Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

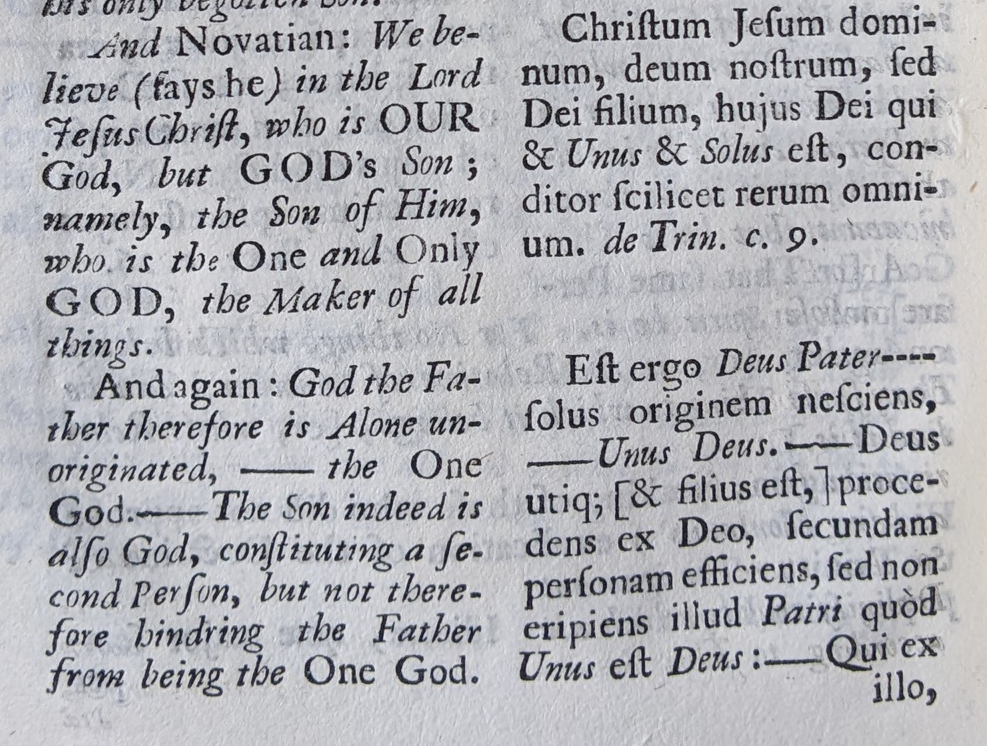

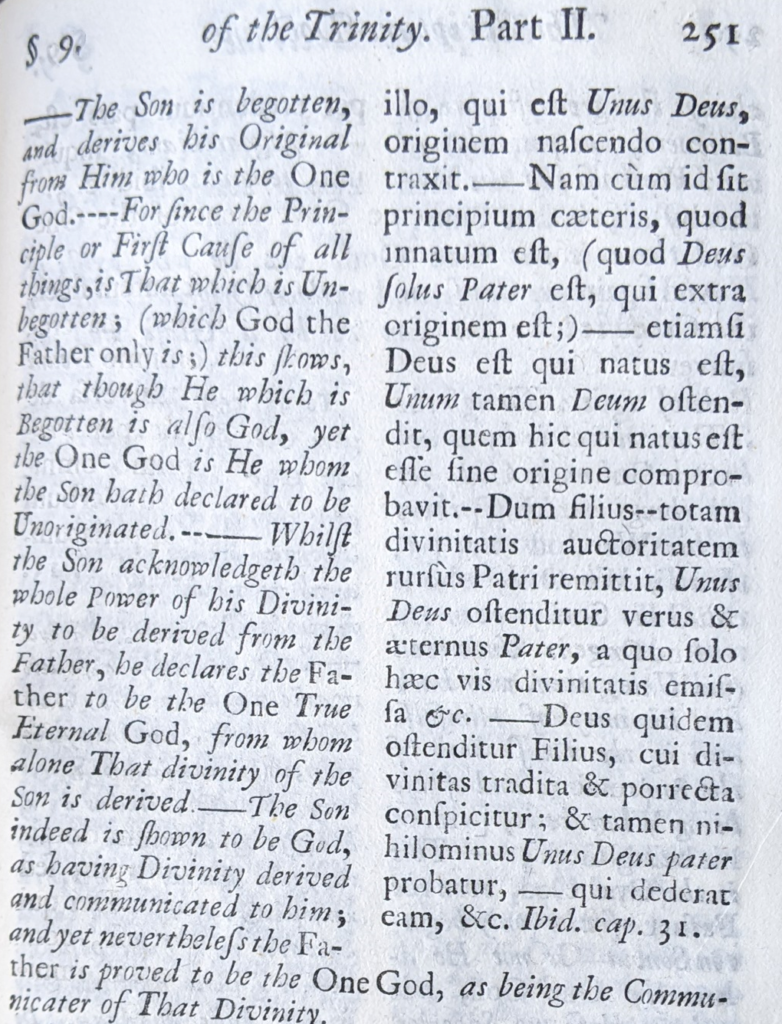

In this second episode (part 1 here) you’ll learn about the very interesting last two chapters of Novatian’s book On the Trinity, chapters which tell us so much about the range of theological opinions in mainstream Christianity in the middle of the 200s.

In chapter 30, he relates three arguments of his opponents, arguments from mainstream Christians who rejected the then-new logos speculations. These are what modern historians call Modalistic Monarchians and Dynamic Monarchians.

My analyses of these arguments are as follows:

The first, “direct” Modalistic Monarchian argument

- There is exactly one god. [That is: there is a god, and anything which is a god just is that aforementioned one.] (premise)

- Christ is a god. (premise)

- [The Father is a god. (premise)]

- Therefore, Christ just is the Father (and vice-versa). (1-3) [In other words: Christ and the Father are numerically one.]

This argument is valid. But, is it sound? Should we accept this argument as sound, or should we deny at least one premise, showing how it is unsound? What would Novatian advise? And what should a trinitarian theologian say about the argument?

The second, “indirect” Modalistic Monarchian argument

- Christ and the Father are numerically distinct. (Assumption to be refuted)

- Christ is a god. (premise)

- The Father is a god. (premise)

- [For any x and any y, and any kind-term F, x and y are the same F only if x just is y (and vice-versa).] [In other words: being the same thing of some king implies being numerically the same.] OR 4. For any x and any y, x and y are the same god only if x and y are numerically identical. (premise)

- Therefore, Christ and the Father are not the same god. (1,4)

- Therefore, there are at least two gods. (2,3,5)

- Therefore, it is false that there is only one god. (6)

