Here are a few observations on my co-blogger Dr. Scott Williams‘s recently published article in the Journal of Analytic Theology, called “Indexicals and the Trinity: Two Non-Social Models.”

Here are a few observations on my co-blogger Dr. Scott Williams‘s recently published article in the Journal of Analytic Theology, called “Indexicals and the Trinity: Two Non-Social Models.”

There’s a lot going on in the piece – some terminology, some history of theology, and some interesting dialectic with one of the best philosophers working on this topic, Brian Leftow, which centers around the concept of an “indexical” term.

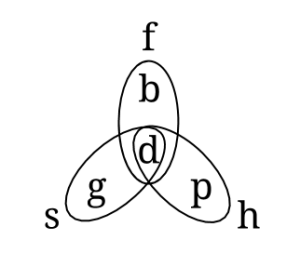

But in this post, I want to narrowly focus on the theory which Dr. Williams suggests to us. This comes in his section 4, pp. 84-8. He calls it “soft LT” (to contrast it with Leftow’s “hard LT”) and I would expound it with the chart here, which I made.

f, s, and h are, respectively the divine persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. d is the divine nature which they share, and which is one component in each of them. The other component in each is some “incommunicable personal attribute” (p. 84), respectively: begetting (b), being begotten (g), and being spirated (p). The ovals show the two parts or components of each divine person. (I take it that the model is committed to denying any classic doctrine of “divine simplicity.”)

None of f, s, h is identical to the divine nature, but each is “numerically the same things as” d, without being strictly identical to d. d is a universal – a shareable property/attribute/nature. But it is also, I take it, a concrete thing. (pp. 84) It, but none of the persons, exists a se – that is, independently of anything else. But that won’t be true of any of f, s, or h, or, I believe, of g or p or d. Why? Because these things exist, ultimately, because of d. They would not exist if d did not exist (note, of course, that this is a counterpossible – it is assumed to be broadly logically impossible that d exists. Or more simply: they all exist, in part, because of d).

Finally, there are timeless, causal relations between the persons. (These are not in the above chart.) f causes d to be shared with s, and f & s together cause d to be shared with h.

There’s more that can be said by way of exposition, and perhaps Scott will grace us with some more in comments (or posts).

Here are three objections (or rather, two questions and an objection) which occur to me:

- Is there a triune god here? If so, which thing is it? Is it the sum of all the objects shown, or f+s+h+d, or what exactly? (It can’t be d, because it’s not a god, and isn’t tripersonal.)

- Second, the only thing which exists a se here is d. But only the one God exists a se. But d is not the one God (but rather a component of him?) Ergo, the theory is false. How to answer this?

- Why should the three divine persons here, which are asserted to be not identical (because they differ), be counted as “numerically the same thing as the divine nature”? (p. 85)

Pingback: podcast episode 10 – interview Dr. Scott Williams on “Latin” Trinity Theories » trinities

Thanks, Joseph, for this interesting dialogue. I hope you have a great conference. I think there’s a lot of substance here – I want to put the best bits into a post, or maybe more than one. Will try to do it next week, after we’re all done with this 4th of July thing & weekend.

And even more …

Thank you for the kind words Dale!

But if aseity means existing & having one’s perfections not because of any other, then neither deity, in the scenario, can be a se, because each will have this (alleged) perfection of actually being in a certain sort of loving relationship, because of the other.

*I think there’s a third option: the divine persons can’t exist without each other and they exist because of the others, perhaps each is individuated, that is, each is the divine person he is at least partly because of the causal relations he bears to the others.

We may just have to agree to disagree about which are perfections, as you say.

But here’s a new worry. This perfection you have in mind – it is essential to what has it, no? And nothing can exist without having its essential features. Well, doesn’t it follow that A exists because of B, and that also B exists because of A? Doesn’t that seem impossible?

*Not to me. There are many kinds of explanation. We typically think of causal explanation. But it’s not the only kind. It may be impossible that A directly causes B to exist and B directly causes A to exist. But that’s not what we have here with the divine persons. Think of the natural numbers. Perhaps each is the number it is partly because of its place in the series, which involves the successor relation. Or think of spatial points or temporal instants. Perhaps each is the point or instant it is partly because of its place in the series, which involves spatial or temporal relations. I am willing to say the Father is the ultimate cause. Perhaps there’s a sense of ‘aseity’ in which the Father has aseity and the others don’t. But I don’t think of such aseity as great-making and so I don’t think it makes the Father greater.

