Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | Email | RSS

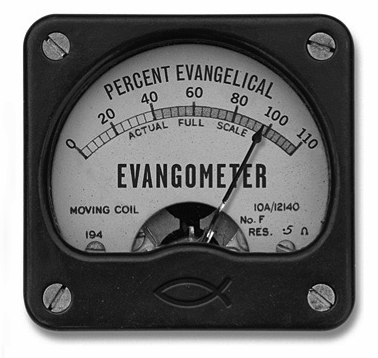

According to recent research, about 3 in 10 Americans are evangelical Christians. But what exactly is an evangelical? A fairly standard definition is given by historian David Bebbington. In his view, an evangelical is someone with the following four beliefs:

According to recent research, about 3 in 10 Americans are evangelical Christians. But what exactly is an evangelical? A fairly standard definition is given by historian David Bebbington. In his view, an evangelical is someone with the following four beliefs:

- Conversionism: the belief that lives need to be transformed through a “born-again” experience and a life long process of following Jesus.

- Activism: the expression and demonstration of the gospel in missionary and social reform efforts

- Biblicism: a high regard for and obedience to the Bible as the ultimate authority

- Crucicentrism: a stress on the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross as making possible the redemption of humanity

And here is the recent, revised four points used in research by the National Association of Evangelicals and LifeWay Research, according to which anyone who strongly affirms all four counts as an evangelical:

- The Bible is the highest authority for what I believe.

- It is very important for me personally to encourage non-Christians to trust Jesus Christ as their Savior.

- Jesus Christ’s death on the cross is the only sacrifice that could remove the penalty of my sin.

- Only those who trust in Jesus Christ alone as their Savior receive God’s free gift of eternal salvation

It is frequently asserted by some theologians that the Trinity is the most central Christian and evangelical belief. But belief the Trinity usually isn’t given as a defining belief on an evangelical. However, the NAE on their website mentions the Trinity as if it were an essential belief; they appear to be assuming that trinitarian belief is obviously entailed by commitment to the Bible.

As we discuss, in the evangelical churches attended by Mr. Zarley, the traditional catholic Trinity and two natures doctrines were strongly emphasized. But in the evangelical churches I’ve attended, these were very much on the back burner – on the books, but not a central part of our belief or practice, and the ancient catholic formulations were nearly always ignored. We were functionally non-trinitarian, but officially trinitarian. Yet all these churches were firmly in the evangelical world. Mr. Zarley and I agree that an evangelical is not by definition a trinitarian.

Do you agree? Let us know what you think in the comments below, in our Facebook group, upload audio feedback for possible inclusion in a future episode of this podcast, putting the audio file here.

You can also listen to this episode on Stitcher or iTunes (please subscribe, rate, and review us in either or both – directions here). It is also available on YouTube (you can subscribe here). You can support the trinities podcast by ordering anything through Amazon.com after clicking through one of our links. We get a small % of your purchase, even though your price is not increased. (If you see “trinities” in you url while at Amazon, then we’ll get it.)

Links for this episode:

- Kermit Zarley home page

- podcast 86 – Kermit Zarley on distinguishing Jesus and God

- podcast 87 – Kermit Zarley on the deity and preexistence of Jesus

- NAE’s “What is an evangelical?”

- Wheaton College’s “Defining Evangelicalism”

- LifeWay’s recent research announcement

- Mark 13:32; Matthew 23:36

- How Trinity theories conflict with the New Testament

- podcast 29 – Arius

- podcast 30 – The Council of Nicea

- podcast 31 – Dr. William Hasker on the “Arian” Controversy

- The Lost Early History of Unitarian Christian Theology

- traditional Catholic and Protestant views on whether any non-Christians can be saved

- James 2:14-26

- 1 Corinthians 3:1-17

- This week’s thinking music is “Doria” by Robert Anthony Ruzzo.

