How the three are tightly functionally unified, in Swinburne’s view.

(See below for the interpretation.)

Last time we looked at Swinbure’s suggested reading of the creeds. They can’t he says, be charitably read as holding that in the same sense there’s only one divinity, and that there’s three. Swinburne comes down on the side of three. Like all social trinitarians, he’s attracted to a vision of the Trinity as being a loving community, three eternal and perfect, spirits, three selves, enjoying one another’s company, living in communion with one another, and working together in all they do. In short, he wants to say there are personal relationships internal to God – and this implies that there are persons – subjects of experience, thought, and action – in God. Further, like many readers of the New Testament, he realizes that we need a theory that makes it possible for Jesus and his Father to, if I can put it this way, be friends. Jesus loves, worships and obeys the Father, and the Father hold him as the apple of his eye, his beloved Son, in whom he is well-pleased. He sees that this is sacrified, once we give into S-modalism, as many theologians are wont to do. Despite what the United Pentecostals say, it just won’t fly to think of this loving relationship between the Father and Son as one self, one person sort of talking to himself, patting himself on the back, as it were.

But of course, the immediate objection comes: “Duuuuude. That’s tritheism!” The rest of this post explains Swinburne’s reply. First, he’d say, oh no, my theory has one God, a collective of three divine indivduals. Second, in ruling out tritheism, the fathers were ruling out views more like classical pagan polytheisms, where the gods are truly separate, autonomous individuals, who can either cooperate or compete with and thwart each other. In my view, the Three are very tightly linked indeed.

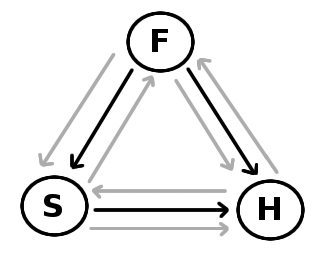

To see this, consider the above chart (made by Dale, not by Swinburne). The dark arrows represent active bringing about, and the light arrows represent passive allowing to exist. The whole entity there is God. It is in his view a “substance”, and one which is in a sense divine and personal, but it is not identical to any divine person. The persons of the Trinity are represented, obviously, by the letters in the circles. God is what he calls “ontologically necessary”. For Swinburne (this terminology is peculiar to him) an “ontologically necessary” substance is one which exists everlastingly with no active or passive cause for its existence. (1994, 465) The persons, in contrast, are each “metaphysically necessary” (again, this is his own term). A “metaphysically necessary” substance is one which is either ontologically necessary or such that it everlastingly exists, and at least the start of its existence is due to the inevitable action of some other being which is uncaused and everlasting. (1994, 146) He rejects the view, popular among theists, that a divine being must be a se (i.e. must exist through or because of itself) in the sense of ontological necessity, arguing that it is simpler and more reasonable to attribute only metaphysical necessity to them. (118-21, 170-80)

So in his view, each of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is metaphysically necessary, as the Father is the active cause of the Son, and the Father and Son together actively cause the Spirit. (He remains neutral about whether this active causation is eternal or only for the first portion of the Son’s and of the Spirit’s existence.) Each of the three, being omnipotent, must also be a permissive cause of the existence of each of the other two. In his theory the Father has a kind of priority (look at the direction of the arrows above) and this gives him authority to lay down some rules which when agreed to will prevent the wills of these three beings from ever clashing – which is important, since they’re all omnipotent. (1994, 171-5) Being perfectly good, the other can’t but agree to these policies. In sum, the Trinity is a tightly unified complex thing with three divine beings as parts, which necessarily acts much as a single personal being would. It is a whole, which is, in a sense, reducible to the sum of its parts; the entire set of truths about the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit could in principle be stated without mentioning this collective or composite which is the Trinity. (1994, 10, 13)

In sum, Swinburne is meticulously spelling out his understanding of some central elements of the tradition.

- One God? Check.

- Which is the source of everything else? Check. The three, being perfect, cooperate in all, including in the creation and governance of the cosmos.

- Generation and procession? Check. See the arrows, and his account of what those amount to – unavoidable but active bringing about.

- The Father as the “font of divinity“. Again, the arrows. Check.

- Persons which are in a sense equally divine? Check.

- Three persons “in” God? Check.

- Both God and the persons in God inevitably exist? Check.

- The persons inevitably cooperate? Check.

- Father and Son able to love one another? Check.

- Orthodox? Check.

On the face of it then, this is a remarkable success. He’s putting real meat on the bones. To mix metaphors, he’s not afraid to step up to the plate and swing at the pitches/questions you throw at him. But as we’ll see, some of the above victories may be contended.

Pingback: trinities - Swinburne’s Social Trinitarian Theory, Part 5 - Yes, we can prove it by reason alone

Comments are closed.