Must go to the airport now!

Best,

Joseph

More…

But here we’re not properly talking Christian doctrine – either something believed or confessed by mainstream Christianity – but really, competing rational reconstructions of such. There’s no simple way to compare this. But it is a significant “cost” of a theory if it requires us to revise what seems heretofore to be self-evident truths of metaphysics or logic.

*I think I disagree here. The doctrine of the Trinity is believed and confessed by mainstream Christians. I think most Christians believe that the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are three persons, that each of them is God, and that there is only one God. They might say ‘I don’t understand how that works, but I believe all those claims’. The sortal relativity of identity thesis says that some x and y are the same R but different Ss. My idea is that these claims clearly imply the sortal relativity of identity thesis, and that most Christians implicitly accept an instance of the thesis. This is how I imagine an ideal question-answer dialogue going:

Q: How many persons are the Father, the Son, and the Spirit?

A: They are three persons.

Q: Are they the same person or are they different persons?

A: They are different persons.

Q: Is each person God?

A: Yes, each is God.

Q: Are they the same God or are they different Gods?

A: They are the same God.

Q: So the Father, Son, and Spirit are the same God but different persons.

A: Yes, that’s right.

I don’t think we have competing rational reconstructions going on here. Most Christians believe what they are told the Church believes or what scripture teaches. And most are told the Church believes the doctrine of the Trinity or that scripture teaches this. I think this point holds even of most Christians today. But it certainly holds of most Christians who have lived thus far. I agree that it is a cost of a theory that it conflicts with what seems self-evident. But I’m not sure we are in the area of theory here. This is more like basic belief by way of testimony.

Hi Dale,

I’m off to a conference in England tomorrow. So I’m not sure when if at all, I’ll be able to get to your other points. But here’s a first installment. Again, answers after the asterisk.

Joseph, if you’re right, then Rea would have an answer to my first objection in my paper. So your idea is that each of the Three counts as a triune God, by my definition. Take the Father. He doesn’t in any sense contain, and isn’t composed of the other persons. But my definition allows that a triune God “is” three persons. So, the Father is (strictly identical to) himself. And he “is” (numerically the same as but strictly non-identical to) both Son and Spirit. I think – and maybe I should say this somehow in my definition – that each person needs to “be” God in the same sense.

*This not precisely what I had in mind. But it was close! Each person is God in the same sense: each person is the same God as someone. And the Father is the same God as the Father (and the Son and the Spirit). And the same is true of the Son: he is the same God as the Father (and the Son and the Spirit). And the same holds of the Spirit.

I think my point still sticks. On Rea’s CT, the Father is a GOD, and shares something like a matter with two other GODs. But that doesn’t make him, or them, a triune God.

*Of course, Brea would reject this description: they would never allow that the Father bears a relation to two other Gods, because we only ever count Gods by the relation same God. So there aren’t two Gods to which the Father bears any relation. Why must we count Gods like that? That’s just how, on the theory, the concept of God works. My original point was that I don’t see why to be orthodox we need to say that some God is triune. I still think that. Only later on did I ask for a definition of ‘triune God’. Here’s a dilemma. Either you give me a definition where on CT there is no triune God and I say ‘why think we need one of those?’ or else you give me a definition where on CT there is a triune God and I say ‘there you go!’

Another angle: an important part of my definition is that the persons are “equally divine”. I left this out in the comments just now – sorry. But see the “official” version: https://trinities.org/blog/archives/3747

Go back then to the Rea-type theory. In contrast to many trinitarians, he wants to take into account the “I believe in one God, the Father…” parts of the creeds. I don’t think he says this in his papers, but he might try out this move: the Father “is God” in the sense that he’s identical to the one God. Not so, with the other two – they share a nature with the Father, which makes them “numerically the same” God as him. And so all three “are God” – but not in the same sense. I would say, then, that not being equally divine, there is not really a triune God on this theory.

*That seems like a good reason for Brea not to try that move. We should say that each person is God in the same sense and each is equally divine.

Brea? LOL

If you publish something on the one divine person must generate two others argument, we could call that the Jedburne theory. 😛 I for one would prefer that to Swinwab. Although “Jedburne” sounds like it could be a Star-Wars themed NASCAR racing team, or a speed metal band from Kentucky. 🙂

Good points here. Let’s pursue this a bit. (Again – post? You have way too many, and too deep of thoughts for mere comments, Joseph. Want to persue this in a post?) So, assume the existence of one divine person. This person must be perfect. But he may have a perfection which rules out aseity. Say, following Richard of St. Victor, you say that a perfection is actually enjoying a sort of love with a peer or near-peer. This God, then, must (eternally or timelessly) cause such a partner to exist, to love.

