Stephen Prothero, of Boston University, is the rare professor who is to a household name and face. He’s been on all sorts of media, and is an able spokesman for the cause of religious literacy. Preach it!

Stephen Prothero, of Boston University, is the rare professor who is to a household name and face. He’s been on all sorts of media, and is an able spokesman for the cause of religious literacy. Preach it!

His latest book, God is Not One, is possibly the best introduction to a variety of religious traditions for the general reader. It’s well-written, informative, humorous, apt at comparing religions, and I would say pretty fair. I recommend it overall. The book is worth it just for his bashing of the soft-headed pluralism that infects so many popular books on religion. (Ch.1)

Less positively, Prothero’s outlook on religion is colored in many ways by the fact that he is an ex-Christian, having been raised as a mainline church. He sports of whole range of attitudes I see as deriving from this, or from this plus our present intellectual scene. Also, it strikes me that his childhood faith he left behind was just that. In any case, he has a nice way of wearing his inclinations on his sleeve. An author should be opinionated.

Here I want to ask: Is Prothero both fair and accurate in how he presents Christian belief? He says:

…the Christianity… of my childhood… was all about the doctrine of the Incarnation, which to me was as mysterious as adult life in general. According to this core Christian teaching, at the fulcrum of world history God took on the form of a helpless baby, born of a frightened young woman and held in the rough hands of a carpenter. “What if God was one of us?” asks the Joan Osborne pop song. Christianity responds, “He was!” (p. 68)

Well, is.

Again, at one level,

There is the story of Jesus Himself, the God who is born in a manger… and dies on a cross… (p. 72, emphasis added)

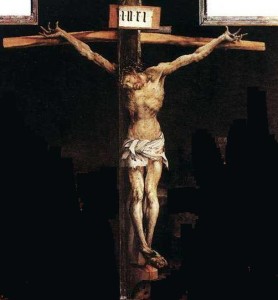

So, “God,” presumably the only God (p. 68), is the man Jesus. The painting above is a portrayal of the day God himself died.

But given that Christianity’s is a “soft” monotheism (pp. 68-9), also

…Christians see God as a mysterious Trinity: there persons in one godhead, or as novelist J.C. Hallman brilliantly put it, “triplets perched on the fence between polytheism and monotheism.” (p. 69, emphasis added)

Prothero dutifully summarizes the Nicene creed on that page, but this discussion may confuse. If Jesus is God, and God is the Trinity, then don’t Christians think that Jesus is the Trinity? Or rather: why don’t they think that?

Given how much Christians care about doctrine (pp. 69-70) it would’ve been better say a bit more about, the fully evolved doctrine of Christ’s two-natures, and perhaps generation and procession, and the catholic view that the pre-human Jesus created the cosmos. Probably more too about why many Christians think that because of the atonement, Jesus must be “fully divine.” These things should get a least a mention, if you’re going to devote a couple of pages to Mormonism in the chapter.

He refers often to mystery, but not to the paradoxical beliefs which have so motivated Christians to employ the tools of philosophy and logic to exorcise apparent contradictions. For example, that the all-knowing God was an ignorant baby, or that an essentially immortal divine person died.

Finally, he’s happy to leave things unclear; but it would be worth pointing out, consistent with his emphasis on the “staggering” diversity in Christianity (p. 66) that some Christians understand the Trinity modalistically – as three ways one divine self lives – and others tritheistically – as three divine selves living in harmony. To others, yes, as an mostly unintelligible mystery – but many thinking Christians are driven to come up with a more articulated view.

To answer my own questions:

- Fair? Yes, I would say fair enough. He’s more concerned to present Christianity at the popular level, than as believed by theorists. Nothing his says me strikes me as a misrepresentation, much less a malicious misrepresentation.

- Accurate? It could be more accurate, I would say. He tends towards the view that too much interest in doctrine, in theological theories, in finely articulated and true religious beliefs, is… twisted, unhealthy, weird, maybe perverse. I see this attitude constantly popping up in the book. As someone who does philosophical theology and philosophy of religion for a living, I of course don’t agree! But I suggest he should correct for this, including at least the ideas noted above.

