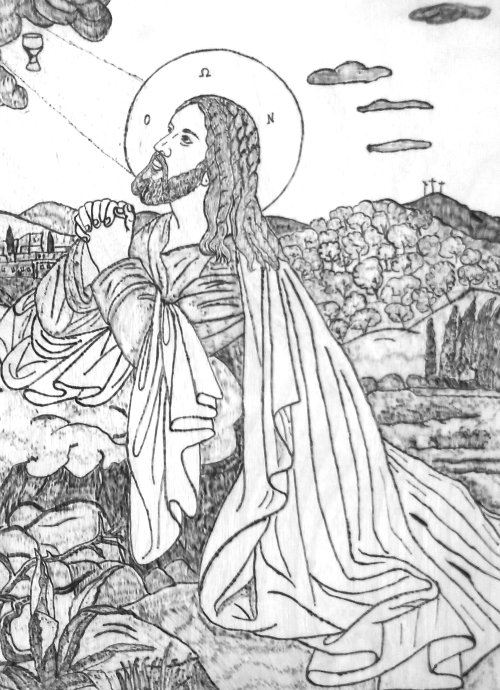

It is impossible to ignore that prominently in the New Testament, two members of the trinity/Trinity interact in I-Thou, Me-You ways, as person to person, self to self. Thus, Jesus prays to his Father, and sometimes, the Father speaks about or to Jesus. This seems to presuppose that both Father and Son are selves. And in a few passages, “the Holy Spirit” is said to speak, or to grieve – things which arguably only selves can do. (e.g. John 14:26; Ephesians 4:30; Acts 5:3, 13:2)

It is impossible to ignore that prominently in the New Testament, two members of the trinity/Trinity interact in I-Thou, Me-You ways, as person to person, self to self. Thus, Jesus prays to his Father, and sometimes, the Father speaks about or to Jesus. This seems to presuppose that both Father and Son are selves. And in a few passages, “the Holy Spirit” is said to speak, or to grieve – things which arguably only selves can do. (e.g. John 14:26; Ephesians 4:30; Acts 5:3, 13:2)

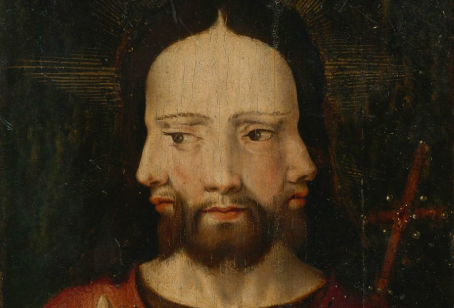

Recent “social” trinitarians of the last fifty years or so have come up with a new theme previously unheard of: the Trinty (or the trinity?) as a loving community, a happy collective of friends, eternally enjoying one another. These trinitarians are thinking of the three Persons as so many selves, that is to say, as three personal beings or persons.

This seems to accommodate the New Testament portrayals of friendship and cooperation between the “Persons,” but only at the cost of tritheism, a high price indeed. Isn’t monotheism a non-negotiable, as far as the Bible is concerned? And what has become of the idea of a tripersonal god? Is the Trinity, the triune god, a mere group of deities, or a whole composed of deities which is not it self a deity, not a god? How can the Trinity not be a god?

Against these three-self trinitarians, probably the larger group of trinitarians in recent times have asserted that the “Persons” of the Trinity are “not persons in the modern sense.” This, of course, tells us what they are not, and doesn’t tell us what they are. It can mean as little as that the three selves are not “separate from” one another, as they have perfect access to one another’s thoughts, desires, feelings, and experiences. Or it can mean that the “Persons” of the Trinity are not much like the “minds” or souls, discussed in Western philosophy since the work of Rene Descartes (1596-1650), in other words, non-physical selves.

But what else might these eternal, divine “Persons” be, if they are not selves? In general, non-social trinitarians consider them to be something less than selves, the sorts of things which might exist in, or dependent upon selves. The two most prominent 20th century trinitarian theologians, Karl Barth (1886-198) and Karl Rahner (1904-84) suggested, respectively, that “modes of being” or “manners of subsisting” might be a better term for what God is three of. Why did they say this? In short, they were concerned to keep their theology monotheistic, that is, presenting one and only one god. If the “Persons” are ways the one god is, they don’t then seem to be three gods, three divine selves. On this view, the “Persons” are not selves, but ways the one divine self is. This is one self trinitarianism, thought it is usually not called that.