Does this rule out aseity? It may depend what is meant. If it is just, existing & not because of another, then no, it doesn’t rule out aseity. Then, the first deity will have a perfection that the second doesn’t have, and will, prima facie, be greater. Still, this second might be a near-peer.

But if aseity means existing & having one’s perfections not because of any other, then neither deity, in the scenario, can be a se, because each will have this (alleged) perfection of actually being in a certain sort of loving relationship, because of the other.

We may just have to agree to disagree about which are perfections, as you say.

But here’s a new worry. This perfection you have in mind – it is essential to what has it, no? And nothing can exist without having its essential features. Well, doesn’t it follow that A exists because of B, and that also B exists because of A? Doesn’t that seem impossible?

A would of course be the whole and only sufficient cause of B. But something B does, supplies a necessary condition of A’s existing. And A also does that for B. So if something’s action is or implies conditions necessary for the existence of some thing, then it exists (in part) because of it (the thing doing the action).

So A exists because of B, and B exists because of A. This strikes me as obviously impossible, if we were talking about being the sole efficient cause of.

Here, A can’t exist without B. And B can’t exist without A. So if either exists, both must exist. But I still smell an impossibility. Here’s an analogy – that something causes itself to exist, i.e. brings itself into existence in time. So at t1, it doesn’t exist. And at that time, it exercises its power to bring itself about, so that at t2, it exists. This is manifestly impossible – what doesn’t exist at a time, doesn’t have any powers to exercise at that time.

Let’s try to take time out of it. A is “logically” prior to B, and must be, if it is the source of B. But at that same point – not in time, but in logical order, if I may put it that way – B must “already” exist, so that A can exist at all. This strikes me as impossible – doesn’t it you? I admit, this is not an airtight proof, but I think it is a problem that a Swinburne-type position on perfection must address.

Another angle: suppose we think there must be a ultimate source of all else. This, we want to say, is A. But A exists only because B does (and vice versa). So, there is no ultimate source. And if there must be one, then this scheme is impossible, right?

“I believe that Christian doctrine can teach us some metaphysics.”

In principle, yes, why not? But here we’re not properly talking Christian doctrine – either something believed or confessed by mainstream Christianity – but really, competing rational reconstructions of such. There’s no simple way to compare this. But it is a significant “cost” of a theory if it requires us to revise what seems heretofore to be self-evident truths of metaphysics or logic.

Look, you could get rid of some problems by simply affirming that contraditions can be true, or by asserting that the Ind of Id is false. But you wouldn’t do that, and rights so.

Perhaps your idea is that the Athanasian creed must be read as making claims of relative identity (which can’t be understood in terms of strict identity). But only uber-intellectuals have thought that. Perhaps Geach was the first. Or perhaps Abelard. But we can’t say that the community as such affirmed relative identity, right?

Joseph, if you’re right, then Rea would have an answer to my first objection in my paper. So your idea is that each of the Three counts as a triune God, by my definition. Take the Father. He doesn’t in any sense contain, and isn’t composed of the other persons. But my definition allows that a triune God “is” three persons. So, the Father is (strictly identical to) himself. And he “is” (numerically the same as but strictly non-identical to) both Son and Spirit. I think – and maybe I should say this somehow in my definition – that each person needs to “be” God in the same sense. This is so, for many trinitarian theories. If we don’t say something like that, then unitarian theories will count. Take a Clarkean theory. God = the Father. The Son too “is God” (but is not identical to God) because he is divine, because of his mysterious eternal generation by God. Similarly, the Holy Spirit, on this theory, “is” God (in a manner like the Son “is” – not like the Father is (=).) Or take just an imaginary, crude “Arian” theory. Before creating the cosmos, God creates Son and Spirit. The Father = God. But Son and Spirit “are God” in that they came to be from his substance, or were created ex nihilo by him. But these are not trinitarian views.

I think my point still sticks. On Rea’s CT, the Father is a GOD, and shares something like a matter with two other GODs. But that doesn’t make him, or them, a triune God.