A few minor corrections: It’s no longer true that most Catholic Bibles do, but most Protestant Bibles don’t have explanatory notes. (p. 80) About his assertion that the Bible nowhere so much contemplates lesbianism (p. 95), that probably needs qualifying, in light of Romans 1. Mentioning “suburban megachurches and their confident sermons about how Jesus would vote” (p. 99) – that is, I think, largely an unfortunate stereotype based on exceptions rather than the rule. In my experience, which yes, includes some evangelical megachurches, pastors tend to be circumspect and generally non-partisan about politics, especially in the pulpit. Such culture-war rhetoric is out of place in the chapter.

Finally, I emphasize that it’s a very good book, packed with information, in world full of crappy books about religion. He loves his subject, and it shows. And he shows a proper sympathy for the traditions, and for the people within them. Reading it is like taking that good class on world religions or comparative religion that you wished you’d taken in college.

The picture at the top of this page has been haunting me – I think in a good way. I have studied it carefully several times, with a growing sense of horror. It doesn’t really matter whether the details are technically accurate; the picture’s impact is huge. So I’d like to accept your invitation to “share”. But what it has meant to me today requires a bit of background.

Recently I came across a letter written July 20, 1989. The letter brought back vivid memories of a time when a good friend stopped on her way from Winnipeg and spent the night with me before going home the next day. We talked about many things that night; but the recurring theme seemed to be the desire, the aching desire to be like our Lord Jesus in his righteousness. Those who hunger and thirst after righteousness will ultimately be filled with what they long for – Jesus said so – but the evidence seems so small.

Next morning after breakfast, my friend told me she had wakened with two words in her mind: “Take, eat.” She didn’t know what it meant, but she couldn’t shake those words from her mind. And now I will quote from her letter:

I won’t continue; but the memory of that feast was still very much on my mind today while we “broke bread” in memory of him. Later, I listened to a tape of music. The first piece was “Panis angelicus.”

I know the first word is “bread”. But the real punch came with the last sentence: “Pauper, pauper …” (the translation “lowly” doesn’t seem to do it justice.)

And then I remembered the picture of the “dead Jesus” at the top of this page. What a perfect representation of total poverty!

“For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, that you through his poverty might be made rich” (2 Corinthians 8:9).

“This is my body, broken (as bread is broken) for you.”

“Take, eat.”

Dale

I briefly ‘skimmed’ your post several weeks ago- and only got to read it properly this morning.

It is full of ‘gems’ and I am amazed that no one has posted a comment on it.

One thing which stood out was your comment that”…many Christians think that because of the atonement, Jesus must be fully divine”

I am continually being assailed by this view- and I generally respond that mainline Christians seem to have created the doctrine of the trinity merely to support their view of the atonement!

The “Moral Improvement’ theory of Atonement makes agreat deal more sense to me than the alternatives- of course the evangelicals will argue ‘to the death’ against this.

As a matter of interest I live in a country where powerful individuals harbouring evil genocidal and tribalistic impulses, claim to be Christians – and conveniently hold to the misguided view of ‘perpetual salvation’.

Martin Luther seems to have initiated this view in his ‘sin boldly’ letter – but it can lead seriously evil people to ‘carry on doing what they wanted to do’!!

To be forgiven there must be some repentance- and some ‘works’ would be nice too!!!

I am told that the real fear of the Catholic Church at the time of the Reformation, was that Protestants would become Unitarian.

Luther seems to have realised that the mantra ‘Christ= God’ was needed to create a worldwide church (as it is said to have done a millenium earlier) and , in spite of the fact that he struggled to comprehend the doctrine of the trinity , he became one of its strongest ‘enforcers’.

It’s all a sad reflection of our human nature!

Really looking forward to your next post.!!

Perhaps you could address the ‘pre-existence’ issue in a future paper?

Very best wishes

John

Comments are closed.