- There is only one god. (premise)

- Therefore, it is not the case that Christ and the Father are numerically distinct. (1-8)

- Therefore, Christ just is the Father (and vice-versa). [That is: Christ and the Father are numerically identical.]

Again, the argument seems valid, and so either we must deny at least one premise (showing the argument to be unsound), or accept the conclusion (so that the argument is sound). What should we say? What should a trinitarian say? What does Novatian say?

The third argument comes from a very different brand of “Monarchian” Christians: what historians call the “Dynamic Monarchians,” or in present-day terms, biblical unitarians. These are mainstream Christians who rejected speculations that Christ had “two natures,” human and divine. Instead, they insisted, with Peter, that Jesus is “a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs, which God did among you through him” (Acts 2:22, NIV).

The Dynamic Monarchian argument

- Christ is a god. (Assumption to be refuted)

- The Father is a god. (premise)

- Christ and the Father are numerically distinct. (premise)

- [For any x and any y, and any kind-term F, x and y are the same F only if x just is y (and vice-versa).] [In other words: being the same thing of some king implies being numerically the same.] OR 4. For any x and any y, x and y are the same god only if x and y are numerically identical. (premise)

- Therefore, Christ and the Father are not the same god. (3,4)

- Therefore, there are at least two gods. (1,2,5)

- Therefore, it is false that there is only one god. (6)

- There is only one god. (premise)

- Therefore, it is false that Christ is a god. (1-8)

- Therefore, Christ is not a god. (9)

Again, the argument seems to be valid. What will Novatian do? After all, he seems committed to the truth of each of the four premises (2, 3, 4, 8)! So if the argument really is valid, he will thereby already be committed to the truth of the conclusion, step 10.