Another angle: an important part of my definition is that the persons are “equally divine”. I left this out in the comments just now – sorry. But see the “official” version: https://trinities.org/blog/archives/3747

Go back then to the Rea-type theory. In constrast to many trinitarians, he wants to take into accound the “I believe in one God, the Father…” parts of the creeds. I don’t think he says this in his papers, but he might try out this move: the Father “is God” in the sense that he’s identical to the one God. Not so, with the other two – they share a nature with the Father, which makes them “numerically the same” God as him. And so all three “are God” – but not in the sense. I would say, then, that not being equally divine, there is not really a triune God on this theory.

Hi Dale,

My answers follow asterisks:

1. [A triune god] is a god, and more specifically a perfect being, who “is”, somehow contains, or is composed of three equally divine “persons”. (Note that these ambiguities and disjunctions are on purpose – I’m trying to capture the widely acknowledged concept of a triune God, as opposed to a “unipersonal” or unitarian God.)

*Good. Well, like I said (1st post, 1st point), we can accommodate that like this. The Father is a god (or a God or God). He is the same God as himself and the same God as every other divine person. So each divine person can count, on your definition, as a triune God. But each is the same God. So there is only one triune God.

2. “But since we only count gods by the relation of being the same god.”

Sure. But we should understand that to imply identity, aka being the same thing as. I agree with Rea that the relative identity theorist needs to motivate his relative identity claims – it can’t only by that orthodoxy requires it, as that seems to be special pleading. Rea, in my view, does address this – though his proposal is in the end very problematic.

*I disagree. I am assuming that if we count gods by same God, we are not counting by identity. I am assuming that x is the same R as y doesn’t reduce to x is the same as y and x is an R. I believe that Christian doctrine can teach us some metaphysics. If we learn that the Father and the Son are the same God but different divine persons, then we can come to know on that basis that the sortal relativity of identity claim is true: that it could be that x and y are the same R but different Ss. I don’t see any need to have a non-theological precedent for this. I wouldn’t apply sortal relativity of identity to the problem of material constitution. But I’m happy enough for someone who already believes in the thesis from their analysis of Christian doctrine to apply it to non-theological cases.

3. “I guess I’m not so sure that perfection requires aseity in a situation like this.”

I don’t see how it would be situation-relative; I think you must deny outright that aseity isa perfection. That seems like a significant theological cost to me.

*Sorry, I didn’t intend to imply that whether perfection requires aseity is somehow situation relative. But I don’t see why I must deny that aseity is a perfection. Perfect being theology needn’t say that every perfect being has every perfection. Some perfections may be incompatible with each other. What perfect being theology requires is that some perfect being has a best possible package of perfections. There can be trade-offs though. It might be that aseity is a perfection but is incompatible with perfect inter-personal love that includes sharing and co-operating in sharing among equals. But I’m willing to allow that reasonable folk may disagree about what the best package of perfections is here.

4. “Some believe in transferable tropes.”

Do you mean, like, people who reduce substances to related groups of tropes? Or who?

*Those who believe in transferable tropes: D.C. Williams and Keith Campbell. But it’s true. I don’t know of anyone who believes in transferable tropes but doesn’t reduce ordinary particulars to bundles of compresent tropes. But there are certainly believers in tropes that don’t reduce ordinary particulars to bundles: C.B. Martin, John Heil, and E.J. Lowe. Perhaps the medievals think that tropes transfer and they certainly don’t reduce ordinary particulars to bundles of tropes. For example, perhaps for them, fire, which is actually hot, causes water that is potentially hot to become actually hot by way of the transfer of an individual form of heat from the fire to the water.

5. “Why think a trope can’t be shared?”

I assume that we can’t reduce substances to somehow related sets of individual properties. But then, an individual property will just be a substance existing in a certain way, a mode if you will. And I have a very strong intuition that such can’t be shared. I talk about this in my recent, about to come out paper on Hasker’s ST.

*Are you thinking of tropes as such here? Or are you saying that though there may be such a thing as Socrates’ wisdom, it’s not really a trope? In any case, I take it your argument here is that it seems to me on reflection that a trope can’t be shared, and I can’t think of a good reason why they can be shared, so, on this basis, I believe they can’t. That’s fine. I can even go along with the first premise, but in that case I will question the second premise.

6. “different divine persons do share the divine nature. But different gods can’t.”

I think more needs saying here, on what a god is, if not a divine person. Being a (literal) god in the Bible always involves being a self.

