr. Larry Hurtado’s Destroyer of the gods – Part 1

Why did Roman rulers and polemicists find early Christianity so alarming, rather than just another religion?

Worship and Revelation 4-5 – Part 1 – setup

What, if anything, is wrong with this argument? 1. Only God should be worshiped. 2. Jesus should be worshiped. 3. Therefore, Jesus is God. (1,2) Before you answer, be sure you understand the claims fully. The “only” in 1 makes a claim of quantification, which we all understand in terms of identity. In standard logic, it would be analyzed as: Wg & (x)(Wx… Read More »Worship and Revelation 4-5 – Part 1 – setup

podcast 299 – Does the New Testament teach Trinity Monotheism? – with Dale Glover – Part 1

A conversation about whether or not the New Testament teaches “Trinity Monotheism.”

podcast 330 – Dr. Joshua Sijuwade on the monarchy of the Father

Does a doctrine of divine processions entail that the Son is less divine than the Father?

Did Jesus have faith in God?

“It’s stunning; there is nothing in the Bible that says Jesus had faith.”

the evolution of my views on the Trinity – part 6

Last time, c. 1998-2001, I was a social trinitarian along the lines of Richard Swinburne. While I was on the job market in 1999-2000, my former professor Stephen T. Davis was kind enough to invite me and a friend to attend the Incarnation summit, a follow up to the earlier interdisciplinary Trinity Summit. This was a great privilege, and I pretty much just observed. But… Read More »the evolution of my views on the Trinity – part 6

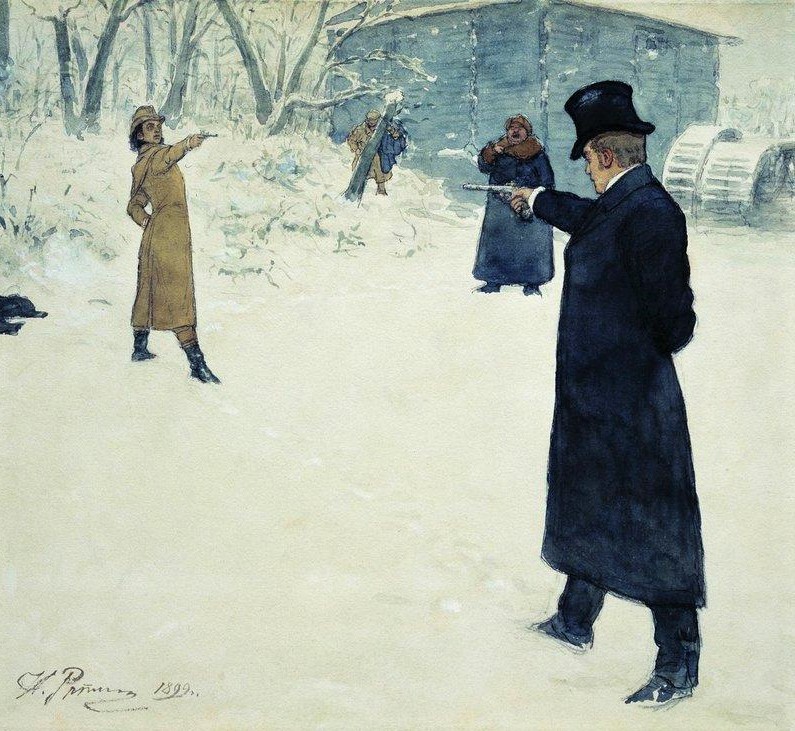

podcast 245 – Response to Branson Part 3 – Dueling Definitions

Weighing incompatible definitions of trinitarian theology and unitarian theology.

SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 6 Part 1 – BURKE

In the 6th and closing round, Burke argues from reason, scripture, and history. From reason: The Trinity doctrine, argues Burke, is inconsistent with itself. The “Athanasian” creed presents us with three, each of whom is a Lord, and yet insists that there is only one Lord. As some philosophers have pointed out, it is self-evident that if every F is a G, then there can’t… Read More »SCORING THE BURKE – BOWMAN DEBATE – ROUND 6 Part 1 – BURKE

podcast 100 – Dr. Larry Hurtado on God in New Testament Theology

Dr. Hurtado on his book God in New Testament Theology.

podcast 265 – What apologists don’t understand about the terms “being” and “Person”

Do I ignore “the” being/Person distinction?

podcast 123 – your official god vs. your actual god

What if the official god of your theology isn’t the one who actually gets his way in your life?

podcast 90 – Listener Questions 1

In this episode of the trinities podcast I answer some of your questions.

“Sabellianism Reconsidered” Considered – Part 4

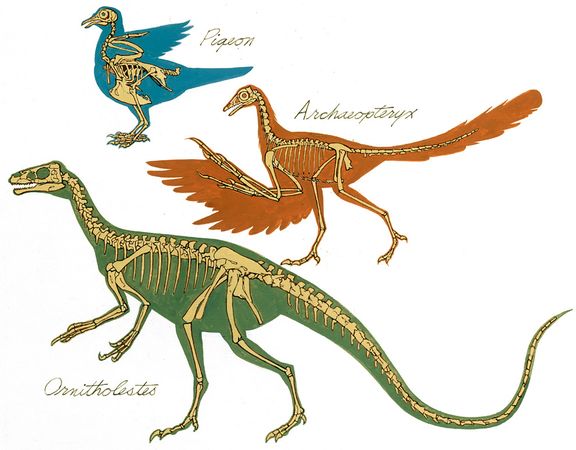

The theory, then, is that God is an everlasting, temporally extended thing with three temporal parts, each of which is a god. But, they’re the same god as God. Yet as we saw last time, how can the Three be gods at all, as each exists at some times but not others?

The theory, then, is that God is an everlasting, temporally extended thing with three temporal parts, each of which is a god. But, they’re the same god as God. Yet as we saw last time, how can the Three be gods at all, as each exists at some times but not others?Without going into the arguments for this controversial thesis, Baber appeals to the claim made by Derek Parfit and others, that “identity is not ‘what matters’ for survival”. (p.6) Thus, a future thing can count as my surviving, though it is not (numerically) identical to me.

Suppose (I’m stealing this thought experiment from Richard Swinburne) some mad scientists, such as Pinkie and the Brain, are going to cut my brain in half, and put the left half in one body, and the right in another. The body which gets the left half will be tortured to death, while the body getting the right half will be given lifetime passes to all NFL games and a lifetime supply of good beer. If I’m to undergo this experiment, I want to know which of these resulting people will be (numerically identical to) me: the unlucky one, the lucky one, or neither.

Baber (following Parfit) wants to say that depending on how exactly the resulting people are related to me, both may count as the continuation of or survival of me. Specifically, she suggests that psychological continuity is enough – it is enough that the later people have the same or nearly the same beliefs, desires, and so on that I have.

I don’t think this is right, but back to the Trinity: In her view, the god which is a God-stage (temporal part of God) called the Father would, just before the Incarnation, be mistaken to think Read More »“Sabellianism Reconsidered” Considered – Part 4