In the words of Moreland and Craig,

We turn finally to Trinity monotheism, which holds that while the persons of the Trinity are divine, it is the Trinity as a whole that is properly God. If this view is to be orthodox, it must hold that the Trinity alone is God and that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, while divine, are not Gods. (589, their section 3.2.2)

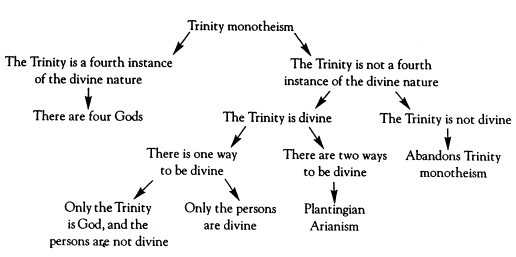

Leftow, in the essay we mentioned last time, gives a complicated objection to this whole approach, which Moreland and Craig represent in the following helpful chart. (p. 590)

Leftow’s point is that no matter how you develop Trinity monotheism, you end up with an unacceptable theory – one of the things at the bottom of the chart. So take your pick – from left to right – four gods, the persons aren’t divine (contrary to orthodoxy), the persons are divine but God ain’t (contrary to orthodoxy), or what Lefton contentiously calls “Plantingian Arianism”. (This is the social trinitarian theory propounded by theologian Cornelius Plantinga, which on Leftow’s view involves greater and lesser ways to be divine, the Father being held as the origin of the other two, and so divine in a greater sense. So it isn’t properly speaking “Arian”, but Leftow calls any theory including degrees or levels of divinity “Arian”.) Or (far right side of the chart) one can abandon Trinity monotheism.

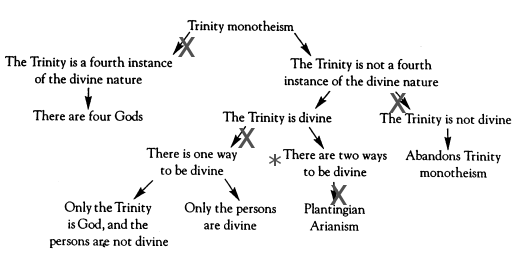

How do Moreland and Craig respond? Like this – I’ve doctored up their chart to represent their reply.

The Trinity Monotheist, they urge, should not make the inferences I put a “X” on, and should make her stand where I put the asterisk (*). In other words, Moreland and Craig want to say that there are two ways to be divine, yet this doesn’t implicate them in any objectionable “Arianism”. More on this next time.

So how do they head off the Quaternity problem? Simple. Only the Trinity is an instance of the divine nature, as the divine nature includes the property of being triune; beyond the Trinity “there are no other instances of the divine nature.” (590) So if “being divine” means “being identical with a divinity” (i.e. being a thing which instantiates the nature divinity), then none of the persons are “divine”. But they don’t put it that way. They want to say that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each “divine” in another sense, and they labor to make that clear.

Technorati Tags: William Lane Craig, JP Moreland, Trinity Monotheism, Leftow

Hi Sean,

“If Jesus be not God then worshipping him would be idolatry.” This is a serious charge. Are you aware that a number of unitarians have denied it? Also, what is your take on the scene at Revelation 5? That looks like worship with two objects of worship to me. In your view, is this an act of idolatry?

I’m very interested in this topic (monotheism, idolatry, the uniqueness of YHWH) and I’ll cover it in more depth, after I go through some more mainstream stuff.

Best,

Dale

If Jesus be not God then worshipping him would be idolatry. Jesus clearly stated who should be worshipped in John chapter 4–the Father. He specifically pointed out later that the Father is “the only true God” (John 17.3). Then after his resurrection he identified his Father and our Father as his God and our God (John 20.17). Why not just stick to this simple understanding? The Father is God. Jesus is the human Messiah. This is where the Scripture stops, with Jesus elevated (even above the angels in rank) to the highest place of authority in the universe available–the right hand of God. Why continue speculating? Why not just worship Jesus’ God.

I’d love to continue this discussion on our blog

Hi Sean,

Thanks for the comment. A standard move to your first point would be to appeal to the concept of progressive revelation. Why couldn’t the Father be revealed first, and then the other two?

I can understand your impatience with philosophical speculations! It seems to me, though, that even many anti-trinitarians are in a sense devoted to Christ as well. Some affirm that they worship both God and Christ, some say that God alone gets a “higher” kind, and some say they don’t worship Christ at all, but rather give him respect or something. The hearts of all three, in some sense, are divided. But in any case, if someone in some sense worships Christ, in your eyes is, would the Father be jealous? Why or why not?

When I read the Scriptures from beginning to end, I am struck with a simplistic Jewish monotheism founded in Deuteronomy and sharpened by Isaiah and the prophets until there is no room left for 3 in 1. In fact 2 Kings 19.19 says that Yahweh is God alone. Jesus is clearly not Yahweh because in Psalm 110.1, Yahweh addresses Jesus (David’s Lord) and in Micah 5.4 it is said that Yahweh is Jesus’ God. Why haggle over these philosophical speculations any longer? Why not free ourselves to single-hearted devotion, not to three persons but to one who alone is truly God (John 17.3).

more resources here

That’s a fair use of ‘Arian’. For all we know for sure, though, Arius was not an Arian in that sense. But that’s a dominant note in the first council of Nicaea’s anathemas, that and that the Son was created from nothing, and no doubt the council saw these as going hand in hand. And I suppose what the council says Arianism is should count for something when it comes to how we use the term.

Good point, Joseph – Leftow’s hardly the first to use “Arian” for any theory that poses ontological inequality between the persons.I guess I think that gives Arius too much credit! 🙂 I use “Arian” for people who say there was a time when the Son was not, and “subordinationist” for the generic term – such may or may not agree with that thesis about the temporal creation of the Son.

Excellent exegesis. I only want to take exception with one small point: Leftow’s ‘Plantingian Arianism’. C Plantinga Jr, following JND Kelly, in The Athanasian Creed, says that one target of the Creed is the view that there are different kinds of divine being so that when it says there aren’t three Gods it has in mind an Arian-type view that says the Persons are of different divine natures or substances: the Son’s deity is of a different kind from that of the Father’s deity. This is what Leftow describes as Plantingian Arianism. So in calling it Arian, he takes himself to be adopting Plantinga’s usage, not one of of his own invention. It is true that Leftow applies the label to some versions of Plantinga’s own ST theory. But the label doesn’t itself mean some version of Plantinga’s ST theory.

I agree that the name ‘Arian’ has come to cover a lot of different views, some of which aren’t even in the same trajectory as Arius. Rowan Williams’ Arius, RPC Hanson’s In Search of the Christian God, and Lewis Ayres’ Nicaea and its Legacy have taught us this much. I don’t think this calls for abandoning the title but it does call for caution in its use.

-Joseph Jedwab

When can we all realize this is a futile exercise?

Comments are closed.