*Great point! In my dissertation, I called this the conceptual problem. How do the concepts of a God and a divine person differ? My answer is that the concept of a God is that of a divine substance or being, but that of a divine person is just that of a divine person. Since the concept of a substance or being differs from that of a person, the concepts of a God and of a divine person also differ. I agree that any God is a self.

7. Joseph, if you would like to float some ideas here, e.g. a rel. id model of the Trinity which differs from Rea’s, we would love to get some posts from you.

*I’m not sure I have anything different to offer than what van Inwagen and Brea (think Brangelina!) already offer.

Best wishes,

Joseph

Jim,

For a good analysis of John 17:5 see

http://www.angelfire.com/space/thegospeltruth/trinity.html.

Best Wishes

Abel

Hi Dale,

Dale said, “I note that unitarian theories preserve the I-thou Father-Son (God-Son of God) relationship, without threatening monotheism.”

I have major reservations about unitarian theories presenting a plausible interpretation of the “I-you” relationship of the Son and Father in John 17:5. But I will carefully read any respective well-written unitarian interpretation.

Peace,

Jim

I have a historical question for anybody who knows the answer. Did Augustine or any other Latin church father *really* say that there is no “I-you” psychological phenomena in the Trinity? I recall Augustine’s Trinitarian analogies that could suggest such a statement, but did Augustine *clearly* state Non-social Trinitarianism?

Peace,

Jim

” My suspicion is that this is Dale’s line of argumentation, or something approximating it when he says that only God is “a se.” ”

I think this is implied by being a perfect being. Don’t you?

I don’t know that Arius argued that (I don’t remember); I think it was Eunomius who asserted that something like that was God’s essence. (He was then hammered for daring to say we could understand God’s essence.) I don’t claim that; but I do think, based on the Bible, and on perfect being reasoning, that we can understand some features to be essential to God, i.e. we can to some degree understand “part of” God’s essence. I think nearly all analytic Christian philosophers would agree. This camp is, happily, a bastion of monotheism, as opposed to believe in some indescribable “Ultimate”. (Work in progress: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFzObFaF2b0 – I’m hemming and hawing about some of the terminology and other points, but I think the contrast of monotheism and Ultimism is solid and important.)

“definitely look at JT Paasch’s book on internal divine production”

I need to do that, thanks. I’m not sure how the “internal” would make a difference – what is internally produced, is produced.

“creature, including all its constituents are created from nothing. But, the Son is not created from nothing. Rather, the Son is “from the substance of the Father,” that is, the Son’s divine nature is communicated to him”

In my view, some unitarian theories are consistent with that. It’s interesting how “creature” became a term of art, defined as you say here. My memory is that 2nd and 3rd c. catholics did sometimes call the Son (even pre-existence and in some sense divine) a creature (or some related terms).

“Tell me what a triune God is and I’ll tell you whether I think there is one. ”

It is a god, and more specifically a perfect being, who “is”, somehow contains, or is composed of three equally divine “persons”. (Note that these ambiguities and disjunctions are on purpose – I’m trying to capture the widely acknowledged concept of a triune God, as opposed to a “unipersonal” or unitarian God.)

“But since we only count gods by the relation of being the same god”

Sure. But we should understand that to imply identity, aka being the same thing as. I agree with Rea that the relative identity theorist needs to motivate his relative identity claims – it can’t only by that orthodoxy requires it, as that seems to be special pleading. Rea, in my view, does address this – though his proposal is in the end very problematic.

“the paraphrase is consistent with there being no gods” That’s right. I was being sloppy. It must have a clause asserting that there’s at least one god.

” I guess I’m not so sure that perfection requires aseity in a situation like this”

I don’t see how it would be situation-relative; I think you must deny outright that aseity isa perfection. That seems like a significant theological cost to me.

“Some believe in transferable tropes”

Do you mean, like, people who reduce substances to related groups of tropes? Or who?

“We know it plays a certain role”

Do we? Seriously, we must be careful in working backwards like this. Sometimes, we must go back and question the assumptions that generate the puzzle. Metaphysics is what we philosophers are trained in, but it’s not the only tool needed.

“Why think a trope can’t be shared?”

I assume that we can’t reduce substances to somehow related sets of individual properties. But then, an individual property will just be a substance existing in a certain way, a mode if you will. And I have a very strong intuition that such can’t be shared. I talk about this in my recent, about to come out paper on Hasker’s ST.

I guess I can see why you might think a trope can be shared, if your ontology has only tropes but not things, or things which are reducible to tropes… But I need to think more about the possibilities you bring up here.