But what else might these eternal, divine “Persons” be, if they are not selves? In general, non-social trinitarians consider them to be something less than selves, the sorts of things which might exist in, or dependent upon selves. The two most prominent 20th century trinitarian theologians, Karl Barth (1886-198) and Karl Rahner (1904-84) suggested, respectively, that “modes of being” or “manners of subsisting” might be a better term for what God is three of. Why did they say this? In short, they were concerned to keep their theology monotheistic, that is, presenting one and only one god. If the “Persons” are ways the one god is, they don’t then seem to be three gods, three divine selves. On this view, the “Persons” are not selves, but ways the one divine self is. This is one self trinitarianism, thought it is usually not called that.

What is a god? A divine being. What is a divine being? One popular answer is that a divine being is one who essentially has the divine attributes. What are those? According to the Bible and later Christian tradition, things like moral perfection, perfect freedom of action, unlimited knowledge, and the greatest sort of power to intentionally do things. Notice that each attribute just named seems to be the sort of feature only a self could have.

Also, take note of the way Christians relate to God. Made for fellowship with him, we have offended him, and need to be reconciled to him. We need his forgiveness, and we can talk to him. And sometimes, in dreams, visions, or through written sources, God speaks back. When he does he says, “I,” “me,” and “my” – he’s a someone, a self. And not just any old self, but a divine one, the only divine self, the only god. For Christians, “God” is not a force, a mere idea, or a something-or-other. Our “God” is a someone, to be compared to an ideal human parent, the heavenly “Father” taught by Jesus and his apostles.

We can’t, in the view of these theologians, posit three divine selves, for such would be three gods, which is two too many. Yet, catholic tradition insists that the three “Person” of the Trinity are equally divine. They must be, the thought goes, three ways that the one divine self is, three of his modes.

Lest someone howl that this is “Sabellianism,” a view attributed to the obscure third century theologian Sabellius, and repeatedly denounced since then, these modern theologians need only to add that the modes are eternally concurrent, not one-after-the-other, and that each is essential to God. Essentially, they think, God lives in these three ways that we call “Father,” “Son,” and “Holy Spirit.” Just what this amounts to is variously explained. Sometimes these are compared to personalities or personas which may be multiple within a human person. But in any case, in their view we have one divine self who lives his life as three “Persons,” and so we have precisely one god, God.

But what, we wonder, happened to that prominent New Testament theme mentioned above, the interpersonal relationship between Father and Son? Can this be understood as a friendship (or “friendship”) between two modes of one divine self? Was the man Jesus a “mode” of the one God, and not a being in his own right, a human self, which is to say, a living human being?

Who is right? It looks to be a tough dilemma. Either you give up real interpersonal friendship between the “Persons,” or you compromise monotheism, with three “fully divine” selves, each seemingly a god.

Might there by another way? Should we decline to say either that God is more than one self, or that God is one self? Is this a position we can actually believe and practice? Some, loving paradoxes, may affirm both exactly one and three, but that looks like trying to paint a happy face on what we’d consider a theoretical failure in any other area. It is no achievement to assert that God is and is not a (single) self.

Might there by another way? Should we decline to say either that God is more than one self, or that God is one self? Is this a position we can actually believe and practice? Some, loving paradoxes, may affirm both exactly one and three, but that looks like trying to paint a happy face on what we’d consider a theoretical failure in any other area. It is no achievement to assert that God is and is not a (single) self.

These sorts of problems are widely avoided in recent academic theology. Unable to pick, many theologians self-comfort with the falsehood that these differences are merely differences of emphasis. There are, of course, differences of emphasis between various trinitarian theologians, but there are also substantial disagreements, as we’ve seen, on this core issue of interpretation. And it is a pressing issue. And a main device to put these disagreements out of one’s mind is to talk loudly and often about “the” doctrine of the Trinity, as something agreed on by all Christians, or nearly so. But the reality is more complex, and it is simple logic that if the Trinity is either a self or not. And it as simple logic that these can’t both be true: there’s exactly one divine self, and there are exactly three divine selves.