In trying to diagnose where these “heretics” go wrong, Novatian discusses what I’ll call:

The Lord/Master/Good argument

- There is only one F – call it a.

- There is some b which is numerically distinct from a, and b is rightly called “F.”

- Therefore, there are at least two Fs.

Novatian’s point is that an argument like this is invalid – that 3 doesn’t follow from 1 and 2. And surely he is right about that. But none of the Monarchian arguments just surveyed seems to rely on any such crude mistake, e.g. on confusing being a god with being called “God” or “a god.” When those arguments mention the claim that “Christ is a god” they mean this in the sense in which logos theorists like Novatian mean it. And clearly, Novatian and company do not mean only to say that the word deus can be applied to Christ!

At the end of the day, Novatian’s responses to these first three Monarchian arguments are clear enough. Moreover, in my view, he is clearly correct about all three of them! Do you agree? Why or why not?

Links for this episode:

Novatian (Papandrea, trans.) On the Trinity, Letters to Cyprian of Carthage, Ethical Treatises

Papandrea, Novatian of Rome and the Culmination of Pre-Nicene Orthodoxy

Novatian (DeSimone, trans.) The Trinity, The Spectacles, Jewish Foods, In Praise of Purity, Letters

podcast 271 – Does your Trinity theory require relative identity?

podcast 224 – Biblical Words for God and for his Son Part 1 – God and “God” in the Bible

podcast 124 – a challenge to “Jesus is God” apologists

podcast 334 – “Who do you say I am?”

God and his Son: the logic of the New Testament

podcast 291 – From one God to two gods to three “Gods” – John 1 and early Christian theologies

Clarke, The Scripture-Doctrine of the Trinity

This week’s thinking music is “initial bridge” by Koi-discovery.

Dale, this got me thinking. Do you think Novatian not wanting to address the “mere man” Christology in the 200s AD, along with a few others who reject what they call the “mere man” Christology are reacting to the early “adoptionists?”

I recall Justin Martyr noting that some followers rejected the virgin conception/birth (perhaps he meant the Ebionites), who instead believed Jesus to be conceived of Mary and Joseph. Have you found any documents or arguments in the early church that suggest that several people rejected Unitarian Christology because it mistakenly got lumped into adoptionist Christology?

Just like many might anachronistically (as you said) call Novatian’s Christology “Arian”, I wonder if some people began to wrongly assume most anyone we would today call “Unitarian” was really an “adoptionist.” I’ve found it difficult to find Ebionite writings, but perhaps they were the ones who came up with the phrase “mere man.”

Your thoughts?

Hi Matt – Novatian does address “mere man” views, aka Dynamic Monarchian views of God and Jesus. It’s just that, somewhat inconveniently for him, he thinks their one argument that he discusses is a sound argument. But of course a logos theorist in general is going to agree with a Dynamic Monarchian that the one God just is the Father, and that Jesus is a numerically distinct and lesser being. We don’t know, I think, who coined “mere man” (psilanthropos). But I suspect it sort of grew out of 2nd c. battles between logos theorists and various gnostics, who agreed that there just must be more to Jesus than just humanity. Did people reject a human-only view of Jesus because they assumed it must be “adoptionist”? Perhaps. But I’m not aware of any direct evidence for that. And one only has to read Luke to get the idea that the man Jesus was always God’s Son, in a sense, because of his miraculous conception. About extant Ebionite writings – I don’t think there are any. We’re dealing only with very thin and hostile reports. But that’s typical for anything but logos theory in 100s-200s. Stuff that was not later deemed consistent with (or pointing to) later orthodoxy just didn’t get copied often enough, it seems.

Comments are closed.