“different divine persons do share the divine nature. But different gods can’t.”

I think more needs saying here, on what a god is, if not a divine person. Being a (literal) god in the Bible always involves being a self.

Joseph, if you would like to float some ideas here, e.g. a rel. id model of the Trinity which differs from Rea’s, we would love to get some posts from you.

Along the lines of Jim’s comments,

“since this is a non-social view there is no “I-you” psychological phenomena between divine persons”

This seems a big biblical liability of the view. Consider the central themes in the gospels that Father loves and sends the Son, and that the Son loves and obeys the Father. Or just the fact that Jesus prays to God, privately and publicly.

I note that unitarian theories preserve the I-thou Father-Son (God-Son of God) relationship, without threatening monotheism.

Hi Scott,

If I may, I wish to narrow my question to discussion of one biblical verse, Luke 10:21, which I understand is outside the direct focus of this essay. But I raise the question because the question is completely fair in general discussion of *non-social* Trinitarianism.

Here is Luke 10:21 (NRSV):

At that same hour Jesus rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said, “I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants; yes, Father, for such was your gracious will.”

When somebody says that there is no “I-you” psychological phenomena in the Trinity, I can barely think past the Son saying “I thank you, Father.” Regardless of excellence in your essay, I need to know what you suppose Jesus meant with his “I-you” praise to the Father. In a nutshell, this is my face value objection to non-social views of the Trinity.

Peace,

Jim

Hi Scott,

Per comment 6:

Yes, the term “non-social” implies a lot. I understand rejecting social views that divide the divine substance while inadvertently or purposely asserting trithesim.

That said, I’ll focus on the relationship of the Father and Son in the Gospels. The Father said, “This is my beloved Son.” The Father revealed things to the Son. And Jesus on numerous times prayed to the Father apart from modeling the Lord’s prayer.

How does a non-social view of the Trinity interpret the *dialogue* between the Father and Son in the Gospels?

Peace,

Jim

Joseph,

RE 3: See page 89 of my article: “If pushed, Richard’s metaphysical account of a divine person might be expressed in contemporary language by saying that the divine nature is a communicable trope and the distinguishing personal attributes are incommunicable tropes.” I take this to be a standard line for any good constitutional model of the Trinity.

RE “aseity”: I didn’t discuss this in the article precisely because a lot can be said about it and my piece was already long enough. When I consider this issue I often think of Athanasius vs. Arius. One reading of Arius is to say that the mark of being God is being unproduced (or, uncreated). So, only God is unproduced. But, the Son is produced. Therefore, the Son is not God My suspicion is that this is Dale’s line of argumentation, or something approximating it when he says that only God is “a se.” Maybe I’m wrong? For coverage of this, definitely look at JT Paasch’s book on internal divine production. “Soft LT” makes the move that Lombard, Henry, and Scotus make: the Son (and Holy Spirit) aren’t creatures, for, a creature, including all its constituents are created from nothing. But, the Son is not created from nothing. Rather, the Son is “from the substance of the Father,” that is, the Son’s divine nature is communicated to him. The Father shares his own divine nature (a communicable trope) with the Son. The Son’s very own divine nature is not “created from nothing.” This is hardly a new position that I’m putting forward. What’s new with “soft LT” has to do with conjoining this model with my take on indexicals. I’ve yet to find any scholastic discussing the issue of indexicals–it has baffled me why they didn’t.

Cheers,

Scott

Hi Dale,

Here’s the rest.

RE 2: I don’t know quite what to say about aseity at the moment. Each divine person does seem to depend for its existence on some entity outside of it: e.g. the Father can’t exist without g or p. I guess I’m not so sure that perfection requires aseity in a situation like this, where the divine persons all must exist and some divine persons essentially actively cause the others.

RE 3: I’ve not said what the divine nature is. We know it plays a certain role: it is that in virtue of which a divine person is God and it is that by sharing which different divine persons are the same God. But as to what occupies the role, I’ve not said. You assume the divine nature is a feature: that’s plausible. You consider two options: it’s a trope or it’s a universal. I don’t know that those are the only options. Why think a trope can’t be shared? Some believe in transferable tropes and if tropes transfer, they can be shared. Moreover, if there are tropes, I’d think some wholes share some tropes with some of their parts. If either claim is right, and if tropes are not universals, then a feature can be shared but not be a universal.