I think that the definition of evangelical given was not meant to be a total definition over against all other perspectives but rather one which operates over against what evangelicals would see as being a broader category of Christianity which they would define to include mainline Protestants and possibly Roman Catholics and Orthodox, all of whom are trinitarian. Evangelicals tend to see themselves at the “good guys” of the larger Christian crowd and I think their emphasis in those several points of self definition reflect that.

I think that particularly the emphasis on conversion and being born again leads to a culture and belief system which is self perpetuated on the back of what evangelicals call “testimony”. This forms a very experiential epistemology for them and thus they are not very prone to questioning their core doctrines, such as the trinity, or their unique understanding of salvation. The group self perpetuates and loyalty to the group and the group beliefs seem to be strong amongst evangelicals. Their faith is based on experience, not the Scriptures, and they have years invested in their testimony. Their own perspective on their journey is sadly often mistaken for God’s voice.

For those of us who are former evangelicals, it’s understandable to look back and relate to those from our past and try to reach out to them. Our experiences and story define us in unique ways based on where we came from. I think the Apostle Paul in Rom. 9 is experiencing that same thing in his deep love for his brothers the Jews. Yet Paul was called to be an Apostle to the Gentiles and those of us who are rejecting evangelical doctrines should not be afraid to examine other doctrines besides the one or two we have yet discovered they are mistaken about.

For rejecting any major belief of a religious group such as evangelicalism forms a slipper slope, and evangelicals realize this. Once one admits that the group is wrong about something major, pandora’s box has been opened. In my own case I have no interest in identifying with evangelicalism because my journey of faith and study of the Scripture has lead me away from many of their major doctrines until I am now feeling that they make themselves enemies of much of what the Scriptures do teach and emphasize.

In my case I am a heretic by evangelical standards 5 times over. I am Biblical Unitarian and that the Father is God, Jesus being His Son. I believe that final judgment/resurrection/eternal destiny is based on deeds. I believe that righteousness is a real moral quality reflected inwardly and outwardly in a person’s life. I believe the cross saves us only as we identify ourselves with it in taking up our crosses to follow the Messiah as our example in living a life of righteousness, empowered by God’s Spirit. I believe the gospel is largely about the coming kingdom of God to earth, and our preparation to live in it and call people into it. I believe in conditional immortality. I have an extremely weak/nonexistent view of original sin, and I also completely reject the concept of imputed righteousness as being an oxymoron. For all the reasons and more, from an evangelical perspective, I am a heretic, and could in no sense be considered by them to be a Christian. The slope is slippery and I understand where they are coming from because in being formerly one of them, I was taught to think in this way. But if you ask the Bible to provide your theology for you, you will go in a different direction than evangelicals have.

Yet on the positive side, I believe in God the Father, that Jesus is the Messiah, that He was born of a virgin and that He lived among us in the flesh, was crucified for our sins and rose on the 3rd day, that He ascended to heaven and will return for His people. So I call myself a “Primitive Christian” so that people will understand that I keep to the basics and don’t agree with the developments.

It’s natural to look back but I think it’s also profitable to look forward. Rome never admitted that Luther was right and evangelicals would never admit that Biblical Unitarians are right. Powerful cultures never let go of their control.

I am not an evangelical – and despise the term – and the leadership for the most part.

Much is made of the lack of reference to the Trinity in the Bebbington description of evangelicalism. At the same time, I don’t see a reference to the resurrection of Christ in his definition either. Indeed, I would think it rather difficult to find someone who today accepts the moniker of “evangelical”, as currently understood, while denying the literality of the resurrection. On the other hand, I think mainstream evangelical folks would argue that, while admitting that unitarians may fit within the bounds of the Bebbington construction in a narrow sense, evangelicalism as a movement arose predominantly out of a Protestant confessional orthodoxy that was trinitarian.

Dale & Kermit,

Good discussion. I’ve also attended and served in ministry at Evangelical churches (even though I don’t believe in the Trinity doctrine). The pastors respect my academic credentials and I’ve learned not to challenge them (publically) or cause any trouble.

I just finished reading Zarley’s “Samaritan Riddle” book.

Comments are closed.