Until we decide what is meant by “Person” in the statement that “God is three Persons” we’ll be unable to even try to hunt for reasons for or against the claim, or to decide whether the claim fits or misfits the Bible. One can’t even agree or disagree with an uninterpreted sentence. You may find such a sentence in your church’s or denomination’s creed, something like

The eternal triune God reveals Himself to us as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with distinct personal attributes, but without division of nature, essence, or being. (The [Southern] Baptist Faith and Message, section II)

“Himself.” So, the triune god is a self. But so, it would seem, are the three who each enjoy “personal attributes.” Are there four divine selves here? Or do the three turn out to be ways the one divine self is? Or, despite the capitalized pronoun, is the triune god really not a self, but rather a group, community, or collective of selves? Are we to flee here to contradictions or obfuscation? The statement is wholly indeterminate. It preserves traditional catholic language which is vague enough to generate an unruly mob of clashing interpretations.

To their credit, analytic theologians (theologians trained in or at least adept in the methods of recent analytic philosophy) do recognize that there is a real, substantial disagreement here. But no consensus has yet been reached. Some think a wrong turn was taken, and that the catholic language just needs to be set aside. After all, Christianity seemed to do rather well before the fourth century. It has in various ways flourished since then, but one must ask whether this is because of widely agreed catholic formulas, or despite them.

Hi Dale,

IMO, the logical problems inherent in the LT and ST formulations of Trinitarian thought are removed if one has a correct understanding of the so-called ‘Cappadocian settlement’ [i.e. ??? ?????, ????? ?????????? = one essence, three subsistences (persons in a sense stronger than ????????)].

For a correct understanding of the ‘Cappadocian settlement’, one must add to the ‘equation’ the ???????? of God the Father, with ???????? being used in the sense that God the Father alone is the sole/single – principle/origin/source of everything that exists, including the Son and the Holy Spirit.

To avoid the charge of ‘Arianism’, the ‘Cappadocian settlement’ includes the teaching that Father communicates His essence in its fulness to both the Son and the HS.

So, addition to Arianism, the above formulations also the avoid Sabellianism and Tritheism, thus eliminating the two major problems of LT and ST.

Grace and peace,

David

David

Isn’t this just a form of modalism?? The monarch has simply manifested and personalized some of his own essence? Is a person using his essence to create a personalized aspect of his own essence really simply creating an alter ego to Himself?

This is such a goofy concept – when looked at Biblically – which sees nothing of this model. This model is simply human reasoning/assumption with no sound, comprehensive Biblical formulation. What value is it then?

When I looked at it I thought it was far from modalism. I thought he meant the Son and Spirit to be entities/beings in their own right, not mere modes of such.

the teaching that Father communicates His essence in its fulness to both the Son and the HS.

I am working from this statement – which does not sound as if the S, HS dis-tend to a point of separate (think of cellular division) – but merely are pieces of the one divine entity that the one center has chosen to personalize (a neat trick indeed!). The relationship with Modalism is that the secondary persons are really emanations of the primary persons so, while I grant they are not the SAME person (pure modalism) they are not really separate and distinct persons in the sense of pure trinitarianism 9as I understand it). Admittedly, I remain loss as to the modalist’s sleight of hand of having the human nature of the son being inhabited by the Father but separate enough to pray to Him… They have not been able to answer that either…:-).

Hi Greg,

Yesterday, you posted:

>>Isn’t this just a form of modalism?? The monarch has simply manifested and

personalized some of his own essence? Is a person using his essence to create a

personalized aspect of his own essence really simply creating an alter ego to Himself?>>

Definitely not “a form of modalism”. The “one God the Father”, truly begets “the Son of God”. It is “the Son of God” who “for our salvation, came down from heaven” and became incarnate (as per Phil. 2:6-9).

>>This is such a goofy concept – when looked at Biblically – which sees nothing of this model. This model is simply human reasoning/assumption with no sound, comprehensive Biblical formulation. What value is it then?>>

I disagree, the Bible teaches us that “the one God” is the Father, and that this “one God” has an “only-begotten Son”, who is His Word; and this Word “is God”.