Finally, again, assume identity exists. The Father and the Son are not identical. Identity is a species of numerical sameness. So the Father and the Son are numerically different. And they share the divine nature. So numerically different things can share the divine nature. Indeed, different divine persons do share the divine nature. But different gods can’t. That, right or wrong, is the account of what it is to be the same God that is on the table.

Hi Dale,

I’ll answer the first points first. I wasn’t always sure to whom they were directed. But I’ll just pretend to be Scott or Mike Rea for the time being. I should note I am now much more sympathetic to a relative identity approach than I was.

RE 1: Yes and no. Yes: I am saying ‘Trinity’ is a term that collectively refers to the Father, Son, and Spirit. No: I am not saying ‘God’ or ‘the one God’ is a plural referring term. Tell me what a triune God is and I’ll tell you whether I think there is one.

There is only one god. Is it true to say that there are non-identical gods? Perhaps. Let’s suppose there is such a thing as identity. Then if to say ‘there are non-identical gods’ means no more than this: for some x and y, x is a god, y is a god, and ~x=y, then sure. But since we only count gods by the relation of being the same god and counting by that relation there is only one god, to say there are non-identical gods misleads. It has a false conversational implicature.

I didn’t really give a definition of ‘monotheism’. I’d say its definition is this: monotheism is the view that there is only one God. In logic, how do we understand this? Well, the standard way is to say: something is God and is the same as anything that is God. This counts by identity. If, though, we only count Gods by the relation of being the same God, then the standard way is wrong and we should say instead, as I did before: something is God and is the same God as anything that is God.

I don’t think I understand the charge that the formalization amounts to a gerrymandered re-definition of ‘monotheism’. The formalization should be acceptable even to someone who thinks we only count by identity. If anything, it only suffers from redundancy.

On Rea’s behalf, I reject the proposed paraphrase that to say there is only one god is to say that for any x and y, if x is a god and y is a god, then x and y share the same nature. I assume we are talking here about the divine nature and also that we are talking about something like an individual not a common nature. Here’s why I reject the paraphrase. 1. It gets the truth-conditions wrong: the paraphrase is consistent with there being no gods. 2. I take it Rea is not providing an analysis here but an account. But any paraphrase should preserve meaning. The account here need not preserve meaning.

I hope to get to the other points later.

Best,

Joseph

Hi James,

I suspect that you mean something in particular by the term “interpersonal”? Can you say what that might be? Clearly, since this is a non-social view there is no “I-you” psychological phenomena between divine persons. I take this to be a mark of social views. I assume you’ve read the entire paper?

-Scott

Hi Scott, In your soft Latin Trinitarianism, How do you describe the *interpersonal* relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? Peace, Jim

Sorry for the delay – I have company in town.

Scott and Joseph – thanks so much for the comments.

1. If I understand you, you’re saying that “Trinity” and I guess also, “the one God” are plural referring terms, referring to the plurality of f, s, and h. This seems to me not really trinitarian; on the theory, there is no triune god, though there are non-identical gods, which, as Rea would say, “are to be counted as one.”

About your definition of monothesim – that’s what I consider the gerrymandered Rea redefinition of monotheism. Monotheism is the claim that there’s exactly one god. Rea’s definition can, I think not unfairly, be paraphrased like this: whatever gods there are, share a nature.

“If one is committed to monotheism whether from some metaphysical argument or from divine revelation, then one should say that there’s just one divine essence or nature”. Note the slide here from god to divine essence or divine nature. If the latter mean just divine entity, then no problem. But if they’re shareable properties, it’s not at all clear that’s sufficient for monothesim.

2. Joseph – yes, surely aseity requires being uncaused, and also, it would seem, not dependent on any component. But doesn’t this theory have all three persons existing, in part, because of d? If so, then either none of them is perfect, or perfection doesn’t require aseity. (It seems to me that it does, though.) Scott, perhaps the account needs developing on this score.

3. I was asking about the motivation for the relative identity claims, not for saying there are exactly three. I understand the motivation in the case of Rea (he thinks there is a constitution relation, and in the case of material objects, thinks there is a plausible cause of num sam without id). It seems that for the former question, we need more than that orthodoxy would require it. Look at the model: d is one thing. f is another. d is one component or in some sense part of f. f exists because of d, but not vice versa. f gives d to s, or causes s to have d – but d does not do this. If we’re now told that they’re numerically the same thing… well, they just seem like two things, interestingly related, of course.

Joseph, I take it that the persons can’t be “numerically the same God as d”, because d isn’t a god (but each person is).

Joseph, you say: “any two things that have the same divine nature are numerically the same God” – if a “divine nature” here is a thing like a trope, a indidual property, this is plausible – that would seem to imply that the sharers really are one god (which implies their being =). But the theory requires d to be shared – so it would seem like other universals. Why then, can’t numerically different things have (and share) it?

I might be delayed in responding again, but I well get back to you if you reply.

A suggestion: have a look at Richard Cross’s chapter, “Philosophy and the Trinity,” in the Oxford Handbook of Medieval Philosophy. In it he discusses numerical sameness without identity as it’s used by folk like Henry of Ghent and Duns Scotus. (Aside: Richard wrote this article while I was working on my dissertation; at that time I tried to persuade him – and maybe succeeded- that Henry is committed to the notion of numerical sameness without identity— which I’ve argued for in my article, “Henry of Ghent on Real Relations and the Trinity: The Case for Numerical Sameness Without Identity.”) “Soft LT,” to an extent, is the view espoused by Duns Scotus, which Cross discusses in this piece. But, “soft LT” goes further because it endorses a certain view about indexical (and ambiguous) tokens of thought.

Thanks Dale (for the press!).

Briefly:

1. The name Trinity refers to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. See page 85, last sentence of 3rd paragraph.

2. In the piece I make no claim about “aseity.” Perhaps you inferred from my claim that the divine nature is not itself the end term of a production, to the claim that it is “a se”? I don’t discuss “aseity” because that is another (albeit proximate) issue.

3. Why suppose that the persons are “essentially numerically the same thing as the divine nature without being identical to the divine nature”? (You wrote “things” instead of “thing”.) If one is committed to monotheism whether from some metaphysical argument or from divine revelation, then one should say that there’s just one divine essence or nature. It’s numerically one thing. And, if one is committed to saying that the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, then you need to deny that the “is” in such claims is identity, and deny that it’s the “is” of predication if saying it’s a predicate implies saying that the persons are numerically distinct instances of a generic (abstract) nature. What gets you numerical sameness without identity? Well, that’s just it: numerical sameness without identity. But maybe your question has to do with each person’s being _essentially_ numerically the same thing as the divine nature without being identical to it? At this point I could either try to give an argument for why there are only three divine persons, or say that given the catholic faith, I believe that there are only three divine persons. I’ll opt for the latter sort of response. (I could rehearse other theologians’ argument for why there are exactly three persons, but I don’t want someone to think that such arguments are required for one to hold to “non-social, constitutional, Trinitarianism” (or, “soft LT”).

Hi Dale,

Been a long long time … Hope you are well.

I haven’t yet read Scott’s piece. It sounds really good. Scott’s theory also sounds a lot like Brower and Rea’s theory.

Here’s how I’d answer the questions/objections. If only Scott were around so we could ask him!

1. There is only one God: something is God and is the same God as anything that is God. The Trinity is the plurality of the divine persons, as the Holy Family is the plurality of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus. But to be orthodox we don’t need to say that there is an entity that is both God and triune. Though interestingly the 4th Lateran Council does say that there is a reality that is the Father, Son, and Spirit, but neither begets, nor is begotten, nor proceeds. I wonder if the theory can accommodate this latter claim. Perhaps we might say that each divine person is triune in the sense that each is the same God as every divine person, of which there are three such.

2. Is that something Scott says: that only d is a se? Does he say all else exists *because* d does? That sounds like the wrong thing to say. I know of accounts of ontological independence which would imply that each divine person is ontologically independent, but d isn’t, assuming that d wouldn’t exist if each or all of b, g, and p didn’t exist. It depends what we build into the idea of a se. If being a se rules out being caused, then I suppose the Son and Spirit are not a se.

3. Is your question: why think non-identicals can be numerically the same anything? Or is your question: why think the divine persons are numerically the same God as d? Granted for argument’s sake, the divine persons are numerically the same God as each other because they share the divine nature. Why does it follow each is numerically the same God as d? On the last question, perhaps the idea is that each quasi-hylomorphic compound is numerically the same something as what functions as matter in it. The divine nature trivially has the divine nature, in the sense of just being the divine nature. And any two things that have the same divine nature are numerically the same God. But if you’re right that d is not supposed to be God, then it can’t be the same God as anything, else it would be God.

Perhaps Scott will weigh in and say I’m all wrong and I should just go read the paper!

Best,

Joseph

Comments are closed.