I have dealt at length on these issues over at Articuli Fidei, especially under the Label Monarchy of God the Father.

[BTW, are you the same Greg Logan who attended some of the Northwest Bible

Conferences back in the 90s ???.]

Grace and peace,

David

Hey David – I am certain I THE GREG LOGAN – and it would likely have been in the early ’90s. I hailed from CCBTC – though out by that time. CCBTC was originally modalist when I arrived but became Biblical Unitarian by the time I left (albeit sometime after I had done so…:-) since it is the only logical step!).

The reason I see a conceptual modalism here is because the one BIG God person is just taking a piece of Himself and personalizing it – and sticking it into an impersonal human nature. Pure Modalism seems to maintain the same personality – but real Modalism tends to waffle around quite a bit at this point.

In contrast – the Trin has fully formed, unique, independent, persons – rather than a little hand-puppet person…:-)

BTW – I remain a staunch Biblical Unitarian – thinking the whole incarnational thing is the most bizarre, twisted, anti-Christ scheme Satan ever cooked up… I mean why not just attend Mass if you want to eat the physical body and blood of Jesus…. 🙂

Hi David,

If I understand you, you’re suggesting a view on which the one God is the Father, not the Trinity. On the view you suggest, the Trinity is not a god at all, or any sort of being – what you’re suggesting is a trinity of God, and then two which have eternally received a lesser sort of divinity from him. To me, this is obviously a form of subordinationist unitarianism, not trinitarianism. I don’t see what you’re describing as the dominant post-Constantinople catholic view, though it may indeed be the view of some of the partisan Nicenes leading up to 381. It’s just, you’ve left out the crucial claim, implied by the 381 creed, that the three of them are the same god. What you describe leaves open the view that the one God eternally causes two lesser gods.

About communicating “his essence in its fullness” – it’s essential to God that he doesn’t exist because of another, right? Well, you in principle can’t give that property to another. Right? If so, the position is subordinationist, though not “Arian.”

Hello again Dale,

Thanks much for responding; earlier today, you wrote:

>>If I understand you, you’re suggesting a view on which the one God is the Father, not the Trinity.>>

That is correct, and it is a position held by a number of modern theologians (especially of the Eastern Orthodox persuasion).

>>On the view you suggest, the Trinity is not a god at all, or any sort of being – what you’re suggesting is a trinity of God, and then two which have eternally received a lesser sort of divinity from him.>>

The issue is not one of essence, but rather pertains to etiology. As such, the divinity communicated by the Father to the Son and the HS is not “a lesser sort of divinity from him”. By way of illustration, Adam, the first human, was directly created by God. The humanity of all his descendents is not a lesser sort of humanity, yet Adam remains unique.

>>To me, this is obviously a form of subordinationist unitarianism, not trinitarianism. I don’t see what you’re describing as the dominant post-Constantinople catholic view, though it may indeed be the view of some of the partisan Nicenes leading up to 381.>>

IMO, the term “God” is used in two different senses in the Nicene and Nicene Constantinopolitan Creeds. First, as a description/title of “the one God, the Father”; and second, as the equivalent divinity proper, “Light from Light, true God from True God”.

>>It’s just, you’ve left out the crucial claim, implied by the 381 creed, that the three of them are the same god. What you describe leaves open the view that the one God eternally causes two lesser gods.>>

If the Father is in fact is “the one God”, “the one God” who begets “the Son of God”, then I would argue that there is a concrete sense in which the Son of God is NOT “the one God”.

>>About communicating “his essence in its fullness” – it’s essential to God that he doesn’t exist because of another, right?>>

Essential to “the one God” of the early Creeds and the Bible.

>>Well, you in principle can’t give that property to another. Right?>>

Correct, the Father owes His existence to nothing/ no one; He and He alone is autotheos.

>>If so, the position is subordinationist, though not “Arian.”>>

Correct, but, once again only as it concerns etiology.For more in depth reflections on these issues, see the following threads:

Is ‘the one God’ of the Bible the Trinity, or God the Father

Dr. Sam Waldron on the Monarchy of God

The Monarchy of God the Father and the Trinity

Grace and peace,

David

Comments are closed.